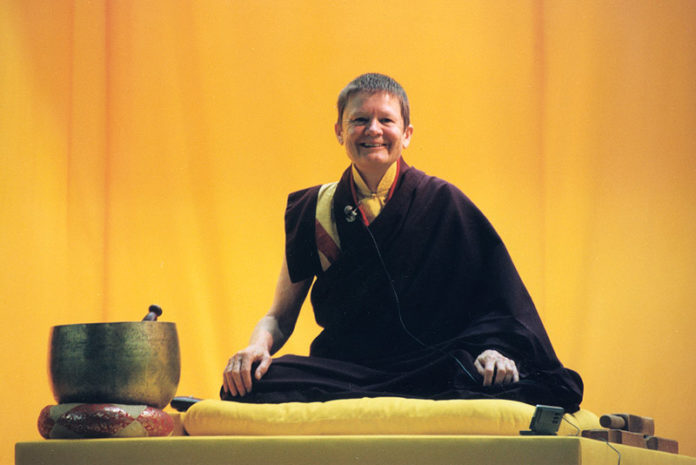

In part one, How I met Rinpoche, Pema describes her first encounters with Trungpa Rinpoche. Here Pema talks about the experience of being his student, what she learned from him directly and indirectly about being a nun, and the specific instructions Rinpoche gave her about monastic discipline at Gampo Abbey. The following conversation took place in Halifax on 10 December 2003.

Pema Chödrön: After I met Rinpoche and had that first interview, I went off to this Sufi camp in the French Alps and met Lama Chime, started to study with him in England and then eventually came back to the United States.

Walter Fordham: He was at a Sufi camp?

Pema Chödrön. The Sufi camp was run by Pir Vilayat Khan and literally every week someone from a different tradition came, so this was the buddhist week. By the time I went back and formally asked Rinpoche if he would be my teacher, I was a nun. I moved to San Francisco because I have children who were then teenagers who were living there with their father. I eventually moved into the San Francisco Dharmadhatu. Rinpoche came and gave the opening talk for the Dharmadhatu. After the talk he went upstairs and I literally ran and sat on the couch next to him and asked if I could be his student and he said yes. It’s pretty simple, you know….

WF: And were you wearing nun’s robes?

PC: Yes.

WF: And did he say anything about that?

PC: So this is very interesting, right? You might think that somehow he would try to convince me to give back my robes or something like that. Not at all. He must have felt it was right for me, which indeed it has been really right for me. But from the beginning he was very strict with me and he always told me to keep the vows properly. No fooling around with it. There’s lots of stories of course but maybe the nun angle is interesting?

WF: Well that is an interesting angle—the way that Rinpoche related to you as a monastic. That’s something that very few of his western students experienced.

PC: It was interesting, I became Rinpoche’s student, moved to Boulder and so forth, and I went to many of the seminaries a lot to help with practice. But I always longed to spend more time at the Court. I wanted to be closer to Rinpoche. I think in my mind I wanted to get as close, as I could, so that if there was anything that was going to bother me, I would see it firsthand. From a distance there were things about Rinpoche that seemed challenging. So, I just wanted to get as close as I could. That turned out to be very wise. That’s how my devotion grew. The closer I got, the more I loved him. Once, I think it was Beverley who said, “If you want to go over there you just have to ask.” So I did.

One time at a seminary I was living right downstairs from his suite, so I asked if I could have dinner or something and always, whenever I asked (and I had to ask every time), I was invited. But I remember that particular dinner because wine was being served and Rinpoche said I should have some wine and then he said, we have to do the consecration of the wine in order for you to be able to drink it.

PC: But he rarely called me on anything. He let me find things out for myself. I remember a wedding at the Berkeley Dharmadhatu. I went to the reception and there was dancing and I had been a nun….I don’t know….not that long, maybe two years or something. Rinpoche was there watching everyone dancing and it was rock-and-roll dancing, and I was dancing along with everyone else. Then I went to the bathroom to pee and there was a woman in there who said to me, in a very sweet way, not a disapproving way, “I didn’t know nuns were allowed to dance.” And it just hit me, I suddenly had this picture of myself in robes out there doing rock and roll and I thought “It’s really off” and I never danced again. But he never said a word to me about it.

But there were certain times….like one time at an assembly. It was really hot and I was sitting in the front row with Ane Palmo and Anne Stevens who at that time was Ane Yeshe. Because it was so hot we had our outer robes, down around our waists instead of, you know, wrapped around our shoulders and torsos. Rinpoche sat down, looked right at me and he went like this. He made this gesture like, put on your robes! And the three of us—Bong! We put on our robes. And then after that, I didn’t care what the weather was, I always wore it properly.

When the Sixteenth Karmapa died there was a big ceremony at Dorje Dzong in Boulder. Before the ceremony, while everyone was busy getting ready, Rinpoche sent word to Marpa House, asking me to come to the Court to help Taggie [Trungpa Rinpoche’s son] get dressed in his robes. Since that time I have done many ordination ceremonies and helped lots of people with their robes. But this was the first time that I helped anyone put on their robes. So I went to the Court and started to help Tagi and it just wasn’t working. Tagi was standing still, so it wasn’t that he was wiggling around or anything, but I had a hard time figuring out how to do it. Fortunately Rinpoche was sitting there watching me and that’s when he taught me how to wear my robes properly. I don’t know how familiar you are with the robes but there’s a lower robe and an upper robe and you wear a shirt, usually sleeveless, but there’s also a vest that you can wear. So Rinpoche gave me a lesson on how to dress in traditional Tibetan monastic robes. First he asked me to take off the lower robe (and of course you wear a long skirt underneath so this was not an immodest situation) and he showed me the right way to put it on. He showed me how to fold it a certain way and how to make the pleat in front and the other pleat. I was also wearing a brocade vest that had been copied from his monastic vest. He had loaned it to me to copy, but I was wearing the vest without a belt. He told me that usually, when you wear the vest, you also wear a belt that goes with it. There was a red satin ribbon on the table next to me. He picked it up and gave it to me to use as a belt for my vest. I still have that red satin ribbon. It’s pretty shredded now and I keep it in my reliquary, but I wore it for years.

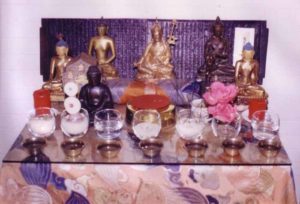

Eventually I got the job of taking care of the shrines at the Court, the Buddhist shrine and the Shambhala shrine on the main floor, and his personal shrine upstairs in his sitting room. Once he spent a whole morning showing me everything that was on the shrines, all the rupas and offerings, and he showed me how to clean them.

WF: Can you go into any detail on the care of the shrines? What he told you?

PC: Yes. Because I’ve actually shared this with quite a few people since. Well, the first thing was that once a week I should take everything off of the shrines. Then I should polish the glass but I shouldn’t just use any old cloth, I should have special cloths for doing this. Then I should clean everything that goes on the shrine, like all the statues and everything and I should have special cloths for those. I remember going out and getting these special cloths and I kept them at the Court in a box that said “Do not use for anything else.” He said all the glass shrine bowls should be cleaned until they sparkled. Then he took me to the kitchen and he showed me how to clean his upstairs shrine bowls, which were silver. He cleaned them with [in a whisper] Ajax. Do your remember that?

WF: I do, yeah.

PC: He liked the dull finish and so they were cleaned with Ajax . He also showed me how to handle the statues: with two hands, lifting from the bottom, you could hold it from the back, but you should never touch the head. He was very meticulous and detailed and patient showing me all these things, and I so appreciate it, you know. Cleaning the shrines got me to the Court every week and up in his sitting room next to his bedroom where he would often be sleeping while I worked.

I remember being invited once to a Translation Committee meeting in that upstairs sitting room. They were translating the vinaya texts for the confession liturgy that we do every full and new moon at the monastery. It’s called Sojong [Poshadha in Sanskrit]. What I remember is that Rinpoche was so happy to be doing that translation. He said it was like a dream come true that we were actually doing this translation and making it available to people.

Another time he told me that we should carry special cards that showed we were Gampo Abbey monks and nuns. We also haven’t done that. We should.

WF: A card? Like a business card?

PC: Yeah like a business card, I guess. But maybe laminated, you know.

WF: What other things did he tell you?

PC: One thing I always remember; he would stop every so often when I was in a crowd of people-you know once a year, twice a year, but out of the blue, unexpectedly—and say, “Don’t be too religious.”

WF: Always the same message?

PC: Always the same message. “Don’t be too religious.” And of course I’d get paranoid, “I’m being too religious?” But it was just basically a message about how to proceed. Don’t be too religious. So I certainly always remember that. And the other thing was when Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was about 18 or so, I’m not sure. When he started his prostrations….

WF: I think he was a bit younger. He might have been 16.

PC: Anyway Rinpoche asked me to be the Sakyong’s meditation instructor for ngöndro. I would come to the Court for that and whenever I was there with the Sakyong (he was called the Sawang at that time) Rinpoche would stop and say, “Don’t make him into a monk. I have other plans for him.” That was another message that he repeated. But he didn’t say it as often as the other one, “Don’t be too religious.”

You know I started getting sick in Boulder with chronic fatigue. But no one had a name for it in those days. I had it in my mind that if I could get to Nova Scotia, my health would improve. I kept asking Rinpoche if I could go and he kept saying no. It was very interesting, he said you cannot go until you learn about politics. And I remember thinking: Now how am I going to….? What does he mean, learn about politics? So I asked permission to attend all the Vajradhatu board meetings as an observer and they let me do that. It was a smart move. Just watching those guys working things out around the table, and realizing there was no one to lobby because there was no one in charge exactly. So I learned about politics. I really did.

WF: That probably came in handy once you were at the monastery.

PC: Really handy. At some point, I got the message, that I should go to Nova Scotia and I should go soon. I was overjoyed. I went straight up to the Abbey, and it was awful. Boy it was so rough in the beginning. It was unbelievably rough.

But let me back up for a minute. Before that, during (I think) the 1982 Seminary, I put in a request through Beverley: Could I see Rinpoche to just talk about the monastery? And that afternoon, I got a message that I should come then, which was pretty unusual. I had been to quite a few meetings with Rinpoche and they had always been in a living room or a sitting room with Rinpoche sitting in his chair and I’d be sitting on the couch or something, usually discussing practice and study issues or whatever. So I arrived expecting it would be like that, but instead I was ushered into the bedroom. All the curtains were drawn and Rinpoche was sitting on the bed. I said something like, “This is a really odd environment for having our discussion about the monastery.” He didn’t crack a smile. He was dead serious. He beckoned for me to come over and sit on the floor next to the bed and then he told me several important things. I don’t think I asked any questions, he was just telling me these things that he wanted me to know.

He said, “You know everyone’s watching you, all the Tibetans are watching you. They’re watching how you wear your robes, they’re watching how you move, they’re watching how you talk to people, so do a good job.”

He told me that one of my main jobs would be to sort out people’s motivation. He said a lot of people are going to want to become monks and nuns because they can’t get it up—their romantic thing didn’t work out and they decide to take vows. He said that’s not good motivation, monastic life shouldn’t be an escape. That’s when he made the famous comment which I’ve repeated many times: “The monks and nuns should always be horny.” He said, “We want real energetic juicy monks and nuns but they should keep their vows impeccably.” He said that we needed Shambhalian monks and nuns. I didn’t think to ask him exactly what he meant. But I took it to mean: looking good and comporting ourselves well.

At some point I asked, “Do you have any kind of vision for the Abbey?” And he said it’s better not to have too much vision of exactly how you want things to be. He said, “My advice is make small moves and see how it evolves.”

He also said, “I want the Abbey to be a very strict place with good discipline and I’m going to ask Thrangu Rinpoche to be the abbot.” By that time I think it already had the name, Gampo Abbey. Tsultrim had already been in Nova Scotia and had started Gampo Abbey number one in a little house in Maitland. I don’t know if you know about that.

WF: No I don’t.

PC: It was definitely not an abbey. It was just a house. But Tsultrim and Steve Brooks looked at several properties and each time Rinpoche rejected them. Then the next year they looked again and they found the land in Cape Breton where the Abbey is now and Rinpoche liked the photograph. I know because I was there when he got it. And then he went up there and he said, yes, we should take this property.

WF: What did he say about it?

PC: I wasn’t there, but I’ve heard about it. He sat in the room where he was staying and just looked out the window all day and at some point he walked around the grounds with Mitchell. There are some photographs of that. He said, “Yes we should get this place.” He indicated that the only problem might be that the monks and nuns would levitate because it was such a spectacular kind of view and I often thought about that. Was he making a joke? Now things are so good there, but for such a long time it was so rough and so hard and everyone was always at each other’s throats. It was really terrible for a long time and the early days were the worst.

WF: So it’s getting late, I should let you go?

PC: I think so and then we could talk another time.

WF: Thank you so very much for this Pema.