Here—three years shy of Boston’s fiftieth anniversary—are excerpts from Anna’s original article. This portrait of the first tentative steps and missteps of the Boston sangha is worth a fresh look, in part because it is funny, tender, and insightful. But this piece also provides a very interesting glimpse into how we viewed our baby steps so soon after they were taken, and how quickly Trungpa Rinpoche’s mandala became more or less fully manifest. By 1979, Vajradhatu, Shambhala Training, the Kalapa Court, Naropa, the Kasung, and much more had been established and—if not yet fully matured—were distinct and formidable landmarks of the mandala.

I remember in early 1974 being first told about the practice of prostrations and thinking it was a joke in very poor taste. Now [1979], new people come to the Boston Dharmadhatu, to our loft in the center of town, where Shambhala Training is carried out by friendly and efficient crews, where regular daily and all-day weekend sittings are open to the public, where two or three classes are held simultaneously most evenings, where pretty elegant receptions are periodically staged with a fair amount of aplomb, including occasional grand visitations from Rinpoche and the Regent, where ngöndro and Vajrayogini sadhana are practiced, and the new people seem to accept it all quite easily. I suspect they can live with all this mostly because of Rinpoche’s inspiration and perseverance—slowly ploughing, aerating and fertilizing the ground for years; partly also because people in general are much more sophisticated about practice today; but in small part, too, because we, the Buddhist neanderthals, died on a strange and wonderful assortment of crosses for them over the past seven years (which may be the same thing as saying that we were some of that hard, rocky ground that was ploughed).

The Boston Dharmadhatu started in 1972 with Patricia Shelton’s hatha yoga group, which met at her East-West Center. We were followers of Rudrananda, Muktananda, Vankatesananda, Vishnudevananda, Satchitananda, Ram Dass and the American Dream. The first official meetings were held at Persis McMillen’s estate in Concord, with Beth Gordon as coordinator. Rinpoche gave a talk there on The Way of the Buddha, which is in the Myth of Freedom. Narayana (later the Regent Osel Tendzin) and Olive Colon gave meditation instruction under a tree and we sat in a little outlying cottage and did walking meditation in the fields. Then we got a small loft on Charles Street, in Beacon Hill. There were 12-15 members and we met on Monday nights. On Wednesdays, we had open house—40 minutes of sitting and listening to a tape by Rinpoche. Every other Sunday, there was a nyinthun attended by four or five people.

Sitting style tended to extremes: some people sat propped up against the pillars and walls, some were prone, and some sat in the rigor mortis of full lotus (occasionally picking their toes). Walking meditation was a time for virtuoso performances, a la Jacques Tattit and the Lippizaner Stallions. Every now and then, one of the capricious Olympians from the hills of Vermont would come down and talk about pain. It was considered an art form and they were its chief exponents. Outbursts of anger, rudeness and fits of depression were considered signs of a serious practitioner. Politeness, friendliness and tidiness were considered middle-class cop-outs. In the next two years, some of us proceeded, with startling abandon, to jettison middle-class respectability and security in the form of non-meditating husbands and wives, sports cars, furniture, jobs, girdles, bras, ties, soap and razors. Some of us gave up teetotalling and vegeterianism, some of us gave up drugs (pot in particular—the only thing Rinpoche actually asked us to give up). We exchanged them for booze, sex, cynicism and the glimmer of some distant light.

Rinpoche would come to give talks and seminars Transcending Self-Indulgence, Is Meditation Therapy?, Open Secret of Enlightenment, The Intelligence of Confusion, etc. He didn’t wear a beard, long hair, flowing whites or beads. He didn’t chant into the microphone with closed eyes. His eyes were always open and he was always late, he wore suits, his hair was short, he smoked and he drank in public and, it was rumored, he had relations with some of his female students.

Some of us were shocked and relieved at the upfront quality of his behavior. Some of us were just shocked and never got beyond that. Some of us listened to his talks and they were like swallowing timed capsules—timed to go off months and years and perhaps decades later. It was like hearing extraordinary poetry—a lot of it was totally obscure, but there was something evocative, something haunting that kept us coming back. And so the culture implanted in us by Rinpoche began to ferment slowly, in the heat of our muddled practice. We began to experience learning not as acquiring, but as undoing, being undone.

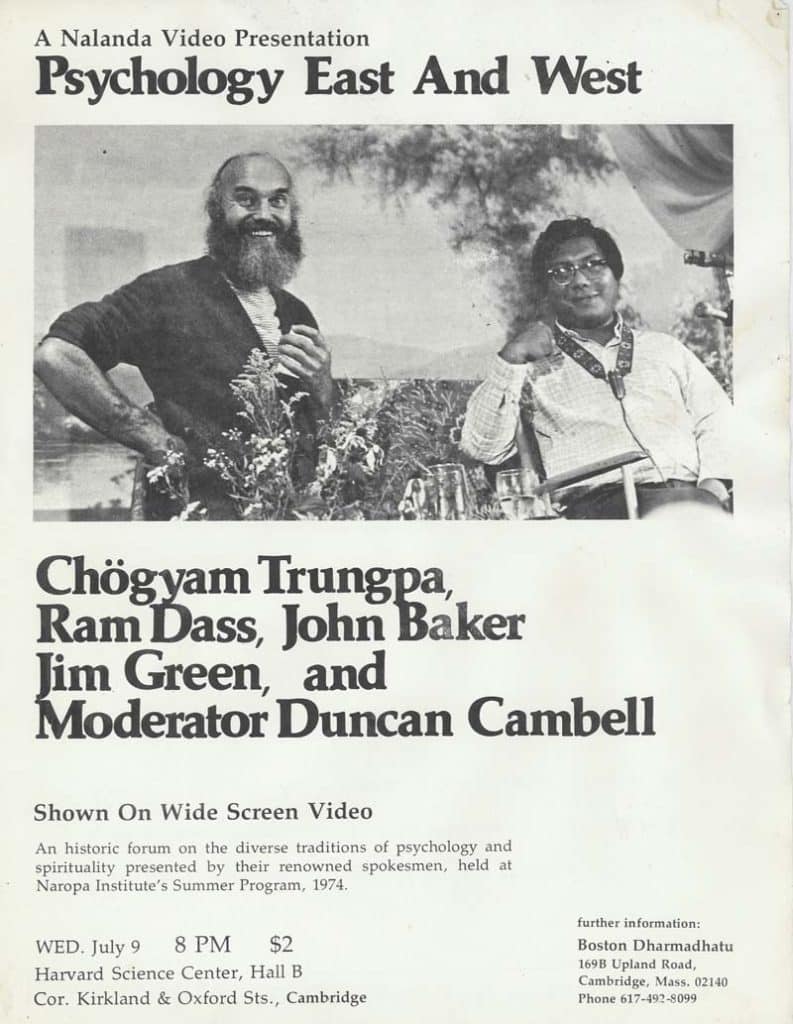

From time to time, Karl Springer would appear amongst us. He was learning to be Sol Hurok (an early twentieth century music agent and impresario) at the time, and went in for festivals. His education proved somewhat expensive to the rest of us, but definitely broadened our horizons. There were two festivals: the Dharma Festival in 1973 and the Mandala Festival in 1975.

The Dharma Festival brought us into uneasy partnership with the followers of Ram Dass. We Buddhists tended to be small, nervous, alcoholic, and we travelled in clouds of smoke. The dasses tended to be tall, handsome, vegetarian and they moved in an aura of mint tea. They lived on Washington Road, in a Victorian mansion owned by professor David McClelland, a sort of Harvard Don Quixote of the counterculture. We lived two blocks away in a large house on Upland Road. They would sneak over to our house at night for alcohol and protein binges, resorting secretly to cow flesh and woman flesh on our premises. They thought of us as arrogant debauchees and we thought of them as holy noodles. There was a grain of ugly truth on each side.

Ram Dass drew 3,000 people to a talk and slide show called, Gurus of the Ages. Allen Ginsberg and Bhagavan Dass sang, Keep on truckin’ down the eightfold path. Rinpoche talked to a crowd of 1,200 people at Rindge Auditorium on Tibetan Buddhism and American Karma. He talked about the validity of our glimpses into the teachings, our enormous good fortune at having this opportunity to practice and the need for more discipline. He was very moved and so were we.

The Mandala Festival was a totally Buddhist effort. We mounted an exhibition of Tibetan art at MIT (which resulted in the publication of Visual Dharma by Rinpoche, based on his lecture); there was a folk concert and a Peter Serkin concert, a poetry reading, lectures and a panel discussion between Rinpoche, Eido Roshi, an eloquent Episcopal father and a dapper rabbi, chaired by the ubiquitous Harvey Cox; it also snowed most of the time even though it was April and we lost $10,000.

Festivals and houses were our specialty in Boston. The original idea of getting a house was Alan Sterman’s, who soon after thought better of it and went “Outward Bound”. The rest of us found ourselves just bound, panicky, fighting assorted windmills and ourselves.

In looking for a house, we divided into two camps—those in favor of hippy funk and those in favor of uptight Zen. The uptight Zen won and we rented 169 Upland, in Cambridge, at twice the amount we had expected to pay. Before we even moved in, we clashed over the issue of whether or not to admit dogs and non-meditating husbands (I had one of the latter, for a while).

The political system was one of rampant democracy: part town meeting, part encounter group. Dharmadhatu business and house business were discussed in the same meetings, by everyone: who was going to give the next talk, should people take showers in the upstairs bathrooms during nyinthun, and what brand of marmalade we should buy. We threw the I Ching and drew Thunder in the Middle of the Lake. We couldn’t decide whether we were a Cambridge commune or a practice center. There was one notable discussion in which we argued about the size, shape and height of the table we were going to make. It lasted eight hours. We never made the table.

We had external problems, too, in the shape of the sisters McLaughlin and their brother Richard, the Commissioner of Highways for Massachusetts. All three lived opposite us. The McLaughlins were powerful local dieties. They had clout in city hall. They could summon police and health inspectors and stop garage sales at a moment’s notice. We tried to propitiate them by inviting them to tea (they stood us up), sending over a nice Irish boy (Kevin Lyons) to talk with them, and by working for their cancer drive. There was an exhilarating (and temporary) breakthrough in our relations when the McLaughlins finally came to our very successful neighborhood open house at 30 Hillside, our third house. But in the meantime, they complained to the landlord that we had topless women running around the premises. We finally tracked that idea to the source—Christopher Pleim, our dedicated practice coordinator, who at the time wore his beautiful blond hair half-way down his back and would frequently run around without a shirt in the summer.

The afternoon the McLaughlins stood us up for tea, we pulled down the shades, brought out all our private stashes of liquor, consumed all the carefully prepared finger sandwiches and had our first blow-out party. The news of this spread quickly to Tail of the Tiger and soon the Boston Dharmadhatu developed the contradictory reputations for its gentility and its orgies. We often had our blasts in the shrine room. Cocktail glasses—and once, a pair of nylon panties, in a tigerskin design—ended up on the shrine.

During nyinthuns, as one sat unfocusing on the Persian rugs, a small part of the intricate design would detach itself and move off—a cockroach, one of many. They, too, were drawn to Buddhist communes and multiplied somewhat faster than the sangha. The great question was what to do with them. So we asked the Vermont Olympians. We got a lot of interesting advice: 1. Do not kill them under any circumstances. Relate with them. 2. Kill them, but only with natural products—Molotov cocktails of borax, baking soda, pepper… 3. Usher them out, whenever possible, on little pieces of paper, one by one, pointing them gently at the house next door. 4. Have a non-Buddhist kill them (the Shabbas goy approach, used also on larger game, such as lobsters). We finally asked Rinpoche, who told us to have them exterminated, to do a thorough job and to keep the place clean. The first part was easy and a relief, the second a challenge. Apart from our laziness, cleanliness was equated in those days with middle-class uptightness, inhibitions and goal-orientation—the only sin we recognized. But every time we cleaned the place for a grand visitation, we would be delighted and amazed at how elegant it could look. Finally, it began to dawn on us that we could enjoy this sort of environment all the time. It was a big epiphany.

When Rinpoche or Khyentse Rinpoche would come to stay in the house, they were given rooms on the second floor. We would then clean the first and second floors, hoping they would not venture to the third. Khyentse Rinpoche had a disconcerting habit of darting into rooms that were not on public display. He also left behind him an indelible impression of what true aristocracy is—treating his little grandson, us and the attendant monks with the same unvarying awareness, consideration and humor.

The Karmapa’s visit in ’76 was quite a lesson for us as interior decorators and practitioners. We watched ourselves turning our funky Victorian Hillside house into a rococo palace of satin and brocade. We got some idea of how a Vajrayana teacher is treated traditionally. We were also amazed by the whole stretching process we went through—stretching of purses, minds, schedules. The same people who were shocked at the idea of paying $15 a month dues in ’74, contributed $250-500 a piece for the visit. The experience was a mixture of boot camp and mahamudra.

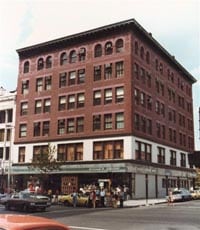

In 1977, after searching for two years, goosed by the Regent (who said one day, when he was sitting in the Upland shrine room, “You have to get out of this place. I can smell your dirty laundry from here.”), we found a large loft off Copley Square. We finally had some neutral space, not tied into our domestic situation, in Boston proper. Not only that, but it was right next to Styx and Chaps, two gay bars, which was extremely convenient for half the membership. It was also close to Filene’s, which houses Boston’s famous bargain basement, which took care of the other half of the membership.

The following year, there was a whole change of the guard. Bob Morehouse, Chris Pleim, Joe Harvey and I all left the administration, one after the other, and central casting sent in a new crew—our inspired ambassador, Winfield Clark, our able new coordinators, William Karelis and Holly Hammond, and their Shambhala equivalents, Ellen and Peter Lieberson. They, and a whole phalanx of competent doers, old and new, now run the Dharmadhatu.

photo by Robert Morehouse

That is not to say that all is smoothness and light in our $2,333 a month haven at 711 Boylston. Women, older people, people with children particularly complain that we do not provide a really accommodating environment for them. But more of them are coming, and in the old days, everyone who came to the Dharmadhatu at Upland felt lonely and somewhat left out of the ongoing domestic situation, while the inmates frequently felt threatened and invaded by visitors. One thing hasn’t changed too much: people are still startled by our predilection for liquor, cigarettes and coffee, and now three-piece suits and certain quaint feudal practices.

But there does seem to be a different quality about the membership today. People seem to be more at ease in the world, more together and more inclined to discipline than the old stretcher cases that used to arrive at the Dharmadhatu five, seven years ago. We were then, by and large, a prize bunch of bewildered delinquents who had no place else to go.

Photograph by Karen Tandee Roper

We seem to have acquired the strength to extend ourselves further, as in Shambhala Training, the whole notion of Shambhala world, of Buddhist teachings secularized, and at the same time to mine more deeply, as in our Buddhist studies, which are getting more demanding, more precise, more doctrinal.

Looking back on the history of the Boston Dharmadhatu, what one sees are milestones of resistance, Rinpoche’s arduous task of taming untamable beings in terms of practice, study, relating to each other and the environment. It has been a slow, often painful maturing process for us, a slow housebreaking process—and the rare experience of watching a true master practice the paramita of patience.