April 4th approaches. On this day in 1987 Chögyam Trungpa passed into nirvana. (For those not familiar with this expression, it is the day he died.) It is a time when his students and others affected by him all around the world pay special homage to his life and teachings. The Venerable Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was the author of many important books on Buddhism, one of the fathers of the Practicing Lineage in North America, as well as the founder of the Shambhala community, Naropa University, and many other organizations.

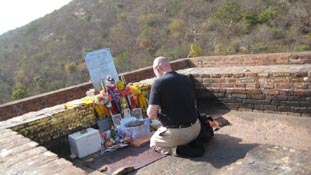

Recently returned from three weeks in India and Nepal, travelling with family and friends, I find it especially meaningful to mark this twenty-third anniversary of Rinpoche’s passing. In India and Nepal, we visited a number of pilgrimage spots and archaeological sites where, as a Buddhist, one can appreciate and pay homage to the great achievements of practitioners, teachers, and lineages of the past. In Bihar, the poorest province of India, one can follow the footprints of the Buddhaas advertised by many companies offering tours in this area. Rajagriha, or Vulture Peak, is the site where Sakyamuni Buddha taught the Prajnaparamita Sutra. A long walk up the mountainside brings pilgrims to a small plateau where a simple altar marks the spot where the Buddha inspired his disciple to speak these words: …”Form is emptiness. Emptiness itself is form…”a liturgy that millions of Mahayana Buddhists utter as part of their daily practice. As we chanted these words and circumambulated the area, we looked out on a vast and empty landscape, which like the insight embodied in this teaching seems vacant yet open and full of potential.

Some hours’ drive from Rajagriha is Sarnath, a small town where the Buddha, after attaining enlightenment, met his first disciples and gave his first teachingon the Four Noble Truths. Buddhist disciples built stupas and other monuments to mark these locations, years after the Buddha’s passing. Today, they are archaeological sites that have been rediscovered and excavated over the last two centuries. You can pay 100 rupees to gain entry to the Stupa marking the place where the Four Noble Truths were preached. Pilgrims from around the world come here, as we did, and local Tibetan monks from Thrangu Rinpoche’s community circumambulate this sacred monument at dawn and dusk. When we went there, just at closing time, a huge “firebird” awash in red, blue and gold, with a long plumed tail, alit in a tall tree near the ruins. It was our last night in India, and she, India herself, seemed to be embodied in this blazing whir of colours that we could not capture or fully comprehend.

The power of these pilgrimage places is palpable, which my Western rational mind finds somewhat unsettling. One enters a Fourth Moment: a moment beyond past, present and future, a moment that is always now. Here, inexplicably but undeniably, one feels the weight of the Buddha’s teachings directly. These are places that demonstrate a peace both profound and vast.

Yet what makes these places worthy of veneration for me, is not this undefined feeling of a “power spot” or a sacred space, but rather their connection to living teachings. We still have the teachings that the Buddha gave. They were preserved by his disciples and his dharma heirs; they were recited, meditated upon, contemplated, and passed down to later generations. For more than two thousand five hundred years people have kept the Buddha’s words alive, adding commentaries and embellishments but also keeping the purity of the original teachings intact, to the best of their abilities.

Last year, Shambhala Publications published The Truth of Suffering: and the Path of Liberation, a commentary by Chögyam Trungpa on the Four Noble Truths, drawn from his talks to senior students. Trungpa Rinpoche was my teacher, and most of what I know about the Four Noble Truths I learned from studying Trungpa Rinpoche’s teachings and commentaries on this topic. In that sense, he introduced me to the Buddha and his teachings, and without that personal introduction, it would be difficult for me to feel the depth of connection I now feel.

When I feel compelled to circumambulate the spot where Buddha gave this teaching, when I feel awestruck by the atmosphere of profound peace, when I gasp at seeing the strange bird of luminosity that inhabits these grounds, all of this is my way of prostrating to the living dharma, the essence of which, although taught by the Buddha, is embodied in the life and teachings of my own teacher. I think this is true for Buddhists of many lineages around the world.

Thus it is that the anniversary of Chögyam Trungpa’s death is at once a time to venerate the past, to celebrate the continuity of the teachings in the present, and to commit myself to the preservation and propagation of dharma in the future. For me, none of this would be possible without the life and example of someone I knew, someone who spoke the dharma in my era, and who connected me to the unbroken thread of sanity that reaches back to the time of the Enlightened One who spoke the truth of suffering and the possibility of cessation to countless beings in India centuries ago.

The places where the Buddha taught, where he was born, where he became enlightened, and where he died are worthy of pilgrimagebut it is the precious holy dharma that we can still hear, practice and embody that makes it so. When as Buddhists we chant “Buddham Saranam Gacchami, Dharmam Saranam Gacchami, Sangham Saranam Gacchami”, “I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Dharma, I take refuge in the Sangha”we are not vowing to take the past as refuge or security. We vow to take the past as an indelible example that we can apply in the present and carry into the future. Similarly, when we celebrate the day that a great teacher died and passed into nirvana, it is not like relatives worshipping an ancestor or expressing their nostalgia and grief for a departed loved one. This day is about appreciating the gifts we have been given in this era: the practice of meditation and the ability to understand our minds and experience through the insight gained from practice. This day is about applying those gifts, and it is about making a gift of our own practice for the benefit of others.