By Grant MacLean

Like many others, on re-reading Born in Tibet, I found that there were spiritual and inspirational layers I’d missed before. But it only slowly dawned on me that the final third of the book, the escape journey, held one of the richest sources of teaching of all.

The challenges confronting the travelers on the escape to India seemed hard to avoid, but I sometimes wondered whether I was really getting it, whether I wasn’t missing something. Maybe I could get a deeper sense of the journey if I could see what they faced, especially the terrain and weather. It occurred to me that Microsoft’s Flight Simulator (FS), with its accurate modeling of world scenery and weather, could help.

So, from around 2005, I began to explore Eastern Tibet in the simulator. It wasn’t straightforward. Landmarks were few and far between and—lacking a highly detailed map—it was never quite clear where things were. Without maps in real world flying, it’s still possible to get where you’re going by looking for airports and airstrips, along with their associated navigational beacons. But unlike, say, North America or Europe, where FS scenery can be compellingly realistic, FS largely ignores Tibet, which even now has little aviation.

So I turned to whatever maps I could find—in atlases, on the web, from Dalhousie University’s Asian Collection and a traditional Tibetan map Akong Rinpoche had annotated and sent to me from Samye Ling.

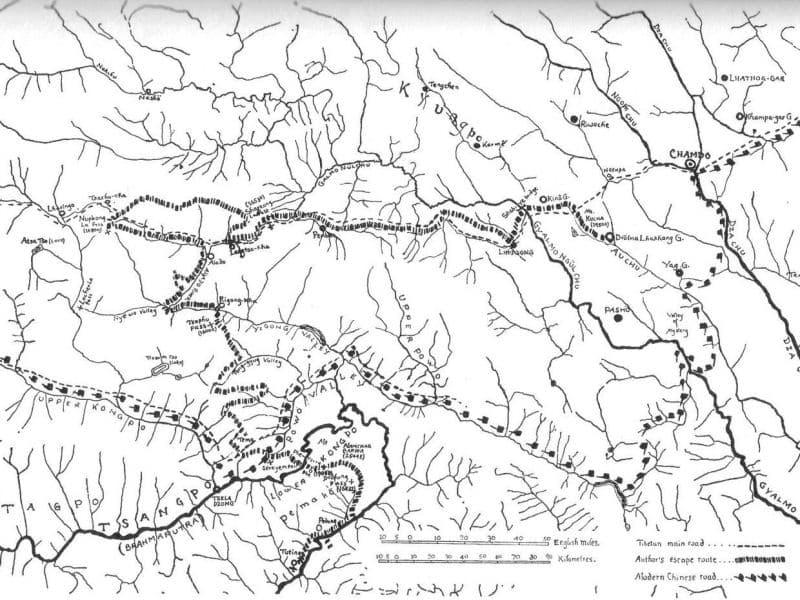

Throughout the journey of discovery, Rinpoche’s map, hand-drawn from memory, proved remarkably helpful, and accurate—all that was really missing were the latitudes and longitudes. His text, too, was full of clear pointers to the way they went, and to what they saw and confronted.

Trungpa Rinpoche’s hand-drawn map from Born in Tibet. © Diana J. Mukpo. Used by permission of Diana J. Mukpo and Shambhala Publications

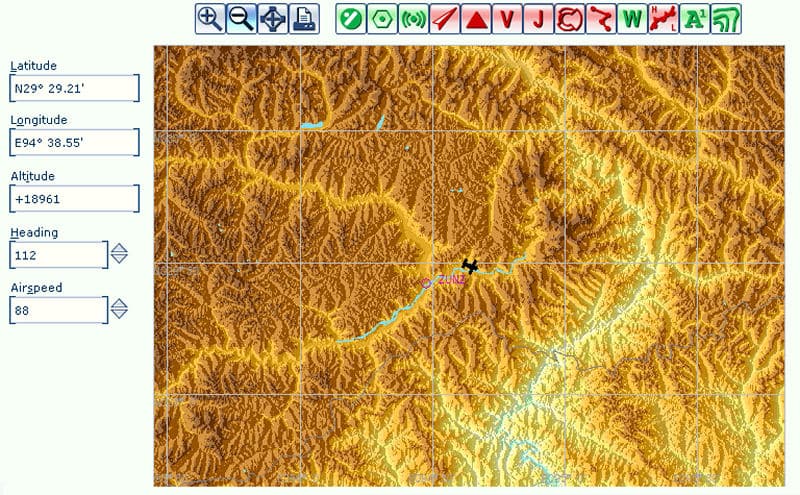

From his crucial reference points, and the combination of maps, coordinates, etc., I found that I could get a basic sense of the terrain by overlaying it on very basic map function in FS.

Flight Simulator map

From this basic layout of the terrain, the shape and whereabouts of valleys, mountains and rivers, I had some sense of what was going on and could begin looking around.

Gradually the outstanding landmarks emerged. Clearly drawn in Rinpoche’s map, the big loop the Brahmaputra made around Mount Namchag Barwaoverlooking the point at which they crossed the riverwas one of the first and easiest to find. As I followed the river on a north-easterly heading, sure enough, there, unmistakably, was the towering, 25,000-foot peak Rinpoche had described.

Flight Simulator cockpit view

From there, following the river valleys as best I could, I headed in a north-westerly direction, scanning the horizon for Nupkong La Mountain where Rinpoche had described it, at the most westerly point of their journey. At the head of the Alado Valley, through which the group had trekked, the peak loomed into view and, below it, the pass they’d traversed.

Nupkong La Pass

Cross-referencing with Rinpoche’s map and text, and the other pile of references, further sections of the route clicked into place, including the Tsophu Valley the group had traveled along at the beginning of the most perilous part of the journey.

Tsophu Valley

As things became more focused, as with the Himalayan terrain, the starving remnants of the group had trekked over after crossing the Brahmaputra, the scenery images increasingly brought home the immensity of what they’d done.

Into India

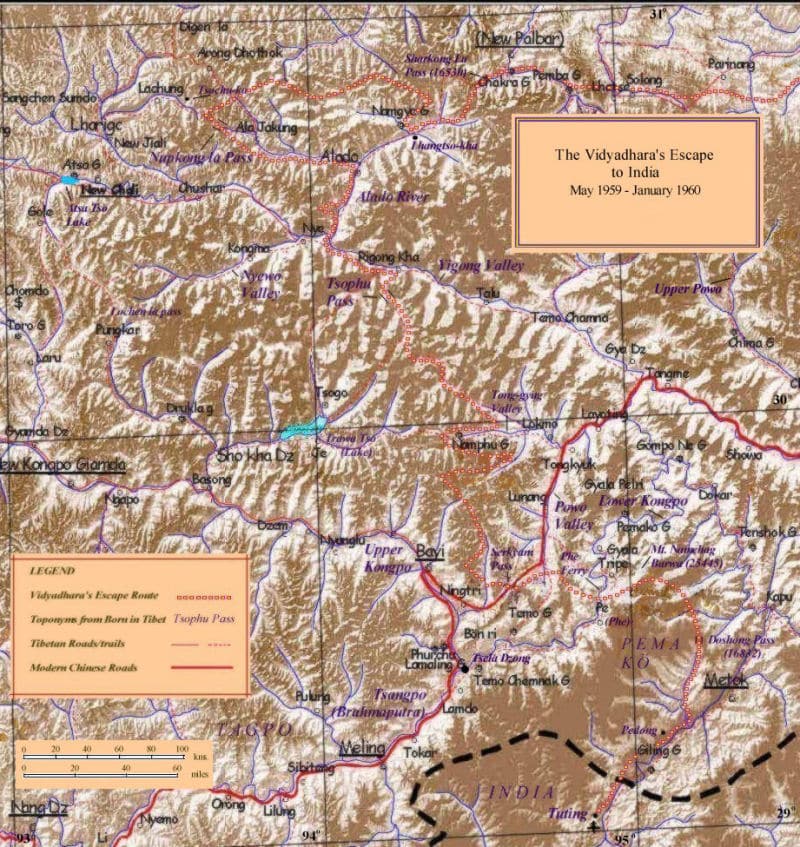

After a while it was possible to map the route onto a terrain map of the area—which indicated again just how accurate Rinpoche’s map had been.

Grant MacLean’s map of the route

But, as that map showed, there were still big gaps in the route. In particular, there was a huge one to the east of Langtso-Kha—the entire first part of the escape, as they headed westwards towards Lhasa. I had only the haziest idea of how they’d made it to Langtso-Kha, where all the intervening landmarks were, or even the location of Drölma Lhakang, the starting point.

The 7th Cavalry arrived in the guise of Google Earth. With its precise photographic detail, I could go down to ground level, look around for smaller details of villages, dirt roads, trails and passes. It was exciting to survey the terrain much as early travelers would have, and then to make informed decisions about the likeliest path to take or where a pass would be, which might or might not be confirmed by what followed.

Google Earth image

But I still couldn’t quite place Drölma Lhakang, or what remained of the original monastery. From Rinpoche’s map, atlases and a nearby airport, I had a rough idea of where it was, but it wasn’t marked on any map, or in GE. Akong Rinpoche’s map was of a large scale and there were several adjoining valleys along which to search.

Recalling that Surmang was located near a small tributary of what was to become the Mekong River, I found the delta—the one that figured so prominently during the Vietnam Warand traced the river northwards. With Rinpoche’s map, atlases, trial and error and a chunk of intuition, I found a river junction with what looked like the ruins of a settlement or monastery, about where Drölma Lhakang should be.

Drolma Lhakang

To its north was a high, snow-covered, mountain that could well have been Mount Kulha, where Rinpoche had lived and meditated before the escape. Moving up the valley, following his map and account, there, just to the west was a lake (black in GE’s satellite’s view, but probably a turquiose blue at ground level), surrounded by five peaks, the Bön tradition’s Five Mothers.

Lake near Mount Kulha

Heading further up the valley, after a while, clearly viewable was the small road or track going westwards over the highlands. Here was the path the group had followed towards the Shabye Bridge.

Highlands Path

With Drölma Lhakang and the first leg of the journey now confidently established, the rest followed.

Although its main features are now vividly in place, finding the route remains very much a work in progress. We will probably never know the location of the Valley of Mystery where Rinpoche hid before the escape—the Touch And Go video scenery is from the general area indicated on his map—or where the party was when they were lost. Other sections are still hazy, at least to me, including the route over the mountains from the Alado Valley to the Yigong Valley, or the location of the plateau where they, and many other refugees, stayed for a few weeks.

“Rising almost perpendicularly to the east of our pass was Mount Namchag Barwa or ‘The Blazing Mountain of Celestial Metal’; its crest glittered far above the clouds, for this mountain is over 25,000 feet high.”

–Born In Tibet, p. 236

Mount Namchag Barwa or The Blazing Mountain of Celestial Metal

Mount Namchag Barwa or The Blazing Mountain of Celestial Metal

© 2009 Grant MacLean