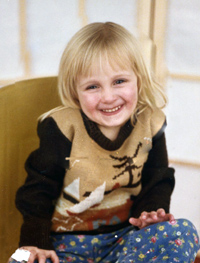

My mother moved to Boulder when I was a baby and became a student of Chögyam Trungpa. I loved “my Rimpoche” ever since I can remember, long before I had a full understanding of who he was. I don’t believe it would have made any difference to me as a child, I just knew that I adored him from the moment I saw him. If anyone had told me it was completely inappropriate to hug this respected and revered man about the knees (actually, I think my mother tried), I wouldn’t have understood why. Wasn’t that a perfectly normal expression of sincere affection? I think I must have shocked some of the important people he was always with. He never seemed bothered by my audacity at all. On the contrary, he always had a moment and a few kind words for me. All my earliest memories are filled with the corridors of Dorje Dzong, the shrine room, and his place in them. At every talk he gave, every festival or celebration, I was waiting to see his arrival and departure like a little shadow. And he always stopped to say hello or smiled at me.

One year, as my mother was lifting me up to receive his Shambhala Day blessing, he took me from her and sat me upon his lap. “Would you like to sit up here with me?”, he asked. I looked up into his face. He had such a gentle smile. “You had to get up very early this morning, didn’t you?” I must have nodded. I remember looking out at an enormous sea of faces, all looking up at us. I was delighted that he’d singled me out this way, but I was also completely terrified by all those people, many of whom I knew, looking at me. It was the only time in my short life that I found it impossible to be cheeky and charming. I turned my face from them into his golden robes. I desperately wanted to stay this close to him, just me and him. He said, very softly,

“You can sit on my throne anytime.”

And he handed me back down to my mother.

Almost twenty years later, my oldest friend was in town and wanted to visit the shrine room. I hadn’t been there very often since Rinpoche’s death, it had become too sad without him for me to bear. But with her, we could quietly share our childhood, standing there in front of his throne together. As we looked up at his photograph, she asked me if I’d ever taken him up on his offer to sit there. Of course, I hadn’t. It never occurred to me that I should, it was more than enough that he’d extended the invitation. “Go ahead”, she said as she walked towards the doorway. “I’ll keep an eye on the stairs.”

I felt like a criminal as I climbed the wooden steps up the side of the throne. What on earth would I say if someone saw me? “Oh, it’s okay, Rinpoche said I could.” Right. They’d likely toss me out before I could finish a sentence. I nervously sat on the stiff brocaded cushions and looked out at the shrine room again. The faces weren’t there. And neither was he. The room was empty and silent. All that mattered to me in that room, on that throne, was gone. There was nothing for me there anymore. And there still isn’t. I was crying as I slipped down the stairs in my socks. I didn’t say anything to my friend, and she didn’t ask.

I don’t know what I hoped for, sitting up there with his photograph. It didn’t make me feel closer to him or bring me any peace. I only missed him more. Thinking of him now, I can find solace in the knowledge that he loved me too. I know this is fairly insignificant in the larger context of the world, but it means everything to me.