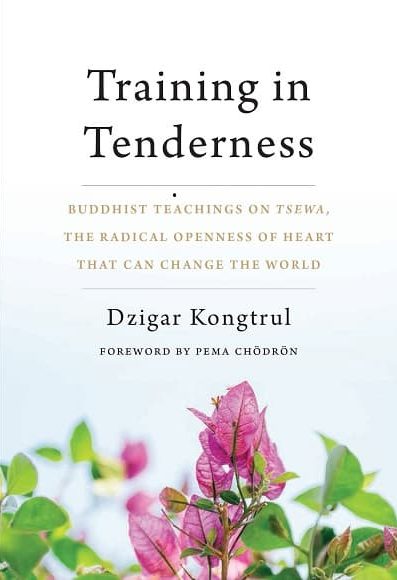

Book Review by Clarke Warren

There are myriads of books out these days on compassion and love, just as there is a steady stream of online courses, teachings, seminars, and retreats claiming the same subject matter as their base. There are of course great timeless classics on the subject, such as the Bodhicharyavatara and its commentaries, and the Lojong (Mind Training) of Atisha and its many guidebooks, such as, in English, Training the Mind by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, among many others. The Dalai Lama has been a beacon of modern day teaching on compassion. However lately, as much as the times sorely need more love and compassion in a world so deficient in them, it is difficult to navigate the massive volume of books and presentations on compassion and love, and determine which might be genuinely helpful personally and societally. And discern which are more inclined toward platitudes of doctrine, parched academic reductions, moral prescriptions or faddish renditions of this subject which, despite itself, is ironically being beaten into overload and redundancy. So where does this thin volume by Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche come into play amidst this frayed profusion?

The book immediately attempts to cut itself out of the herd of predictably loaded or redundant use of the word love. It engages the Tibetan word tsewa, and the book proceeds to demonstrate how this word delineates a human quality that the author likens to the oxygen that supports life altogether, is innate and at the heart of life’s creative process. It is the open hearted tenderness innate in the nature of all sentient beings as well as the phenomenal world. “It is the heart of Mother Nature herself.”

At first, such a claim seems more than a bit presumptive and even schmaltzy and evangelical. So what about the depressive and oppressive side of life and experience, and the ever gathering clouds of negativity, conflict, war, social and political chaos and acrimony that seem abundantly more evident and pronounced in contemporary life than tsewa?

Rinpoche proceeds to bring those very contradictions into play. He engages the common sentiments of grudge, disillusionment and the “injured heart” , and rather than seeing them as contradictions to tsewa, presents them as indications of the necessity for tsewa. ”The painful nature of samsara is the most important reason for us to find ways to keep our hearts continually open with tsewa.” Then these very impediments might themselves become conveyances of tsewa.

He does not expect one to naively accept and adopt tsewa. In this way, this book compels one to gauge oneself and one’s life in relation to what it has to say and suggest with regard to tsewa, rather than jump on board a rosy and naive “all you need is love” agenda. The book could be regarded as a challenge rather than a prescription. Rather than suggesting one should adopt tsewa, it is a matter of “removing the impediments to tsewa”, then discovering its qualities and power in the context of one’s everyday life. “We will even come to see our ‘misfortunes’ as helpful.”

If this is indeed possible, one needs to find out for oneself, and Rinpoche suggests, we must engage our critical intelligence and employ meditative discipline and insight to do so.. Rinpoche includes in his presentation some contemplations and analysis that serve this purpose by thoroughly examining the matter, and bringing our perspective and intelligence into direct experience.

Rinpoche suggests we habitually keep our mind in a state of crisis through our endless preoccupations and fixations, rather than relaxing, which is a matter of coming to trust ourselves, and which is the way to invite and engage tsewa.

Of course the fundamental Mahayana Buddhist edict is the inseparability of compassion (tsewa in this rendition) and wisdom (critical intelligence and direct insight), yet Kongtrul Rinpoche makes these lofty principles personal and accessible. He challenges one to engage with tsewa, and consequently wisdom and compassion, in terms of one’s own life, rather than just relying on doctrine, concept, pretension or wishful thinking. And thus also approach the possibility of genuinely being of help to others, which is the trajectory of tsewa.

Although the emphasis of the book is centered around the appellation tsewa, the book does relate and link the term and its import to classic Buddhist principles and dynamics, such as clinging to the self as the primary obstacle, the truth of suffering, the primacy of intention, loving kindness, compassion, bodhicitta, the bodhisattva vision, mindfulness and vigilant introspection and so on. Tsewa could be said to be the life force of all of these. He weaves these primary and essential cornerstones of Buddhist view and practice into the discussion of tsewa like placing washed dishes away into their proper and accessible place in the cupboard. He likewise references Santideva, Chandrakirti, the Dalai Lama, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Tulku Ugyen and others in a manner like referring to close relatives and friends, and relays lineage stories which adorn the subject with vivid examples like conveying recent family news. He concludes the book with two primary and vivid situations to which tsewa has much to contribute, relationship and death. And ends with “the world and the future”, thus relating one’s own connection to tsewa to what might actually address and remedy the state of chaos in the world.

Training in Tenderness, as a brief (105 page) yet profound, rich, lyrical, clear, simply expressed, and utterly practical volume, joins a select few dharma books which have succinctly placed vast and profound teachings handily and simply into the palm of one’s hand, such as Meditation in Action by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind by Suzuki Roshi, and When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön. These books are not so much composed as distilled directly from raw experience. You might want to buy two or three copies of Training in Tenderness, because it is the kind of book that you may well want to give to others, as an act of tsewa.