We should keep all these stories of the beginning of Buddhadharma in America. I personally feel very grateful for the existence of the Pygmies. Without them, there was no possibility that we could have established a country meditation center, but due to their existence, it happened. Rocky Mountain Dharma Center was one of the first rugged places we have had to conquer. It is very important that we should put more energy and effort into it. -Chögyam Trungpa.

“Conquering Ruggedness” by Barbara Stewart. Vajradhatu Sun, February-March 1981

One day, Zanto, Ragatara, Emur, and some other Pygmies were up Left Hand Canyon tripping on acid when Clarke Warren walked into their campsite. Clarke’s sister lived in that area, and he often stayed there and took hikes in the mountains. Clarke told them, “There’s a Tibetan lama coming to town, would you like to see him?”

Zanto barely knew what a lama was, but he said, “Sure, why not?”

A few days later, Clarke and Polly drove out Arapahoe to the Pygmy Farm to tell us that Rinpoche was giving a talk at CU in a few days.

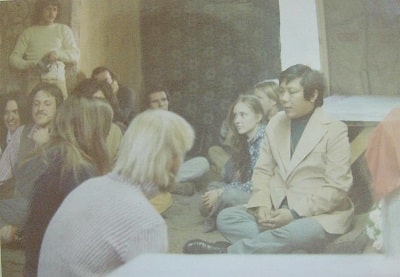

When the time came, we smoked some hashish and drove our rag-tag caravan of cars to the talk. Karl Usow introduced Rinpoche as the author of Born in Tibet and began his remarks with “Another mountain has come to Boulder.”

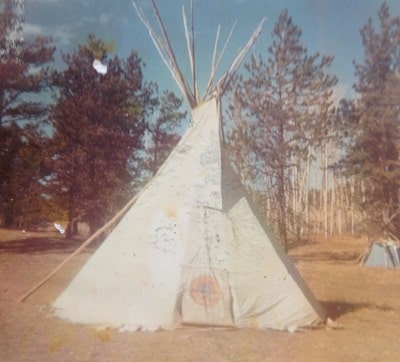

… When I had first heard that a Tibetan lama was coming to town, I was living in my teepee and reading The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa, translated by Garma C.C. Chang. I was fascinated by this great yogi, but was having trouble understanding some of the teachings, with their mix of poetry and foreign terminology. Then Su Ming Chu told me, “This lama who is coming is descended from Milarepa; he is a holder of his lineage. He can explain the book to you.”

I said, “Cool.” Who wouldn’t want to go see him? I was picturing a yogi like Milarepa, who could fly and put his handprint in rocks. I imagined that he wore white cotton clothes and danced half-naked in the mountains and lived on barley flour and nettles. Or something like that.

But watching Rinpoche walk onto that auditorium stage, my first impression was that he was in pain. He was a little crippled guy wearing Western clothes. He sat in a simple chair in the middle of the stage, which was empty of any decoration or adornment. He looked so alone. And he couldn’t sit still, probably because of residual pain from his car crash.

All my preconceptions were shattered, and my heart was broken.

After Rinpoche sat down, he said nothing for a few minutes, or maybe just a few long seconds. Then he said, “Space.” Then nothing. Then, “This journey is lonely without a friend.”

After Rinpoche’s talk at CU, most of us Pygmies wanted to have a deeper relationship with him. Someone brought home Meditation in Action, and some of us read it. Others read Born in Tibet. Most of us were not very intellectual, and some hadn’t read a book in years. So as accessible as those books were, they did not quench our longing. When we got the chance, we made arrangements to see Rinpoche at his house in Four Mile Canyon for personal interviews. We discussed the protocol, what to do? Some of us decided to ask him to be our teacher.

The earliest interview was a group interview with Zanto, Mau, Tim, and maybe others. John Baker greeted the Pygmies and showed them into Rinpoche’s bedroom. They sat on a mattress on the floor at the foot of the bed, with their beards, long hair, leather clothes, unwashed looks, and smiles. Judith Hurley had donated some sheets, tie-dyed in big blotches of the Tibetan colorsâ??red and yellowâ??to cover the four-inch-thick Salvation Army mattresses.

Rinpoche had long underwear bottoms and a white top on and was sitting in his bed, which was a mattress on the floor, hippie style. A bottle of Johnny Walker Red was on the table beside him.

The Pygmies said that they had been at the talk at CU.

Rinpoche asked each of them what their religious knowledge or experience was. Zanto said, “Kumi and Madame Blavatsky and the Secret Doctrines.”

Mau told him about some study of Paramahansa Yogananda and Babaji and other Eastern teachers and having met Swami Satchidananda.

They chatted for a few minutes. The Pygmies told him that they lived in a commune on East Arapahoe. Rinpoche seemed very interested. Then he asked, “Why are you here?”

“We’re bodhisattvas, just like you,” Zanto said, whether or not he really knew what that meant. (A bodhisattva is a person who has vowed to continue to be reborn to benefit suffering beings.)

Rinpoche took a drink of scotch and said, “We’re going to be together for a long, long time.” Then he added, “We have a lot of work to do.”

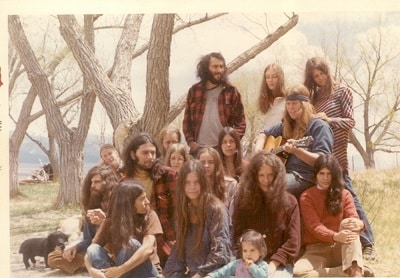

… Over a period of a few months in the winter of 1970â?”71, the Pygmies and Rinpoche developed a close relationship. From one point of view, it was a student-teacher relationship, with the Pygmies going to talks, practicing meditation, and receiving guidance from Rinpoche on their meditation practice and their personal lives. But in other ways, it was a friendshipan incongruous meeting of minds.

Rinpoche was a king, immaculate in every detail. His body moved in perfect elegance, despite being paralyzed on the left side. He always dressed meticulously, even when he was wearing casual shirts, suspenders, and Bermuda shorts. His speech was perfect Oxonian English, clear and pure, although a bit high and sometimes squeaky because of his traffic accident. And his mind. What did I know of his mind? I just knew that he was the most interesting person I had ever met.

The Pygmies, on the other hand, in addition to being rebels against the polite Emily Post style of good manners, had no knowledge of Buddhist or Tibetan or Asian customs of reverence and devotion to great teachers. We would drop by Rinpoche’s house without notice, day or night. And even after we learned that the term “Rinpoche” was an honorific meaning “precious one,” we called him “Rimp” for short. We didn’t stand up when he entered a room, which was a traditional Asian sign of respect. In fact, we often didn’t even provide an aisle for him to walk to his chair, so sometimes he had to step over one of us sprawled on the floor.

Rinpoche responded to our sloppiness and lack of decorum with friendliness and warmth, welcoming us into his living room without question and into his talks without charge. He offered us wine in the afternoon and food in the evening. He chatted with us, answered questions, and flirted with the Pygmy women.

His Four Mile Canyon house became a community center and the living room was the meditation hall. Any number of people might be hanging out in the kitchen at any given time. John and Marvin lived upstairs ..

At some point the Pygmies invited Rinpoche to dinner at the Pygmy Farm and he accepted. It was exciting for us, a big deal. We spent hours preparing for him. Joanne and Jodi and others put together a menu of our favoritesâ??buckwheat noodles with whole-wheat gravy and a generous serving of zucchini from our garden…

After dinner, we sat around the living room on the madras-covered cushions and pillows on the floor and smoked dope. We were drinking Mu tea; Rinpoche was drinking Johnny Walker Red with orange juice. We passed around a hash pipe that Emur had carved from deer antler, and each of us took a toke. When the pipe got to Rinpoche, he took it and asked, “Which end?” We laughed, then he put it to his lips, (whether he smoked or not, I don’t know) and then passed it on.

Mau and Nurti’s daughter Dharma had just been born, so we said, “Oh we have a baby! Could you bless her?” And he did; by touching her forehead.

One of us asked, “What is meditation?”

Rinpoche said, “It is nothing.”

“Is it no thing?” I asked.

“No,” he said.

Someone asked, “How do you do it?”

He said, “Let it be.”

Someone asked, “Don’t you need to purify yourself in order to achieve enlightenment?”

Rinpoche said no, that if that were true, then no one in New York or other polluted places could become enlightened. But that is not the case, enlightenment is available to everybody.

A week or two later, John Baker drove out to the Pygmy Farm with a message from Rinpoche. He said that Rinpoche had initiated a search for land to establish a rural dharma center in the Colorado mountains. John was there to ask if the Pygmies were willing to move to the land and become the nucleus of the new dharma center.

I said that we would be delighted, and John asked, “Don’t you need to have a meeting and reach an agreement?”

I said, “Yes we do, but the agreement will be to do it.” And it was; … most of us thought it was a great idea. We would have some land where we could permanently establish our commune, and be Pygmies forever.

The New World

The land was at an elevation of about 7,500 feet and there were no roads or buildings on the property. We parked our caravan in a line along the ridge above the valley and looked down at an endless carpet of deep, freshly fallen snow. It felt like being Christopher Columbus facing the New World. Or the first people on the moon. We were Trungpa’s Marine Corps consigned with capturing and holding a beachhead against all challenges until the fully trained and equipped army could arrive.

The bright white light of the field of snow was broken by deep green ponderosa pines that rose into the distance against a brilliant blue sky. A huge rock outcropping rose majestically above the landthe local deity of a wilderness waiting to be tamed. Below its benevolent gaze, a stream bed divided the land into two parts: the high forests and the low meadows; the pines and the aspens; the rocks and the snow-covered grass. We chose the nearer, the gentler, the more open meadow area for our first camp….

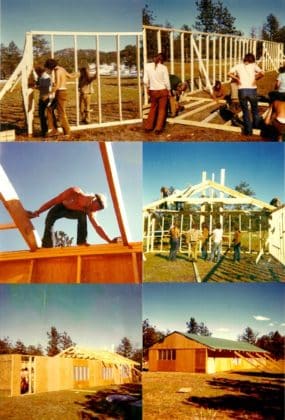

Over the next week, the snow melted and we were treated to a beautiful Indian summer. We took advantage of the good weather to build the large main building and some personal housing. Tom Ryken was the boss, being a master builder with years of experience. The rest of us were inexperienced labor. In those first weeks, other people arrived and a few people left. Before we finished the first building, we slept in tents. The nights were cold and those with partners were glad to share our body heat. Others without partners had to manage on their own …

The whole situation was crude; the focus was survival.

As soon as we could scrounge the materials, people built small houses and moved into them. We got slabs of wood from a nearby sawmill and used them for both our shacks and campfires. The first houses included the Klamers’ dome, Hennigen’s yurt, the Rykens’ A-frame, and other small A-frames and shacks …

We held daily meditation sessions in the main building. Dust would rise from the dirt floor during walking meditation. Sometimes Rinpoche would join us. One time he performed a children’s blessing; other times we just hung out.

One night after dinner, Rinpoche was sitting with us on a couch in front of the shrine with the offerings on it: five bowls, a picture, tea, and incense. Rinpoche asked, “What do you do at night?” So somebody went over and lifted up the shrine cloth and folded it back over the offering bowls. Under the shrine cloth was a TV.

This was before VCRs or cable, and we could just pick up one channelâ??Channel 5, KGWN-TV from Cheyenne, Wyoming. So the group of us watched TV with Rinpoche. That evening’s movie was Children of the Damned.

Rinpoche said, “Hmm, Tibetan Buddhism in America,” and we all laughed.