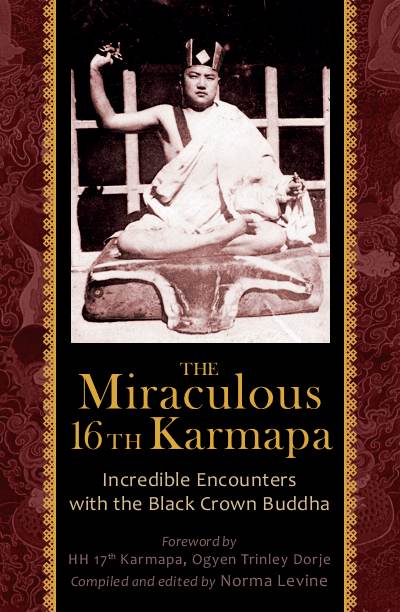

The 16th Karmapa Rigpe Dorje was once asked by a Westerner what one should do if one witnesses a miracle. The Karmapa responded, “Regard it as completely ordinary.” The Karmapa himself continuously demonstrated this interface of magic and the ordinary world in every turn of his life, as documented in the book The Miraculous 16th Karmapa: Incredible Encounters with the Black Crown Buddha. The title of one of the stories in this book best summarizes the scope and character of the entire volume: “Encounters of the Immediate Kind with the 16th Gyalwang Karmapa.”

The 16th Karmapa Rigpe Dorje was once asked by a Westerner what one should do if one witnesses a miracle. The Karmapa responded, “Regard it as completely ordinary.” The Karmapa himself continuously demonstrated this interface of magic and the ordinary world in every turn of his life, as documented in the book The Miraculous 16th Karmapa: Incredible Encounters with the Black Crown Buddha. The title of one of the stories in this book best summarizes the scope and character of the entire volume: “Encounters of the Immediate Kind with the 16th Gyalwang Karmapa.”

For Tibetans, the power, magic and influence of the enlightened embodiment of the Karmapas have been famed and revered for centuries, covering a span of now 17 Karmapa incarnations since the first in the 12th Century CE. The Karmapas’ principal renown is for their realization and embodiment of Mahamudra, the enlightened state of mind and the teachings leading to it. They hold the realization and teachings of the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, dating back to the 11th Century Indian master Tilopa, who received the teachings of Mahamudra directly from the primordial Buddha Vajradhara. The lineage includes such illustrious persons as Marpa, Milarepa, Gampopa, and a garland of many more over centuries. Karmapa in particular embodies the activity of that enlightened mind and lineage. Part and parcel of that compassionate enlightened activity are events and situations that often seem magical. But that magic is not necessarily spectacular or outlandish. As Ringu Tulku Rinpoche says in one of the accounts, “We Tibetans see Karmapa as almost like a Buddha, so everything is special in a way, and nothing is more special than anything else.” The primary magic of the Karmapa was his presence itself, as demonstrated by many of the stories in this book, and that presence had a marked effect on the people and environment around him. So while there are ample accounts of the Karmapa leaving his footprint in rock or on water, there are even more of the Karmapa leaving his imprint vividly in people’s minds and lives.

The book begins with the Karmapa’s earlier life in Tibet, then in exile in Sikkim and India, then proceeds with his monumental visits to Europe and America. It covers a wide swath of Karmapa Rigpe Dorje’s life and activities, but also his illness with cancer, his death in America, and his cremation in Sikkim — each an indelible demonstration of the Karmapa’s remarkable character and enlightened activity.

The 16th Karmapa Rigpe Dorje arrived in the West in 1974 with utter confidence, majestic presence, boisterous sense of humor, and beaming warmth that conquered the hearts and minds of people wherever he traveled in “the new world”. His effect on people was transformative, as indicated by so many of these personal accounts. He was hosted in America by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who lauded the Karmapa as a great enlightened king, and Trungpa Rinpoche went to great lengths to expose his students to the Karmapa’s brilliance and spiritual blessing. Chogyam Trungpa once remarked, “His Holiness Karmapa only sees people’s basic goodness.”

This book coalesces a wide variety of accounts of and encounters with Karmapa from people representing a broad diversity of life and situations. It is a collection of devotional chronicles, not from the point of view of pious belief or personality cult, but from the seminal influence of direct interactions with Karmapa. One could argue that the book is recollecting Karmapa to the converted, and indeed some of the accounts are written with devotional and doctrinal language familiar only to the initiated and educated Buddhist. Yet it would take a blunt and blind cynicism to deny the authenticity of the nearly 400 pages of accounts, or attribute them only to the affected sensibilities of the devout. For those readers who are indeed not particularly predisposed toward the authenticity of many of these stories, the book may serve to open minds to wider possibilities than are commonly assumed by modern materialistic culture, or, for that matter, by more suspiciously sensationalist supernatural literature. One of the indelible lessons demonstrated in these many stories is that magic is indeed not “supernatural”, but implicit in the most basic nature of the world and its inhabitants. Magic is utterly natural, and nature is utterly magical, if seen by the naturally awake mind, and as demonstrated by the Karmapa through these firsthand accounts.

This book coalesces a wide variety of accounts of and encounters with Karmapa from people representing a broad diversity of life and situations. It is a collection of devotional chronicles, not from the point of view of pious belief or personality cult, but from the seminal influence of direct interactions with Karmapa. One could argue that the book is recollecting Karmapa to the converted, and indeed some of the accounts are written with devotional and doctrinal language familiar only to the initiated and educated Buddhist. Yet it would take a blunt and blind cynicism to deny the authenticity of the nearly 400 pages of accounts, or attribute them only to the affected sensibilities of the devout. For those readers who are indeed not particularly predisposed toward the authenticity of many of these stories, the book may serve to open minds to wider possibilities than are commonly assumed by modern materialistic culture, or, for that matter, by more suspiciously sensationalist supernatural literature. One of the indelible lessons demonstrated in these many stories is that magic is indeed not “supernatural”, but implicit in the most basic nature of the world and its inhabitants. Magic is utterly natural, and nature is utterly magical, if seen by the naturally awake mind, and as demonstrated by the Karmapa through these firsthand accounts.

This book of roughly 80 accounts fills in between the broad strokes of the Karmapa’s public activities with personal portraits of blatantly magical events as well as the more subtle yet decisively influential events that accompanied him at every turn, in Tibet and India, North America, and Europe. As one makes their way through these sometimes amazing, sometimes hilarious, sometimes mundane, sometimes scary, sometimes intimate, sometimes public accounts and stories, it becomes vividly clear why the legacy of the Karmapa is so enduring.

Occasionally events around the Karmapa were indeed inexplicable and astounding, such as a photo, untampered with, of the Karmapa on his throne but with a translucent body, as told by the photographer.

Several of the stories record the powerful effect when the Karmapa performed the “Black Crown Ceremony”, during which the Karmapa dons an ancient sacred hat said to be able to impart a direct glimpse of enlightened wisdom. He assumes his identity as Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion. He then projects the power of enlightened wisdom and compassion to all present. These ceremonies were often performed before thousands of people, and as the stories attest, were highly potent in affecting the minds and lives of those present. Some of the stories also demonstrate the efficaciousness of the “Karmapa Black Pills”, a rare and powerful spiritual medicine dispensed by Karmapa. One story recounts the Karmapa’s dream in Colorado of what became the Namchen Banner, or “Dream Flag”, which the Karmapa stated would make dharma flourish wherever it is flown. Many of the stories recount vital verbal interchanges with Karmapa, and some revolve around the Karmapa’s ability to see the minds of people and affect them directly, without words.

The Karmapa met and interacted with kings, movie stars, artists, the very wealthy, politicians, world leaders, spiritual leaders and teachers such as Pope Paul VI, Swami Muktananda and the entire spectrum of Tibetan Buddhist lamas, as well as innumerable common people in everyday circumstances. He seemed to treat everyone with the same amazingly engaging demeanor and warmth. His life was one of constant fresh encounter, inclusion, and compassionate service. While visiting America, he went to meet the Hopi tribe in Arizona, with whom he felt a spiritual link, and an account chronicles his bringing rain to their lands during a severe drought, and fulfilling an ancient Hopi prophecy predicting his visit. When he traveled, he was sometimes hosted in palatial splendor, while at other times and places staying in very simple quarters, with no indication of preference by him for either. The wide variety of accounts by a wide variety of people and in a wide variation of circumstances gives the book a credibility that transcends anything that could be accomplished by a single-authored, well-crafted biography, and demonstrates the utter openness and engagement of the Karmapa with any and all circumstances and people he met with.

Occasionally events around the Karmapa were indeed inexplicable and astounding, such as a photo, untampered with, of the Karmapa on his throne but with a translucent body, as told by the photographer. On another occasion, a photo reveals the figure of the dharma protecter Mahakala on the Karmapa’s body. One story witnesses his transformation into the Medicine Buddha. One attests to the consistent ability of the Karmapa to precisely indicate the place and identity of the rebirths of accomplished Buddhist teachers and practitioners. And the accounts of the early life of the Karmapa are replete with wonders.

Some of the more endearing accounts are with bird merchants and collectors, as Karmapa himself was an avid expert on, lover of and keeper of birds. He knew or learned exactly where to go and who to meet to acquire the birds he sought, and his birds traveled with him as part of his entourage. He astounded the most expert of bird specialists. And his relationship with his birds itself was special. He regarded birds as having a particularly good disposition for the direct transmission of spiritual blessing, and would place birds in meditative states as they sat on their perches.

Contributions to the book were drawn from those within the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, such as Gyaltsab Rinpoche, Ayang Rinpoche, Kalsang Rinpoche, Dorzang Rinpoche, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Sister Palmo, Ngodrup Burkhar, a translator for His Holiness, Zhanag Dzogpa Tenzin Namgyal, a past General Secretary to Karmapa, and others. Many then came from Western Buddhists who became so devoted to Karmapa, or whose spiritual path was profoundly affected by him. Some served Karmapa directly and spent extended periods of time around him. Some of the best stories, on the other hand, are of people who had never met or known about Karmapa, were not Buddhist, and had no idea about him until their encounter with him. Some of the stories are more extended in their narrative, charting the early years of Karmapa, then the development of Buddhism in the West; yet some consist of brief snapshots that convey an immediacy and sharpness of interactions with Karmapa. The entire list of contributors gathered together by Norma Levine is too long to mention here. One should read the table of contents to see its extent.

Some of the stories are highly humorous, and reflect the Karmapa’s abundant sense of humor and playfulness. In one, the Karmapa was staying in a rural setting, and asked whether there were bears around. Stephan, a Western student serving the Karmapa, in a sly conspiracy, dressed in a bear costume and came rumbling out of the forest in a mock confrontation before the Karmapa’s eyes. Afterward, Stephan in his bear costume climbed the stairs to the Karmapa’s porch, presented a ceremonial white scarf, and was duly blessed by the Karmapa’s hand on his bear nose.

The Karmapa thoroughly enjoyed visits to Disneyland, and was photographed with actors in Disney cartoon character costumes, such as Micky Mouse and Pluto the dog. Once he remarked that he liked the “Pirates of the Caribbean” with its tour through scary animated scenery and robotic characters best because it was like the bardo, the intermediate state between death and rebirth.

All the while, the Karmapa was constantly engaged in transmitting the major spiritual transmissions, empowerments, and blessings of the Kagyu lineage, and in starting centers for the practice and study of Buddhism. He performed the powerful hallmark Black Crown Ceremony wherever he traveled. In addition, there was teaching in everything he did. As Dorzang Rinpoche writes in the book, “Some of my Western students ask me, ‘What kind of teachings did your root guru (Karmapa) give you I say, ‘Nothing. When I go to see my root guru, I just sit there. Whatever he does is a teaching for me.'”

But not all encounters with Karmapa were pleasant or endearing. He seemed many times to naturally create challenges and/or difficult circumstances for students to work with as part and parcel of their spiritual journey. And students often felt naked and raw around him. Or else, from another perspective, just being in the presence of someone who is continually awake and fully engaged with the world is itself challenging to a mind that is in any way habitually inclined otherwise. Also, in another vein, some of the more potent stories recount the strong and compassionate effect of the Karmapa on the extremely ill and dying, and those in mental distress.

The book is peppered with photos from the Karmapa’s life and travels, many of them rare portraits of remarkable times and the remarkable entourages of great spiritual teachers that accompanied Karmapa.

The one area I found insufficiently documented in this otherwise exhaustive collection were the events in Karmapa’s life involving everyday people in Asia. While the accounts by Asian lamas of particularly impressive and famous events are abundant, stories from the more common strata of Asian communities and cultures are lacking. For instance, while living in Sikkim for a few years, I heard the eyewitness story that emanated from an entire village of when the Karmapa was invited to intervene during an epidemic hitting the village, attributed to the displeasure of a powerful local deity. Everyone present in the village saw the Karmapa visually transform into the dharma protector deity Mahakala and subdue the local deity. Karmapa then arranged a truce with the deity, and prescribed a daily ritual and torma offering to it. After that, the troubles suddenly and dramatically abated. Karmapa indeed was continually providing such compassionate and powerful services to the people of Tibet, Sikkim and elsewhere, and was often the arbitrator between the seen and unseen worlds. Perhaps there can be a second volume inclusive of these marvelous accounts.

As the Karmapa’s name itself indicates, he is the embodiment of the activity of enlightened mind and life. His activity is the continual interface of awakened mind with everyday worldly events. In this regard, this generous and celebratory book strikes to the very core and purpose of the Karmapa’s life and lives.