by Jim Lowrey

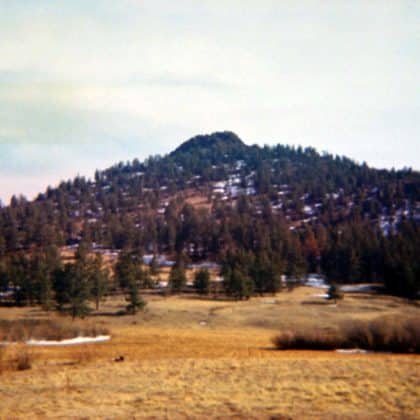

“There was a valley with pine trees and rocks that had never been cultivated. Should we buy an empty desolate valley without any facilities? We drove through and the only thing we could see was lots of wild horses. Nothing was civilized at all in terms of electricity or the establishment of any kind of human habitation. Nonetheless, I decided to take this place because it felt wholesome and good. There was a rocky point, which we now call Marpa Point, and the surroundings, which were nice areas, and everything seemed to be ideal. It was as if somebody had been waiting for that particular land to be occupied, and we became the first people who actually trod on it. I said, ‘Yes, let’s do it, let’s buy it.'”

-Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, as quoted in the Vajradhatu Sun, February-March 1981

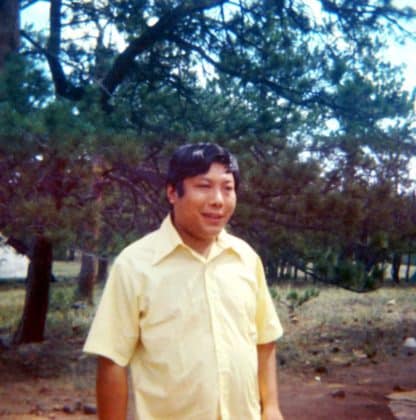

In the spring of 1971, after being kicked out of the Pygmy Farm in Boulder, Colorado, the Pygmies were homeless wanderers for a few months. We camped out in the various National Forests in the mountains west of Boulder, waiting for the imminent purchase of the land. Rinpoche had asked the Pygmies—a hippie commune that had connected with him after his first talk in Boulder in November 1970—if we would pioneer a mountain practice center near Boulder, and we agreed to do it. After Rinpoche visited the land and decided it was a good choice, Jonathan Eric donated a substantial down payment for the purchase, and negotiations began with the landowner Mr. Pavel, who owned or controlled a lot of land around Red Feather Lakes, Colorado.

But the closing was postponed a number of times and negotiations stalled. I don’t know the details of the negotiations, or the sticking points, but through the summer of 1971 we camped out and cooked over open fires. After dinner we would sit in a circle around the fire and smoke dope, drink wine, and sometimes play music in the fire ritual style that Zanto and others brought back to the Pygmy Farm from New Orleans. In June, Rinpoche gave us the Sadhana of Mahamudra, with the instructions “Read this,” so we chanted it together around the campfire, one time, while tripping on psilocybin mushrooms.

Early in the morning of September 16, 1971, an unseasonal snowstorm dropped almost two feet of snow on the Pygmies’ camp in the mountains west of Boulder. When I awoke at dawn, I could sense something strange as I lay in my sleeping bag next to my partner and our one-year old child. I lay there, waiting for my waking consciousness to tell me what I already knew. The silence. The total silence that once you have experienced it is never forgotten. The blanket of silence that means deep soft snow has hushed the earth.

When I unzipped my tent it collapsed under the weight of accumulated snow. I stuck my head outside and saw that all the tents were collapsing. There were women with babies in our group—three or four children at that time. So we dug ourselves out of the drifts, gathered some clothing and sleeping bags, loaded up our trucks and cars, and drove down Four Mile Canyon to Rinpoche’s house. Rinpoche wasn’t there; he was at Tail of the Tiger (now Karme Choling) in Vermont, but we camped out in his house, in his living room. We were running out of places to be and Winter was coming.

But that day, September 16, 1971, the day of the big snowstorm, is when the land deal closed. The terms were settled, a down payment was made with Jonathan Eric’s donated money, and the paperwork was signed. A call came to Rinpoche’s house from our lawyer, John Roper, who said, “It’s done. We own it.”

So the next day, we loaded up our trucks and headed up into the mountains northwest of Fort Collins to the promised land. That afternoon, the group of Pygmies and a few others—maybe 20 people in all—arrived on a desolate, unihabited piece of land. It was at an elevation of about 9,000 feet in the Rocky Mountains, and there were no roads and no buildings.

We parked our caravan in a line along the ridge above the valley, and looked down at an endless carpet of deep, freshly fallen snow. It felt like being the first people on the moon. The bright white light of open fields of snow was broken by deep green ponderosa pines that rose into the distance against a brilliant blue sky.

A huge rock outcropping, later to be named Marpa Point, rose majestically above the land—the local deity of a wilderness that waited to be tamed. Below its benevolent gaze, a stream bed divided the land into two parts: the high forests and the low meadows; the pines and the aspens; the rocks and the snow-covered grass. We chose the nearer, the gentler, the more open meadow area for our first camp.

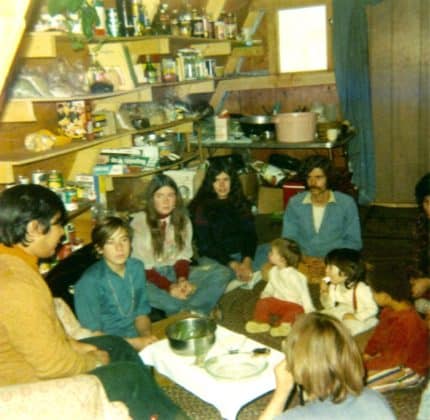

To pitch our common tent, we rolled huge snowballs, like the kids that we were. But instead of building a huge snowman as would children at play, we pushed the snowballs aside and strung a large canvas tarpaulin between two trees for our first night’s shelter. We brought down several loads of supplies from the cars—sleeping gear and food and tools—then we built a fire in the open end of the shelter, hoping that the smoke would rise outside. We ate a meal and huddled around the fire in our sleeping bags, prepared to survive one day at a time.

A little while later, as it was getting to be dusk, a Jeep drove up the trail on the ridge and parked behind our vehicles. We heard a gunshot and looked up to see a man get out of the Jeep. Apparently a visitor from down the road—maybe at the neighboring Ben Delatour Boy Scout Camp—had seen us careening through the wilderness like long-haired Gypsies in our old trucks and junky cars. He saw us as bums and trespassers, and apparently followed us and called the sheriff, because another guy yelled, “I’m the sheriff. What are you doing down there?”

The first man yelled down at us, “Get off this property. This belongs to Pavel.”

Then the other yelled, “This is the sheriff; one of you come up here!”

We looked up the hill at the two men by the Jeep, then we looked at each other.

I don’t know how the decision was made, but Don Winchell was chosen to go. Or he volunteered. Don slogged up the snowy slope from our campsite and talked with the men. He told them that our church had bought the land, that it was legally ours, and that we planned to stay permanently. Even while half not believing this story, the sheriff managed to challenge us: “I’ll bet you don’t last the winter.”

They decided to check on the story. Don got in the jeep with the two guys and they drove a half-mile to the Boy Scout camp. The sheriff went into a house to make some phone calls. I think Don gave them John Roper’s number, or maybe the sheriff called the courthouse or Pavel or someone else. In any case, after a while, the sheriff came back out, got in the jeep, and closed the door. The other guy said, “Well?”

The sheriff looked at him and said, “They own it.”

After Don got back and told us that we were legal for the night, we gathered around what might have been the first fire ever built on that land, drank Almaden wine, and talked quietly as we faded into sleep, cuddled together in our sleeping bags, pioneers in an endeavor that we were confident would permanently plant the Dharma in the West.

Over the next few weeks other people arrived and a few people left. Among the new arrivals were Tom and Jane Ryken, who were to become Rinpoche’s official representatives. The snow melted and we were treated to a beautiful Indian summer. We took advantage of the good weather to build the large main building and personal housing. Tom was the master builder; he was the boss.

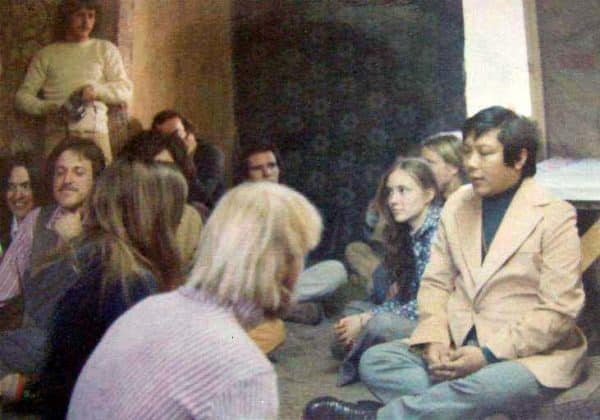

We held meditation sessions in the main building. It had a dirt floor, and dust would rise during walking meditation. One night when Rinpoche was there, we were all sitting on the couches, staring at the shrine with the offerings on it: 5 bowls, a picture, tea, and incense. Rinpoche asked, “What do you do at night?” So somebody went over and picked up the shrine cloth, and folded it back over the offering bowls. Under the shrine cloth was a TV.

Rinpoche said, “Hmm, Buddhism in America,” and we all laughed. This was before VCRs or cable, and we could just pick up one channel from Laramie, Wyoming, which wasn’t far away. So the group of us watched TV with Rinpoche—that evening’s movie was “Children of the Damned.”

Over the next few months, people built their individual cabins, and settled in for the winter. The Pygmies officially disbanded, and each of us was on our own as far as finding food and housing and so forth. Jeff Ellis started a business of making looms, and a relatively modern building was built to house that enterprise.

Parties didn’t happen often, but they were memorable. Rinpoche came up for Thanksgiving dinner in November, and people brought food from Boulder for a feast. We drank a lot, and listened to Fleetwood Mac and the Rolling Stones. Jonathan Eric played guitar, and there was a lot of dancing and consequently a lot of dust. Also that fall, Rinpoche performed a wedding ceremony for Don and Susan Winchell, which was followed by a reception in the main building.

But we spent most days that first winter just getting the fundamental things together for survival: wood, water, and food. Nobody had a decent car, so we often used one to jump-start another. Getting the road cleared was a big deal, and before the well was completed, we hauled water from Rustic, five miles away. Sometimes we practiced, sometimes we worked on buildings, sometimes we drank 100-proof Southern Comfort, or, when desperate, Peter Hull’s Port.

After a few months, the Karma Dzong administration in Boulder started charging us rent to stay on the land. It was just $30 or $40/month, but money was hard to come by. Political tensions arose since we had thought we owned our houses or shares in the land.

Some of the Pygmies left the land that first winter. Others left in the spring. Some of the men got jobs at the sawmill or working for the Forest Service. Eventually, Karma Dzong bought our cabins from us by giving us program credit for the cost of materials.

The loom building was converted into a kitchen, and the first seminar on the land was held in July, 1972—the Ten Bhumis Seminar at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center, RMDC.

This was the beginning of the land of many names, now known as Shambhala Mountain Center or SMC or maybe to some of us, “the land.”