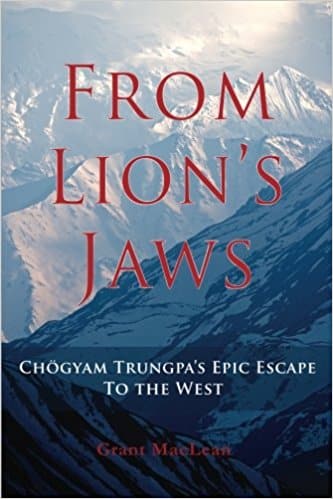

From Lion’s Jaws retells the story of the escape that Rinpoche described in the last part of Born in Tibet. It includes crucial events and material he omitted from the original account, weaves in a trove of survivors’ recollections and adds commentary to clarify the significance of events.

From Lion’s Jaws retells the story of the escape that Rinpoche described in the last part of Born in Tibet. It includes crucial events and material he omitted from the original account, weaves in a trove of survivors’ recollections and adds commentary to clarify the significance of events.

In a nutshell, From Lion’s Jaws book is a form of translation and commentary, reworking the original account to make it more accessible to Western readers. In doing so it casts light on a riveting aspect of Rinpoche’s story and teaching — revealing the story to be one history’s supreme accounts of survival and adventure and also one of its most sublime spiritual sagas.

Unlike Touch & Go, the 2011 video of the escape, which was a scenic overflight of the escape route, the book happens at eye level. On the ground, the story comes to life and we can see the epic in its full power.

While From Lion’s Jaws is a stand-alone work for general readers, for practitioners it can be a gateway back to the original, allowing one to see it with a deeper understanding, knowing it from within as a precious, perhaps unsurpassed, account of meditation in action.

Why retell the story at all?

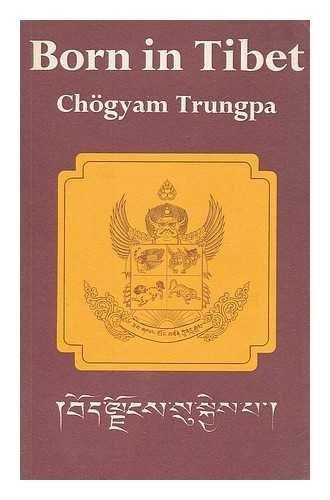

Born in Tibet is an acknowledged classic, an account of ancient Tibet presented by one of its most highly realized and respected lamas. What reason could there be for retelling even a part of it?

Maybe the most compelling was the need to include crucial, highly dramatic material Rinpoche omitted from his original account. There was also the wish to add survivors’ personal stories, to include other voices and viewpoints. These new additions have significantly deepened our understanding of the escape, confirming and elevating the stature of what he and the ordinary Tibetans who followed him accomplished.

But perhaps the most pressing reason to retell the story is that, when we originally read it, few of us really got it, really grasped its power and profundity. Hardly anyone talked about it and, for most of us, the story went off the radar.

Why was this? For a start, Rinpoche himself rarely mentioned the escape, and then only to make a teaching point. Also, in the sixties and early seventies when we first read the book, we were focused on Buddhism and on the extraordinary being who had brought it into our lives.

For most of us the escape seemed to be something of an afterthought. After two or three readings, all I really recalled of it later was snow, mountains, and that they’d had to eat leather to survive. It had obviously been a desperately hard journey, but weren’t all the flights from Tibet like that? I have a faint memory of wondering why Rinpoche spent so many pages describing it …

A form of translation

Then there was Rinpoche’s style o f storytelling. Born in Tibet is radically understated, extraordinarily matter-of-fact. For most of us, this style was unfamiliar, even alien. Unlike Western storytelling, it was almost entirely devoid of drama, free of the dwelling on emotions, feelings, and suffering as a way to boost the drama, empty of all the contrivance of Western writing and movies.

f storytelling. Born in Tibet is radically understated, extraordinarily matter-of-fact. For most of us, this style was unfamiliar, even alien. Unlike Western storytelling, it was almost entirely devoid of drama, free of the dwelling on emotions, feelings, and suffering as a way to boost the drama, empty of all the contrivance of Western writing and movies.

Also, Rinpoche’s original account is often non-linear. Periodically, the narrative digresses to tell lineage stories or inside-anecdotes, giving recognition to teachers and individuals, lovingly celebrating Tibet’s brilliant heritage. It’s a glorious, three-dimensional account— but for those of us used to linear narratives, the storyline could be hard to follow.

Adding to our difficulties, it seems clear that Rinpoche’s collaborator on Born in Tibet, Esme Cramer Roberts, also the editors at Allen & Unwin, may have had a similar experience—thrown off by Rinpoche’s extraordinarily low-key storytelling style. This is most obvious during the escape sequence as Rinpoche describes the myriad difficulties they faced, the seemingly endless ranges of mountains. In the book sentences run on and on in single over-stuffed paragraphs—in at least one case going on for three pages without a paragraph break.

What this meant was that parts of Born in Tibet—notably those covering the escape sequences—are seriously under-edited. This left an enormous amount of work up to readers. Page by page, mountain after mountain, they had to discern where a sequence of events began and ended, and then gauge which events were more important, which more mundane and everyday.

A striking example of Born in Tibet’s under-editing—and the problems it posed to the reader—comes at the beginning of Ch.19, which describes the crossing of the Brahmaputra. Spanning around twelve hours, this series of action-packed events is crammed into one very long paragraph. From Lion’s Jaws, written in a more conventional style, takes around 17 paragraphs to cover the same events.

Such under-editing can lead to a serious misreading. In the Touch and Go video, immediately following the river-crossing episode the narrator states “Only fourteen made it across that night.” It’s a shocking, almost melodramatic, statement—but it turns out to be untrue. In the middle of the long paragraph in Ch. 19, Rinpoche clearly states that fifty refugees had made it to the strip of land near the south bank: and we now know that as many as twenty more arrived later. Yet of the sizeable number of people who saw the video —a high proportion of whom had read Born in Tibet, some several times—no-one seems to have noticed the error. A vital fact had gone missing, buried in the middle of a dense and overstuffed paragraph.

With hindsight, it appears that the warm reception accorded to the Touch and Go video in 2011 stemmed from its bringing home—for many for the first time—the heart-stopping challenge, drama, and danger of the journey, what Rinpoche and the refugees had needed to overcome them.

So in retelling the original story, I had the overriding aim of making it more accessible to readers. First, I chose passages from Born in Tibet that bore directly on the escape, which drove the story; then I rewrote them, blending them into the new narrative. Whenever possible, I employed three-fold logic to help the flow. Finally, I drew out the story’s shape in conventional style, firstly by paragraphing self-contained events or sequences, secondly by organizing chapters around natural hinge-points in the story to allow its intrinsic drama to come through.

These dramatic hinge-points weren’t always obvious, and From Lion’s Jaws chapter organization bears little resemblance to the original’s. In only two (out of thirty) cases do they coincide; otherwise, From Lion’s Jaws’ chapters begin or end at points between Born in Tibet’s paragraphs—or, often as not, in mid-paragraph. So, for example, the new book concludes its Chapter 2 with Rinpoche’s pivotal, heart-rending final departure from Surmang; in the original his departure is described midway through a chapter, in mid-paragraph.

Throughout, I made every effort to uphold the integrity of Rinpoche’s original account, respecting its tone, details and simple, straightforward style. I’ve written only about what we know, steering well clear of the array of modern literary artifacts—including the “artistic license” of inventing events or conversations that might have occurred, but for which there’s no evidence.

Types of commentary

If the reworking of Born in Tibet’s escape sequences can be seen as a form of translation, the retelling also included a type of commentary.

This commentary consisted chiefly in adding newly-recorded recollections of survivors of the escape. Their recollections entirely supported Rinpoche’s account in Born in Tibet, while adding their uniquely personal voices and viewpoints. They also revealed new and penetrating aspects of the original story, often making it even more moving than it already was.

In particular, they added key details of Rinpoche’s leadership, underscoring how truly inspiring he was. They also mentioned events that appear to have been excluded by Rinpoche’s collaborator as being too esoteric, or “magical.” And they told of communications that revealed an exciting, almost cloak-and-dagger aspect to the escape—omitted by Rinpoche from his original account in order to protect those left behind.

From Lion’s Jaws also adds running commentary to enhance the reader’s understanding of the meaning, import, and drama of the escape’s many powerful sequences, and to help clarify or bring out the storyline—the back stories, undercurrents, what was going on.

It highlights aspects of the story whose meaning may have eluded us on a first reading, and which further illuminate our sense of Rinpoche’s leadership—how he led people, how he dealt with dissension, how focused he was on real-world information, and on strategy and tactics. And it sharpens our sense of how hard the journey really was, highlighting the mortal danger he was willing to put himself in to get as many people to India and safety as he could.

Bringing the story home

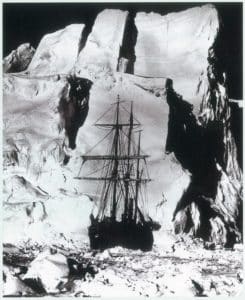

Early on my personal journey of revisiting the story of the escape in the late aughts, it became clear that the journey had been a monumental one. Later, as its outline grew clearer, I became curious about its historical stature. I focused on one that I was familiar with—Shackleton’s famous Imperial Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17, talked of as “one of history’s greatest stories of adventure and survival.”

Research soon showed that, quite objectively, the Tibetan story stood alongside the Antarctic one—at the pinnacle, as one of the world’s pre-eminent accounts of bravery, resilience and spirit. A few readers have gone further, suggesting that the Tibetan story clearly surpasses the Antarctic one in the challenges faced and overcome, and in the qualities of human spirit displayed. About such comparisons, though, we can be confident that Trungpa Rinpoche himself couldn’t have cared less.

We might have known that Rinpoche wouldn’t bother to describe the journey, no matter how arduous, if it wasn’t also suffused with teaching. The remarkable, sublimely human, qualities he and the refugees displayed on the appalling journey are one aspect of those teachings. It was also a spiritual pilgrimage—not just to India, as he proclaimed, but to the sacred land of Pema Ko. The escape was an epic journey, but it was also an extraordinary spiritual chronicle.

For readers with no special interest in Tibet, or in Buddhism, From Lion’s Jaws is a stand-alone chronicle of high adventure and of an epic pilgrimage. For the insightful reader or for the practitioner, it can be something more, a gateway to the original.

With the story’s shape more vivid than it might have been, its peaks and valleys now more sharply etched, Rinpoche’s account in Born in Tibet can open up to reveal a dimension not previously seen. Then the story can be read from the inside, its “radical understatedness” revealing new depths and profundity, the account experienced as an utterly fresh and vibrant portrayal of meditation in action.

Then the story is as it is—one of a mind at rest confronting a tumult of challenges, emotions, drama and suffering, a vivid account of mahamudra awareness in luminous contact with the world in all its aspects, a precious jewel whose lustre cannot be heightened.

From Lion’s Jaws: Chogyam Trungpa’s Epic Escape to the West is available at amazon.com or on Grant’s website which also offers the Touch and Go videos and much more.

The Chronicles has posted two other articles written by Grant as well: Trungpa Rinpoche’s Escape From Tibet: 50 Years Ago and, The Fibre Glass Buddha.