By Grant MacLean

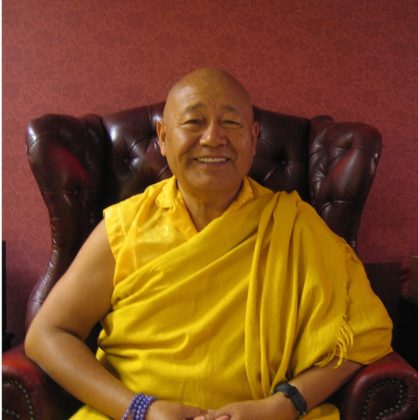

Even for Scotland it was an unusually wet autumn. As I was taking off my dripping cap and rain jacket in the cloakroom of a large, brand-new Samye Ling building, a Tibetan gentleman in a maroon raincoat and shiny red hat walked in looking for all the world like a Buddhist CEO clocking in at the office for a day’s work. Recognizing Lama Yeshe Rinpoche from online images, I introduced myself as the student of Trungpa Rinpoche who’d come to interview him on their 1959 escape. He broke into a great beaming smile and said “I was very close to Trungpa Rinpoche … much closer than I ever was to my brothers.”

His remark sounded the keynote for our time together. In October last year Lama Yeshe had only five days at Samye Ling after a teaching tour and before going into a three-month retreat. Students were arriving daily from across Europe for interviews, he was overseeing an extensive state-of-the-art building project, and his schedule was packed and creaking. He still somehow managed to watch TOUCH AND GO and pass on his recollections when we met, giving us everything he remembered about the escape. But what he really wanted to talk about were his later times with Trungpa Rinpoche in India, Europe and North America.

His personal story is, like that of many Tibetans, a deeply moving one. His given name was Jampal Drakpa, and he’d grown up in Kham in a big valley with two rivers, where the temperature was relatively mild:

“We had apples and many of the things you grow here, so we were in quite a well-off area. Our family was very, very well-off, so there was no hardship. There was no school, so children are absolutely free to play all through the day … it was a very idyllic, very precious experience in my life.”

When he was eight years old, things abruptly darkened for him. On his brother Akong Rinpoche’s way back from Sechen, where he’d joined Trungpa Rinpoche to study with Jamgon Kongtrul, he visited his home and told Jampal that he was to come to his monastery, Drolma Lhakang, where he was to be trained for high office. By itself it was not great news, but local people warned Jampal that it was like another planet there, much colder and higher, where no trees could grow.

And so it turned out. From the moment Jampal arrived he felt utterly out of place, uprooted, unhappy. His brother was a stranger to him, a tulku who, like Trungpa Rinpoche, was taken to the monastery at the age of one or two, before Jampal was born. As a member of the family destined for great responsibilities at Drolma Lhakang, Jampal was not allowed to play with other children and was immediately subjected to harsh discipline: when he was learning the Tibetan alphabet he was forced to shout the letters so loudly that his voice was damaged, leaving a raggedness obvious to this day. Although comfortable and well-fed, he was locked away in a small room above the shrine. He became angry and rebellious. If he’d known the direction of home he’d have run away.

When Jampal met Trungpa Rinpoche perhaps briefly during Rinpoche’s transmission of the Rinchen Terzod at Drolma Lhakang, but fully during the escape he felt an almost immediate connection. Rinpoche, knowing all too well from his own experience what it was like to be a lonely child under a harsh and sometimes punitive regime, was extremely kind and gentle to him. From the start they had a warm, brotherly connection, one that was only to deepen over the years. His telling of the escape’s crisis points during the crossing of the Brahmaputra makes this movingly clear. Their group was marooned on the strip of land separated from the south bank by a backwater. As heavy Chinese gunfire erupted, Trungpa Rinpoche ran across to 15-year old Jampal and a young friend of his, grabbed each of them by the hand and tried to drag them across the backwater with him only to find that it was too deep to cross, leaving them all soaked through, Jampal up to his neck. Lama Yeshe told of other events during the escape, and of his terror during some of the most perilous moments, all of them to be described in my upcoming book (see sidebar), but it was vividly clear that he really wanted to get to the later stories.

In the mid-sixties, Jampal found himself at Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. Again he was the only lay person in the place, again making very heavy weather of it. Under the direct tutelage of His Holiness the 16th Karmapa, he was doing prostrations in a shrine room full of relics of the lineage, from Tilopa and Naropa on, yet he remained edgy and rebellious, and wanted out. Four decades later he joked at how silly he was at the time, laughingly saying: “This guy hasn’t got the wisdom to appreciate it.”

But in 1968 liberation was at hand. Jampal heard that Trungpa Rinpoche was in Bhutan. This sparked an idea, and he asked the Karmapa for permission to leave Rumtek and travel to Samye Ling, in Scotland, to join his brother and Trungpa Rinpoche. Perhaps knowing all too well how that particular venture could turn out, the Karmapa flatly refused the request and told him to continue with his prostrations.

Jampal may have received a direct order from His Holiness, but that was not going to be the end of the story. Shortly afterwards, His Holiness left for Bhutan as the guest of the King taking almost everyone with him except four or five nephews who would be taking care of things at the monastery at Rumtek and who were put in charge of Jampal. Here was his chance, and he had “a clever idea.” When Trungpa Rinpoche visited Rumtek on his way back from Bhutan “I managed to meet him. I said ‘please take me with you.'”

It wasn’t quite as easy as that: the nephews stood in his way. Jampal, though, outflanked them with ease. He requested 14 days’ leave for a trip to Delhi. Perhaps thinking that a break from the monastery in the colorful, sprawling city would help relax their stubborn charge, allowing him to settle more into the life of a monk and into his practice and prostrations, the nephews granted his request.

Getting off the train in Delhi, Jampal headed straight for the Canadian Embassy, where he knew Trungpa Rinpoche was staying as a guest of the Canadian High Commissioner, James George. [Read James George’s account of this time period]

“We used all their facilities to go through checkup and get the passport. They sent a telegraph to the Home Office in the UK requesting permission for me to go there. So with Trungpa Rinpoche’s help I achieved all this in one month usually people had to wait three or four years.”

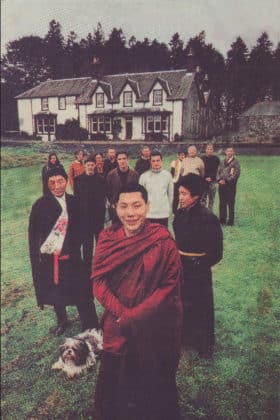

Sprung by Trungpa Rinpoche from his personal jail, Jampal was heading for Scotland. He contacted Samye Ling to let his brother Akong know of his whereabouts and that he’d be arriving there soon (without mentioning that he’d be traveling with Trungpa Rinpoche). Arrangements were made to meet Jampal’s flight at Glasgow Airport and drive him down to Samye Ling.

With air tickets purchased and leave taken from their gracious Canadian hosts, they boarded their flight at Delhi International Airport. Their destination, though who knows how they pulled this off was not drizzly Glasgow but Paris … gay Paree, the City of Light, the home of the Louvre and Maxim’s, the famous Left Bank, Montparnasse, the Folies Bergere, and all the rest. Lama Yeshe had been chortling as he told the story, and now we were both laughing. Between giggles, I asked: “What did you do in Paris” Still laughing, but with a faintly devilish look in his eyes, Lama Yeshe said “Oh, we were just messing around …”

They weren’t done, though. Having had their fill of Paris, instead of heading on to Glasgow and Samye Ling and all that it entailed, they booked a flight to Birmingham. When they landed at the West Midlands airport things took a slightly more serious turn. Authorities took Jampal aside and, with more than a tinge of amusement, told him that he was a very famous person in the UK, his picture to be seen everywhere. He heard later that when he wasn’t on the expected flight landing in Glasgow, Akong Rinpoche and the Samye Ling party became increasingly concerned especially when the airline told them that they had no record of him having boarded the connecting flight. After further enquiries uncovered no trace of him, Akong Rinpoche notified the police, giving them a photo of Jampal which was posted across the UK as an important missing person. After they finally reached Samye Ling following the add-on jaunt in Birmingham, Jampal continued to attend Trungpa Rinpoche, and the two became very close. Today he feels that he is “more Trungpa Rinpoche’s brother than Akong Rinpoche’s brother!”

In 1976 and 1980 Jampal traveled to North America in association with the Karmapa’s teaching tours. Soon after he arrived, he linked up again with Trungpa Rinpoche. He recounts, “When I was in the New York Dharmadhatu, they didn’t like me very much; I was a stranger, they didn’t know who I was …” His mysterious presence wasn’t half of it. He recalls getting very drunk at a large Vajradhatu gathering and Rinpoche telling people to “please take care of my brother.” Dharmadhatus weren’t the only places where his presence with Trungpa Rinpoche was wondered at. “When I went to Karma Triyana Dharmacakra, Karma Tendzin asked me to help make momos, and I took out his sake bottle, and I was so drunk that I broke one of his top plates. This disgraced Trungpa Rinpoche very badly.”

At this point I suggested to Lama Yeshe that he was like a very strong horse who needed good taming, gentle training. He said: “Oh, definitely, but it took me a long time to be tamed.” Having now fully tasted modern Western culture he had become disillusioned with the trappings of materialism and the false highs of hippiedom. “My turning point only came in 1980, when I took full ordination at Karma Triyana Dharmacakra under His Holiness Karmapa.”

At the Karmapa’s request, following his ordination Lama Yeshe and his friend Lama Tendzin helped establish and manage the Karma Triyana Dharmacakra Centre in Woodstock, New York. He received extensive teachings, instruction and initiations from the Karmapa and other leading teachers. In Nepal he also received transmission from Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche on the 49 Day Bardo retreat, a practice which he has since completed three times. Recently the 17th Karmapa said: “If you want to know about meditation, look no further than Lama Yeshe Losal.”

In 1985 Akong Rinpoche requested Lama Yeshe to return to Scotland to continue his retreat at Samye Ling, where in 1989 he became Retreat Master for practitioners in the four year retreat. Then, in 1991, despite his deeply-held wish to remain in retreat for twenty years, he was asked to return to the world to take over the running of Samye Ling. Settled into his new responsibilities he revealed an unusual skill working with marginalized young people, sometimes traveling up to the rough streets of Glasgow to hang out with bikers and the like, some of whom eventually developed a solid meditation practice.

Along with his role as Abbott of Samye Ling, Lama Yeshe now oversees The Holy Island Project, created on an imposing island off Scotland’s West Coast. In 1992 the island was acquired by Samye Ling after its owner, a devout Catholic, told Lama Yeshe that he’d been instructed by Mother Mary in a dream to pass on the “Holy Isle” to him. Originally known as Inis Shroin old Gaelic for ‘Island of the Water Spirit’ the island’s spiritual history goes back almost one and a half millennia, and is the site of an ancient healing spring, the cave of St Molaise, a 6th century monk, and has evidence of a 13th century Christian monastery.

When in the 1980s Lama Yeshe was practicing dream yoga during a retreat at Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, he dreamed of visiting an island he’d never seen or heard of before, a place where human beings and all life forms could live in harmony. The Holy Island Project has allowed him to fulfill this dream, manifested in the establishment of an interfaith Centre for World Peace and Health and a long-term Buddhist Retreat. Volunteers put in years of hard work to repair and renovate the semi-derelict old buildings, while the original light-house cottages at the south end of the island were completely renovated as a long-term retreat for women all of the buildings constructed within clear ecologically-sound guidelines. The main center building now hosts regular courses, interfaith conferences and retreats, while the old light-house cottages were used for the first three year retreat on Holy Island, completed in March 2006 by women from eight different countries.

In line with Lama Yeshe’s vision, and along with numerous bird and plant species, the isle is home to three free-roaming ancient species of mammal. The Eriskay ponies are the last surviving remnants of the original native ponies from the Isle of Eriskay, and have ancient Celtic and Norse origins; the Soay breed of sheep the name comes from the ancient Norse for “sheep” has long existed in isolation on islands off the coast of Scotland, while the white Saanen goats with their large horns and near-smiling expression are thought to have been brought to the island by the Vikings. With support coming in from around the globe, Holy Island has become a model of environmentally-friendly living where humans and animals live and roam in quiet harmony.

The Project has also focused on reforesting the island with native tree species, and there are now 25 different species growing there, including magnificent oaks and beeches and smaller willows and hawthorns, whitebeams, rockbeams, and hazelnut trees; there are also elms, wild cherry, and holly. After planting, the trees are fenced off until they are tall enough not to be damaged by the ponies and goats. Then the fences are removed and new areas reforested.

It’s fair to say that Lama Yeshe Rinpoche has become a well respected Buddhist teacher in Scotland and the UK, and is well-known and admired across Europe. He has attended the European Parliament along with the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, while the walls of his office are covered in photos of him with friends and officials offering a kata to Queen Elizabeth at a Buckingham Palace reception, standing alongside Charles, the Prince of Wales, smiling among a slew of other dignitaries. There are also pictures of him with musicians, rock stars and comedians, including the famously outrageous Billy Connolly, both of them looking as if they’re having the very finest of times together.

Surely, Trungpa Rinpoche would be proud.