At one of the high points in my life, at the tender age of 15, I met Suzuki Roshi at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center in California. My mother, Carol Star Safer, a visionary artist and spiritual seeker, had heard about his monastery from her artist friends. She suggested we go there for a “family vacation!” We were living in Malibu at the time. It was the summer of 1968. On a Friday night, we all piled into the Buick station wagon with my father, David, at the wheel, mother riding shotgun, and my sister and me in the back seat. We wended our way on a six-hour drive through Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo, into Carmel Valley, and finally climbing the long dirt road that led to Tassajara. We arrived just before dawn. My father’s voice woke us up. The first thing I saw was a monk—bald headed and robed—not 10 feet away, striking a gong. It was the most outlandish thing I’d ever seen! As we rolled into the parking area, Dad said matter-of-factly, “I think they need me back at the office.” My dad was open minded, but he knew his limits!

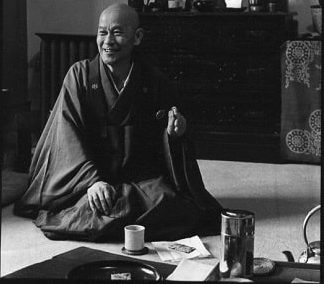

Dad unloaded the car and after making sure we were being looked after, announced he will come back to pick us up on Sunday afternoon. And with that, the family car disappeared out of sight. Later that morning, we were all standing outside among the beautiful trees when a monk pointed out Suzuki Roshi, maybe 20 feet away. He brought us over and introduced us. I was surprised at how short Roshi was. I said my name and extended my hand. As we were shaking hands, I looked into his eyes. They seemed black, and it felt like I was falling in, as in, falling into infinity. That was a first for me, and has stayed with me to this day. I associate that vastness with the “big mind” Roshi talks about in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.

During our stay at Tassajara, I walked around with a copy of The Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha, which my mom had given me, reading snippets here and there. We received meditation instruction and chanted the Heart Sutra with the monks. I took home a copy of the Heart Sutra in Japanese with the English translation underneath: MA KA HAN YA HARAMITA SHIN GYO…It had been printed on a double-sided sheet of thick, high-quality grey paper with a ragged edge. When we got home, I taped this prized chant to the wall beside my bed, and memorized as much as I could.

Besides our meeting, the only other time I saw Roshi was in the zendo—a smallish building with tatami mats on the floor where the monks practiced zazen. I’m recalling eight to ten monks had gathered there, with Roshi seated on the dais. What I remember about his talk, delivered in halting English, is that he said we are fastidious about the way we eat. We put our meat on one part of the plate, segregate the carrots in their own pile—not touching the meat—and the mashed potatoes are piled on their own. Then we proceed to eat, and it all ends up here, pointing to his stomach! His laugh was contagious.

After that weekend, I practiced zazen as best I could through the rest of high school and into university. I received further instruction from Kobun Chino Sensei (later Roshi) of Haiku Zendo in Los Altos and Jiyu Kennett Roshi of Shasta Abbey in Mount Shasta, California. All this to say I was a dyed-in-the-wool Zen student by the time I landed in Berkeley five years later, in 1973. I’m not 100 per cent sure where this took place—either the Berkeley Dharmadhatu or the Berkeley Zen Center. Several of us were seated around a table with Ed Brown. (Ed Brown is the author of The Tassajara Bread Book and editor of Not Always So by Suzuki Roshi). He was telling us about Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche who was coming to San Francisco to teach a 10-day seminar (on The Nine Yanas of Tibetan Buddhism).

“Is it Zen?” I asked.

“No, it’s Tibetan Buddhism,” Brown replied.

“Well then, I’m not interested,” I declared, proud to display myself as a serious Zen student. Ed Brown explained that Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche and Suzuki Roshi were very close, and again urged me to go and check it out for myself. The fact that this message was coming from a senior Zen practitioner wasn’t lost on me, but the clincher was: if this Tibetan teacher was good enough for Suzuki Roshi, he was good enough for me! I went to the seminar—again with my mother—became Rinpoche’s student, and moved to Rocky Mountain Dharma Center (now Shambhala Mountain Center) immediately afterwards. The rest, as they say, is history.