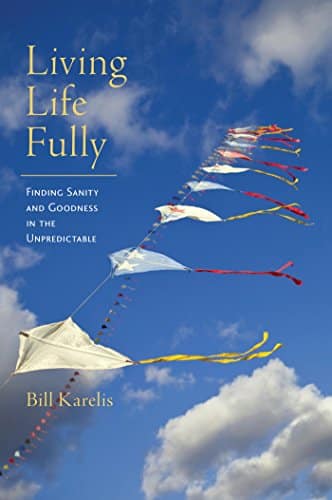

Finding ourselves imprisoned within the four walls of our minds, and then making the journey beyond these self-imposed limitations is what Bill Karelis’s book, Living Life Fully: Finding Sanity and Goodness in the Unpredictable, is all about. This metaphor comes from his 40 years experience as a practitioner of Buddhist meditation and 36 years as a meditation teacher, combined with his efforts to introduce meditation practice to prisoners in the criminal justice system over 16 years. “We learn how we can uplift ourselves,” Karelis writes, “to change our affiliation from neurotic, self-destructive behavior to sanity, gentleness, and goodness.” Karelis’s message echoes that of his root teacher, Chögyam Trungpa, the renowned Tibetan Buddhist meditation master and innovator who also brought the Shambhala teachings to the West.

For anyone who is on this journey “either at the point of first realizing one’s entrapment, or at any point in the discovery of freedom” Living Life Fully would serve as a useful travelogue. Just how the practice of meditation serves as an indispensible tool in this journey is well articulated. Reading this book is like having a knowledgeable guide close at hand. Karelis outlines the meditation technique in the Appendix, and throughout the book explains how this 2500-year old practice facilitates the process of “finding sanity and goodness in the unpredictable.” This includes disengaging from the storylines in our heads, the softening process that comes from experiencing feelings in their own right, and the development of confidence in one’s fundamental intelligence and goodness. His emphasis on unpredictability highlights the elusive nature of reality, beyond one’s control.

A key element of the mindfulness and awareness meditation practice that Karelis describes is letting go. “It could mean that we don’t have to hold on to who we think we are,” he writes, “or hold on to our feelings as identify, or hold on to whatever fixation arises in our mind, merely out of habitual grasping.” Further, he graphically explains: “We can experience our spasm and live through it without validating our progress or attempting to resolve anything.” Shining a spotlight on the mechanics of the meditation technique, he likens noticing a thought to holding a grain of rice between the chopsticks of attentiveness, and then returning to the outbreath. Whereas the mindfulness practice develops precision, he writes, “Insight (or we could say awareness) acts as a further, more profound and vast bridge to the world. It provides a reflection, mirroring the situation, telling us which way to go. If we are about to have a neurotic upheaval, awareness comes to us as a kind of warning signal. It is light but definite. Mindfulness practice quiets the mind to the point where such messages can be distinctly heard.”

While books on spirituality often state or imply that following the prescribed path will result in the achievement of happiness / bliss / peace, Karelis eschews this approach. “If we regard meditation purely as a novelty or a form of spiritual self-reinforcement, whereby we get high on abnegation, for instance,” he writes, “then it cannot cut to the core of ego.” Rather than pursuing one’s agenda—however lofty—he stresses the importance of working with whatever presents itself, with curiosity and a sense of appreciation. With this orientation, one begins to live life fully. Thus, Karelis steers clear of the love-and-light goal-oriented approach that Chogyam Trungpa dubbed “spiritual materialism.”

In his description of the six realms of existence the psychological states of mind that humans cycle through, according to Buddhist understanding, Karelis highlights the dissatisfaction that marks the human realm (hearkening back to the Rolling Stones, “I can’t get no satisfaction”). He states that one’s inability to deal with dissatisfaction is at the root of addictions. Referring to the god realm, he writes: “The gods have it made…because their existence is rife with pleasure and satisfaction; they sit like a cherry on top of the sundae of existence.” This reader, who has read more than a few Buddhist books, finds Karelis’s descriptions refreshing.