When my guru lay dying, I was in Boulder and he was in Halifax, but I had never been closer to him. Every breath he took was another moment of us living together. We breathed the same air. Everybody breathed the same air with him. For awhile.

We had been warned. It had been months since the cardiac arrest that had sent Rinpoche to the hospital the first time. But he had returned home and been breathing through tubes and being fed with a spoon. Some days, rumors indicated that his condition was improving, that he had laughed at a joke or responded to elocution exercises. Other days, rumors had him in an irreversible state of slow degeneration.

A Guru teaches. Guru means teacher. When a Guru is dying, he is teaching impermanence. Why is impermanence so hard to accept? Why does the teaching have to be so painful? I should have known he was dying. I should have known that he was human like me and that he would die like I will.

But I didn’t know. I never thought he was human, and I thought that death was something that happens in the future, or to other people. And anyway, I didn’t care about Dharma at that point. I just wanted to share some more air with Rinpoche.

At some point, the maintenance wasn’t enough; his system collapsed again, and his attendants took him to the Halifax Infirmary Intensive Care Unit. For the next several days, phone calls between Boulder and Halifax kept me up to date. Every bit of information, no matter how trivial, seemed gigantic in importance. He was on a kidney machine or some organ had failed. Or it hadn’t. Something else was wrong or better or different.

But it didn’t really matter. I didn’t know what any of it meant. All I wanted was hope. All I wanted was for my Guru to keep breathing.

On that particular day, I was driving along 28th Street in Boulder, running some errand or another, when my car stalled. I think there was dirt in the fuel line or a problem with the carburetor, but whatever the cause, the engine died on the street, and I coasted over next to the curb and parked it. Maybe it was overheated and just needed to cool off. Maybe.

But for no reason, I thought, “Maybe Rinpoche died.” So after I tried to start the car a few times, and it didn’t respond, I decided to find a pay phone and call Karma Dzong to see if there was any news.

The person at the desk answered my query like he was reading a press release. And maybe he was. “The Vidyadhara, Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche passed into parinirvana at such-and-such a time today, in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was 47 years old.” Or something like that.

My mind stopped. Rinpoche dead? No miraculous recovery? No more hope? “Thank you,” I said, and hung up.

I walked slowly back to my car, through a world that was strangely altered from the way it had been a few minutes before. As I looked around, nothing was quite right. Traffic on 28th Street moved in the same speedy way it had before, but now the speed was pointless. People went about their business the way they had before, but now their business was pointless. They were living in a world without Rinpoche in it. And a world without Rinpoche in it is a desolate place.

But they didn’t know that, those people speeding from stoplight to stoplight. They didn’t know that their speed was too late.

But I knew. Shock sheltered my grief, so I don’t know if my tears flowed immediately. Certainly they have flowed many times since. And as recently as today.

My car started the first time I turned the key.

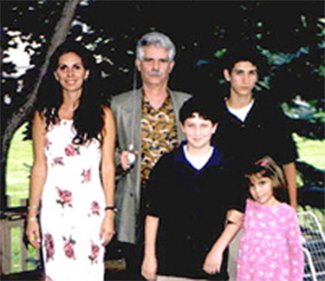

I drove home to my children. I told them that Rinpoche had died. And I know I cried then, and they cried with me. They shared my pain, but they did not share my loss. For I knew what it was like to grow up with Rinpoche in the world, and they did not.

And they did not.