By Bill Scheffel

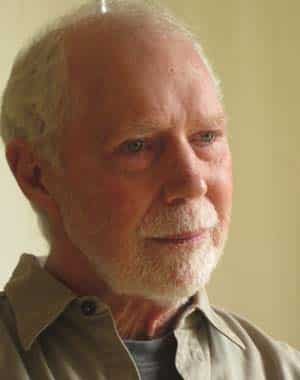

The photograph above shows Eamon Killoran eleven months ago. A few weeks after this picture was taken, Eamon learned he had cancer. In less than a year he was dead. I took the photograph of him in Portland, Oregon, soon after I had arrived for lunch at the home of mutual friends. My first impression of Eamon was his beauty. That a transparency had come to his complexion – as it often does to people well into their seventies. That his beard and his eyebrows were now the same luminous grey. That he smiled with his familiar stature and sense of reserve, but none-the-less, extremely warmly. I had the feeling of falling in love with him, as if in this moment our thirty-six year friendship was being restored, renewed, amplified.

Eamon looked you in the eye and spoke it seemed – with his jaw slightly clenched. His words were typically few, often emerged reluctantly and were astonishingly compelling. On the one hand you felt you had to converse honestly, that his long silences might set you up to make a fool out of yourself or at least display a fumbling frivolousness. On the other hand, what he had to say seemed to come like something out of Melville, a story or confession that becomes enthralling in a hurry.

Over lunch we were reminded that Eamon’s first wife was a member of the Black Panther Party (they had two children together). Eamon loved literature and it was stories like these that made me want him to write his own memoir. Eamon’s father was an Irish cop operating in the more corrupt strata of the New York City police department. One day, his younger brother, barely old enough to walk, discovered their father’s loaded revolver and accidentally killed himself. Alcohol, firearms, gambling. By adolescence, Eamon was faced with the conscious decision to become a criminal or not. As a young man he wandered widely, one day getting a job on a ship. He went on to serve as a merchant seaman throughout his adult life. He understood exactly what had happened on the Exxon Valdez since he had served for decades on similar tankers.

Eamon and I entered the dharma in California, shared countless programs at the Berkeley Dharmadhatu, went to seminary one year apart and became Kusung together in 1980. We waited together, alternately nervous or giddy and with a sense of impending joyous doom each time The Varja Regent or the Vidyadhara was about to emerge from a gate at San Francisco International Airport. We performed the same Kusung tasks: bringing our left arm under the Vidyadhara’s right so we could assist and steady him as he walked. We helped choose suits from his wardrobe and put on his socks. We filled our minds with every detail we could the day’s schedule, its meals, who wanted an interview – before beginning a shift and then spent the next twelve hours in a concentrated free-fall, a near lifetime spent in very awake and orderly chaos of a day (or night) with Chögyam Trungpa.

It was this history, at once long ago and primordially imprinted in my heart that brought me to write what I did after learning by phone, two weeks ago, that Eamon had died:

With his passing I feel my own life evaporate: its traces, the countless sacred impressions and tracks of our gurus, that they literally walked along side us, took water from our hands, even kissed us. These traces are as beautiful, profound and mysterious as the nebula we see through our telescopes. Flaring. Awesome. Where do they go

The living presence of the Vidyadhara’s love carried Eamon on a very steady devotional course. Perhaps spending nearly six-months a year at sea helped keep his remarkable marriage to Michele very alive. It certainly gave him a lot of time to practice and to be very alone with The Vidyadara’s mind and teaching. One might know the way the Vidyadhara loved Eamon by understanding how Eamon loved the Vidyadhara – but who can describe unconditional love If I had to venture a guess I would say it was because of Eamon’s reliability, a particular form of Chögyam Trungpa’s own elemental ethos, the bond he had with all of us: never give up.

It must have been Eamon’s reliability that created a trajectory from his tough, early life, through to the end, his cremation at Shambhala Mountain Center. I was in Boston when I leaned Eamon died and I was not able to attend the event, but our dear mutual friend told me a flock of seagulls appeared out of nowhere when Eamon’s body was removed from The Great Stupa of Dharmakaya in the morning. I told her a flock of seagulls is as astonishing as the circular rainbow that appeared at the Vidyadhara’s parinirvana!

Eamon remained a devoted father to Meadow and Zachary, the children from his first marriage. When he married Michele in the mid 1970s they formed a union and a household that was home to Eamon’s children and to Lucas, Michele’s son from her first marriage. The household became a court when the Vidyadhara stayed there, as he did numerous times. When Eamon and Michele moved to Shambhala Mountain Center in 1991, Eamon began a four-year tenure as SMC co-director, along with Catherina Pressman. Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche selected Eamon for the job and Eamon remained actively involved in the Sakyong’s service and Shambhala Mountain Center for the rest of his life.

Within this outward life of reliable service, Eamon did not seem a man doing things merely because he felt obliged to, even less the follower of a party-line. In late 2003, I spent an evening with Eamon a few months after Michele died. I could feel the world he inhabited; that his home was genuinely at Sakyong Mipham’s service, that he practiced Chakrasamvara sadhana intently, that he was alone and semi-shattered with a diverse stack of books and that there was a bottle of Scotch on the table between us. I felt the challenge, as I always did, of disclosing something genuine as we talked. I felt back-up against the wall by his even more penetrating silences and matter of fact description of what life was like without Michele. I don’t really remember what we talked about, but unlike so many other conversations I’ve had over the subsequent eight years, I remember just what it felt like to be with him, simply spacious and true.

Last fall I began corresponding with Eamon from Istanbul, a city he had spent time in as a young merchant seaman. I wrote about my “psychic crush” not an infatuation, but the way I often felt having my mother and father die in the last three years, as well as having just about every other damn part of my life fall apart in this time. Eamon wrote back, telling me of his own psychic crush:

I think I’ve been living with it to various degrees since Michele’s sudden going. I never really finished packing away her things, just did some more of that recently. Part of that is laziness, inertia, some of it just waiting, living, until it’s obviously time.

He also wrote to me about writing (I was still after him to begin his memoir):

I make small movements towards writing, then get overwhelmed and lastly stopped at the point where I didn’t really know whether I wanted to tell the truth or not. Or try anyway. That movement also keeps getting placed on hold as different dharmic activities demand most of my time, and then and then . . .

From Istanbul I also wrote to Eamon about seagulls (a man who’d seen his share). After living in Istanbul, one can hardly think of the city without seeing seagulls or hearing their cry. I wrote to Eamon, pointing out that as we humans overrun the planet “the animals that remain survivors in our midst seem like analogs, as if a dialog is going on if we could listen or observe more closely.”

When I wrote that sentence, I didn’t really know what I meant by analogs – but a few months later that flock of seagulls appeared above Eamon’s body.