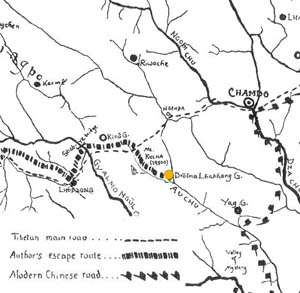

![]() Watch Touch and Go, a documentary on Trungpa Rinpoche’s escape from Tibet and follow the escape route maps.

Watch Touch and Go, a documentary on Trungpa Rinpoche’s escape from Tibet and follow the escape route maps.

As this project is very much a work in progress, please contact Grant if you have any observations or insights about the locations, directions, or routes the refugees took.

![]()

Updates from Grant MacLean: In April 1959, Chögyam Trungpa and a small group of friends and attendants set out to escape from Tibet. After much hardship he arrived in India in mid-January 1960. You can follow Rinpoche’s progress through Grant MacLean’s updates below. Thank you to Diana J. Mukpo and Shambhala Publications for their permission to excerpt the material below from Trungpa Rinpoche’s autobiography, Born in Tibet.

Early December 1959: Preparing to cross the Brahmaputra

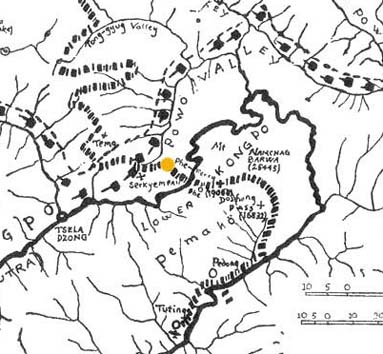

After climbing several more mountain chains, “in the far distance we could see villages and far behind them a snow-covered range which we thought must lie on the farther side of the Brahmaputra.”

They now knew where they were, but there seemed no end in sight. For eight months they’d been traveling through some of the world’s harshest terrain and weather. For eight weeks they’d lived on what supplies they could carry and were now eating their belts and bags. They had begunquite literallyto starve on their feet. Throughout, under a darkening cloud of anxiety and fatigue, they’d shown an almost superhuman courage, fortitude, and good humour. But they were reaching the limits of human endurance.

Now, walking mostly at night and with the point of greatest peril drawing ever nearer, things looked like they were coming apart. After crossing the Serkyem Pass a nun had broken down both physically and mentally; they had no choice but to leave her behind – “a horrid decision to have to take.” And, while there was no way to stop the babies’ crying, the general noise level was rising; some refugees were lighting fires at night, others were letting theirs smoke during the day. Rinpoche again had to be firm, reminding the group that for everyone’s safety the rules must be followed.

Perhaps the biggest scarethe moment when it could have all gone up in smokecame when, as Rinpoche described it “at first light of day we heard the sound of someone walking on the dry leaves; the sound came nearer and nearer. Tsepa had his gun ready; I jumped on him and said there was to be no firing.” The intruder turned out to be a messenger from their own camp.

Traversing a series of low hills and valleys, they saw village smoke and at night heard the sound of voices and barking dogs. They now knew they were close to the river and began looking for a place where the mountains went down to the water’s edge. Struggling through thorny scrub along the ridges they found a spur that dropped away to the river bank that did not come too close to villages.

It was time to build the coracles for the crossing. The folded leather they’d carried from the Tsophu Valley would make two, but they needed more. People contributed leather bags, wood was found and cut, the whole camp joined in and by the end of the day they’d built eight coracles.

Things reached a low ebb on the afternoon of the planned crossing: “…we were very depressed, the sun was hot and we were longing for something to drink.” Then Rinpoche’s attendant discovered that a small bag of tsampa he’d been saving for Rinpoche had disappeared; his suspicion fell on a boy, he lost his temper and furiously chased the youngster through the camp. There was uproar, with people shouting and arguing among themselves. Again Rinpoche had to intervene: “I spoke very severely, for I saw that everyone was on the verge of hysteria.”

Then information arrived from one of the villages that the passes on the farther side of the Brahmaputra were blocked by snow. The news changed nothing. As Rinpoche said: “There was no other solution but for us to go on.”

Touch and Go: November 1959

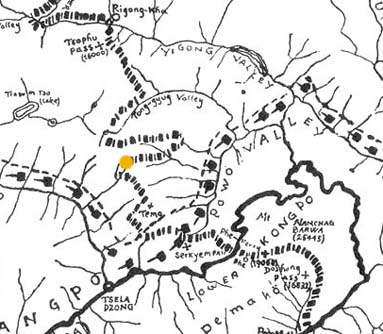

Winter proper had arrived, with its intense rain and snowfalls. As they trekked onwards over towering mountains, along ridges and valleys, through snow, ice and rocks, the going became ever more arduous. They’d been on the road for six months; it had been two months since they’d stocked up with what supplies they could carry. Now, in spite of Rinpoche’s rule that he was to be kept informed of trouble, he heard that people were running out of food and were boiling and eating the leather of their yak skin bags to survive; he was also told that the old man who’d been weakening had dropped dead in his tracks.

Soon Rinpoche’s own food supply ran out. As he too turned to stewed leather, his attendant, feeling that he could not allow his abbott to eat such fare, produced a small supply of tsampa he’d been saving for him. Yet, although everyone was desperately tired, they remained cheerful and ready to laugh, often joining the monks in their prayers and chanting; although they were now literally starving, none of the wild animals that had crossed their paths were killed. For Rinpoche it was a “treasured memory.”

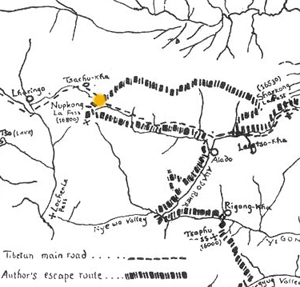

Finally, on the far horizon, they glimpsed the Brahmaputra and, much closer, the smoke from village fires. Fearing discovery, they now traveled mainly at night. In darkness amidst the mist, snow and rainfalls, it was very hard to keep their bearings. Towards the end of November they realised, as Rinpoche wrote, that they “were well and truly lost, surrounded by rocks on all sides; there was nothing left for me to do except resort to tagpa,” a form of divination.

![]() Rinpoche followed the tagpa’s indications. In dazzling sun and snow they came to a high mountain with, beyond it, three more ranges to cross. Beyond them a line of mountains lay directly in their path. As he always did, Rinpoche went on ahead up to scout the way: at the top of the pass he was “amazed to see the Szechwan to Lhasa main road running along the mountainside below, less than a quarter of a mile away.” They were approaching their goal – and the most dangerous part of the journey.

Rinpoche followed the tagpa’s indications. In dazzling sun and snow they came to a high mountain with, beyond it, three more ranges to cross. Beyond them a line of mountains lay directly in their path. As he always did, Rinpoche went on ahead up to scout the way: at the top of the pass he was “amazed to see the Szechwan to Lhasa main road running along the mountainside below, less than a quarter of a mile away.” They were approaching their goal – and the most dangerous part of the journey.

Rinpoche selected a point to cross the heavily traveled road, then briefed everyone: they would approach at night and conceal themselves nearby; everyone would quickly cross the road together; a few men would stay behind to brush over their tracks. Near the road they had to dive for cover as an army truck’s headlights approached; then “I had to be very severe with one woman who, to control her fear, was chanting mantras in a loud voice … ” But they all made it across and soon moved away from the road in the direction of the river. Rinpoche wrote that: “The discipline observed by everybody was beyond all praise.”

Over the months, as circumstances had become increasingly desperate and dangerous, Rinpoche’s role had shifted. From a spiritual master and expedition leader he had – in all but the enmity and violence – taken on the qualities of a general, choosing strategy and tactics according to the terrain and the opponent’s movements while laying down order and discipline. He had done much of the intelligence-gathering and also the reconnaissance work, going ahead to scout the way. Then, traveling at night while maintaining silence, concealing fires, etc. he had revealed the skills of a guerilla commander. Now, when there was the life-and-death need to sharply enforce discipline, he manifested as a drill sergeant.

Underlying it all, and reflected in the extraordinary courage, discipline and good humour of the desperate group as a whole, was the powerful inspiration born of a profound spiritual tradition.

All these qualities were on vivid display as the starving and exhausted refugees trudged onwards. Their moment of greatest peril, the crossing of the Brahmaputra, lay only a few days away.

Days of Crisis: October 1959

![]()

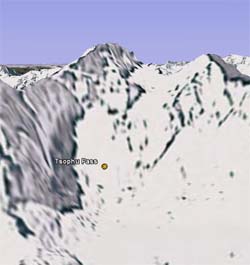

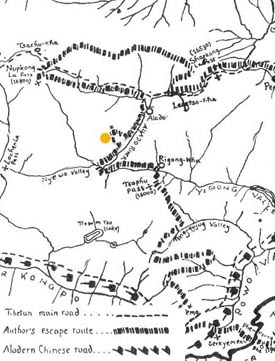

![]() As they approached the Tsophu pass, Rinpoche later wrote: “For the first time I felt a conviction that we were going the right way and would reach India: I was aware of an inner strength guiding me and felt that I was not alone.”

As they approached the Tsophu pass, Rinpoche later wrote: “For the first time I felt a conviction that we were going the right way and would reach India: I was aware of an inner strength guiding me and felt that I was not alone.”

The weather had improved, the guide had finally shown up and the going was fairly easy: the cold had turned the snow into ice, while the pass was not as steep as they’d feared. As they crested the ridge everyone shouted the traditional “Lha Gye Lo!”

They now faced towards India. Beneath them, curving away to the south-west, lay the Tong-gyug valley which they planned to follow until they could cross over the mountains to the Brahmaputra.

![]()

![]() The valley turned out to be longer than they’d expected and, when they finally turned eastwards to make their mountain crossing, they found that the pass was dauntingly steep and the snow so deep that they could only make headway by having the able-bodied men lie prone on it to press it down. Higher up the pass, the weather turned much colder and the track became even steeper. Rinpoche began to worry that the older people, lagging behind, might have to spend the night in the snow but finally, everyone arrived safely atop the mountain plateau.

The valley turned out to be longer than they’d expected and, when they finally turned eastwards to make their mountain crossing, they found that the pass was dauntingly steep and the snow so deep that they could only make headway by having the able-bodied men lie prone on it to press it down. Higher up the pass, the weather turned much colder and the track became even steeper. Rinpoche began to worry that the older people, lagging behind, might have to spend the night in the snow but finally, everyone arrived safely atop the mountain plateau.

Akong Rinpoche, whose group had earlier decided to follow a different route from the Nyewo valley, now re-joined them. Their numbers were now almost doubled to three hundred people and, adding to Rinpoche’s concerns, one of the newly-arrived lamas now began vigorously to question many of his decisions. Then, as they topped a rise from which their guide had expected to see the Brahmaputra, all they could see were further ranges of mountains. They were lost.

Not knowing what else to do, for days they trekked blindly on in harsh weather across a chain of mountains, following when they could valleys that seemed to take them in the right direction. Then, as Rinpoche wrote, “we saw a mountain, its slopes thickly covered with pines: I suddenly felt sure that this was the way to go … ” After a further argument with the fractious lama, everyone decided to follow Rinpoche’s lead. They were all now desperately tired, but Rinpoche himself “felt a strange exhilaration traveling through such wild and unknown country; an inner strength seemed to sustain me.”

It was desperately hard going. Two or three of the smaller ranges could be crossed in a day, but some were so high that it took a full day to cross each of them. Meanwhile, one of the older men, who had eaten all his food, had begun to fail; although everyone’s supplies were very slender, Rinpoche gave him some of his own.

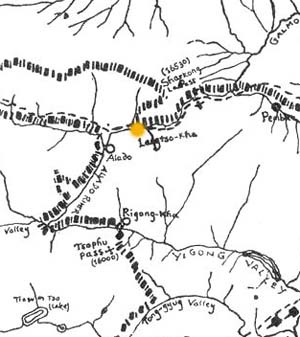

Mid-September 1959: Towards the Tsophu Pass

![]()

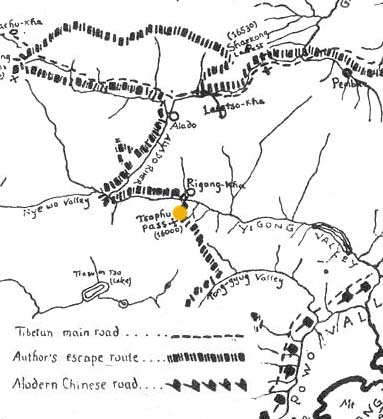

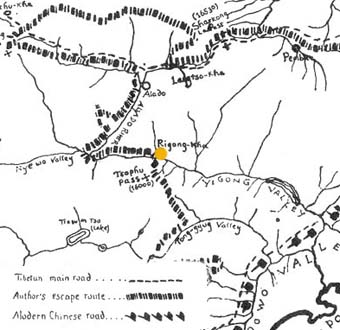

![]() As Rinpoche and his party rested at Rigong-Kha they took stock of the situation. The news was grim. Chinese troops had made their appearance at the eastern end of the Yigong River valley; their plans to follow it until it met the Brahmaputra were dashed. Now they had no choice but to head south, across the mountain wilderness.

As Rinpoche and his party rested at Rigong-Kha they took stock of the situation. The news was grim. Chinese troops had made their appearance at the eastern end of the Yigong River valley; their plans to follow it until it met the Brahmaputra were dashed. Now they had no choice but to head south, across the mountain wilderness.

They re-crossed the torrent, hauled one by one along a thick hemp rope by men on the far bank, then headed up into the Tsophu Valley. To add to their mounting worries, as Rinpoche wrote, “the weather was breaking up with frequent storms. It was likely that there would be a lot of snow on the passes … “

They’d sent out appeals for someone to guide them across the mountains. While they waited in the cold for the guide to appear, Rinpoche went into a short retreat while the camp prepared for the journey. People had been exchanging their possessions for food, especially dried meat and tsampa; now they repaired their boots and clothing and were organized into groups, each with a leader. There’d also been a head count: Rinpoche was shocked by the numbers – about 170 people “among them men and women seventy and eighty years old as well as babies in arms, but very few able-bodied men.”

He decided to brief them on what lay ahead. He told them that conditions would be very hard and difficult and that they would not be able to stop for anyone who became ill or exhausted. After taking the few days to decide that Rinpoche had insisted on for people to think it over, all still wanted to come. He then laid down rules: if attacked, no one could kill Chinese troops; there was to be no stealing or disunity, and he was to be immediately informed of anything that went wrong.

Rinpoche repeated a plea he’d made earlier for everyone to eat sparingly of their precious supplies – a plea which many had quickly forgotten – and then told them: “Our journey to India must be thought of as a pilgrimage; something that in the past few Tibetans have been able to make” a journey to the land where the Buddha’s blessings remain. “It is fortunate for us that our journey is hard …” for the rewards would be the greater. He reminded people to not be concerned about external enemies, but should each moment be aware of destructive forces from within, and that “… each step along the way should be holy and precious to us.”

They’d hoped that a guide would reach them by September 13 but none had appeared. Rinpoche decided that they could wait no longer. After sending men ahead to clear the way to the pass, he and the group of courageous Tibetans climbed up into the snow line.

Mid-August 1959: The Bridge to Rigong-Kha

Rinpoche emerged from retreat into a flurry of rumors about Chinese troop movements and a forceful argument about what to do. But he was now clear: their destination must be India.

He led the group southwards down an exhausting 9,000-foot descent from the cold and the prowling bears of the plateau into the fly-tormented heat of the Nyewo Valley. Akong Rinpoche’s party had meanwhile decided to try a separate route, over the mountains.

It was clear by now that Chinese troops were encroaching from all directions. Rinpoche decided to head eastwards along the Yigong Valley, choosing to brave the uncertain prospect of crossing a river in full spate and the struggle along a steep ravine. While they began to build leather coracles to cross the river they sent away the horses, mules, and yaks which for three months had carried them and their supplies. As a high lama Rinpoche was unaccustomed to walking and he wondered how he would manage.

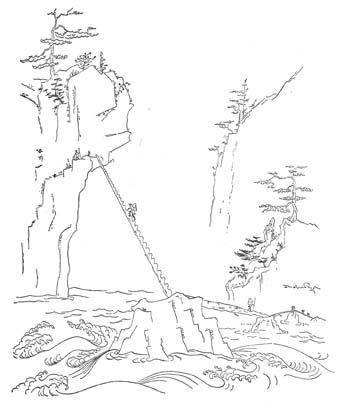

![]() The closer they came to their next objective “the worse the track became, till we were faced with a very high cliff coming right down to the river.” The way ahead was horrifying. First, they had to clamber up the cliff face using bits of dangling chain for handholds and little cracks in the rock for their feet; then, after clambering onto a narrow ledge over a sheer drop to the river, they had to climb down a long “ladder” – notched pine trunks lashed together – to a rock in the middle of the torrent; further logs reached across to the far bank. Helped by porters, in the end, everyone made it across safely.

The closer they came to their next objective “the worse the track became, till we were faced with a very high cliff coming right down to the river.” The way ahead was horrifying. First, they had to clamber up the cliff face using bits of dangling chain for handholds and little cracks in the rock for their feet; then, after clambering onto a narrow ledge over a sheer drop to the river, they had to climb down a long “ladder” – notched pine trunks lashed together – to a rock in the middle of the torrent; further logs reached across to the far bank. Helped by porters, in the end, everyone made it across safely.

Although further steep and scary climbs of 1,000 feet or more followed, none were as terrifying as the first, and they soon reached the village of Rigong-Kha where they rested for two weeks.

July/August: Plateau Above Alado River Valley

![]()

![]()

Following Rinpoche’s decision to head southwards and await developments, the escape party had made its way over the high pass of Nupkong and down the Alado River valley. Here the main road was thronged with refugees, the air putrid with the smell of animals dead from starvation.

Leaving the road they had struggled up a series of dangerous mountain trackslosing at least one horse down a precipitous cliffand found themselves on a broad plateau. There they tried to glean what information they could from other refugees, but the situation remained murky and chaotic; no one had a clear idea of what was going on, of what to do, of where to go. While Rinpoche’s mind remained fluid and open to events, the idea of an escape to India now took on a more vivid form. He enquired from local travelers about possible routes across the mountains but was assured that it was impossible at this time of year.

He felt that it was necessary to replenish his strength for what lay ahead. After a short but perilous mountain trek, they found a “nice little open valley” where they set up camp. There, as large brown bears occasionally killed and ate their animals or foraged around their tents as they slept, Rinpoche went into retreat.

Further updates from Grant on Trungpa Rinpoche’s escape from Tibet throughout the year.

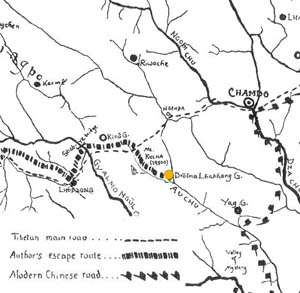

Late June/early July 1959: Turning south toward India

![]()

Eastern Tibet, late June/early July 1959: Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and party, having regained the main road towards Lhasa after crossing the highlands from Langtso Kha had heard from travelers that Chinese troops strictly guarded the road towards the city.

They could not continue their journey westwards but had no clear idea what to do. Then they received the news that His Holiness Karmapa and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche had escaped to India. Rinpoche made his decision: “Since we knew that we could not stay where we were, I decided that we must continue southwards at least for a few months, and by that time we would know more about the state of affairs in Tibet.” [p. 181] From this decision all else followed.

Further updates from Grant on Trungpa Rinpoche’s escape from Tibet throughout the year.

June 1959: Impasse at Langtso Kha

![]()

Fifty years ago, in June 1959, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and party reached an impasse at Langtso Kha. Unable to progress further, for the time being Rinpoche “began to work on an allegory about the Kingdom of Shambhala and its ruler who will liberate mankind at the end of the dark age.”* During the remainder of the escape, this allegory, which is the first known reference to Shambhala in Trungpa Rinpoche’s writings, grew into a two-volume epic which was lost as the party was crossing the Brahmaputra River into India.

April 23, 1959: No choice but to escape

![]()

![]() On April 23, 1959, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, along with a small group of friends and attendants, set out on his journey from Tibet. The journey became an epic one, its outcome of vast importance to the spread of dharma in the West.

On April 23, 1959, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, along with a small group of friends and attendants, set out on his journey from Tibet. The journey became an epic one, its outcome of vast importance to the spread of dharma in the West.

By early 1959, unrest was spreading across Tibet. Lamas and monks, whom the authorities thought were behind the unrest, were being rounded up, and sometimes shot. The well-being of such an eminent teacher as Trungpa Rinpoche was in obvious danger. At his advisors’ request, Rinpoche went into hiding near his friend Akong Rinpoche’s monastery, Drölma Lhakang, where he had been teaching. As the tumult spread it became clear that he had no choice but to escape. A monk approached Rinpoche to ask his intentions so that he could make preparations to leave. In Born in Tibet, Rinpoche describes the encounter: “He wanted to know the exact date on which he should be ready. I told him at the full moon, on April 23rd. This was the Earth Hog year, 1959, and I was now twenty.”

He continues a few pages later: “Until the 22nd I remained in the village and then set off at night for Drölma Lhakang, which I reached at six o’clock the next morning after a roundabout journey avoiding villages, while a tremendous snowstorm was raging … We started with a tearful send-off from all the monks of the monastery.”