Interviewer: Jeff Wigman

JW: Why did the Vidyadhara create a new way of making thangkas?

JN: Because we live in the West, and he wanted to make thangkas that sort of fit into the Western look—fit into the Western mind. When you look at something like a Tibetan thangka, you see it as a cultural artifac—something that belongs in a museum rather than something that is living. Rinpoche was trying to develop a whole look for Buddhism in the West, because the West has a different scale and different materials. So he wanted to use Western scale and Western materials and a whole Western look to do that. So, he wanted it to be contemporary, living.

JW: Was it just an East / West thing or did he see this going back, like…

JN: Yeah, he said that the thangkas in Tibet had really lost it [laughter]. But he really totally admired Gandharan style, which was happening in India around the time of emperor Ashoka. He loved how simple and powerful the geometry was, of not just the shapes, but the forms, the volumes, and the sculptures, and the volumes in the temples. He loved the monumental scale of the sculptures. He also loved the fact that the Gandharan style was developed by Greek sculptors living in India that became Buddhists–or at least were hired to do the Buddhist thing. They knew a lot about the geometry, called the thigses (thig tshad), and Rinpoche loved the monumental scale of their work.

There were certain classic eras in thangka painting that he just loved. There was a time when things had been sort of simple and monumental. When you looked at a representation of the Buddha, it felt like it was 10,000 miles high. It just had a certain sense of scale to it, and simplicity and power. So he actually was wanting to return to that era. He thought the Tibetan approach had become too lyrical, too flowery, too pretty, too sentimental, and that wasn’t the way he was [laughter]. So I think he wanted to have thangkas that were like him, come to think of it—powerful and gorgeous and simple, but really pure, like going back to the pure teachings and getting rid of all the unnecessary ornamentation.

JW: What do these thangkas do that traditional thangkas couldn’t do?

JN: Well, the really early traditional thangkas could do it. But the paintings we were doing—since the geometry was so pure, and he understood perception so well—sort of fit into your eye, like a key into a lock, in a way that was much more powerful than all the thangkas that were being done in Tibet. In Tibet there was a tradition of this kind of geometry, but people had forgotten what it all meant, and what it was supposed to do, and they just imitated it. So it still kind of worked.

Trungpa was going back to perception—how perception worked. He was designing these thangkas to fit into your eyeball. He even said at the time that the Buddhist symbols are actually woven into the retina of your eye—llike the eight sacred symbols are actually woven in.

I actually remember asking him, “Uh, well, there were human beings around before Buddha and the eight sacred symbols, so how does that work?”

He said, “Well, Buddha traveled backwards in time and wove it in [laughter].” You know… you can see these things every now and then if you smoke the right thing or drop the right thing.

So we talked a lot about how perception works, how the rods and cones of your eyes are put together. He wanted these thangkas to fit in really cleanly, so they really connect with you on a neurological level, beyond thinking. It would just go right into your brain and sort of bypass the whole conceptual process. That’s how you could say they’re different. But again, using Western scale. In the past, thangka painters really knew how perception worked. The yogis had techniques to experience it, like pulsing blood across their eyelids with their eyes closed facing the sun so they could see the geometry of their eyes.

But those thangkas don’t work anymore either because we have a different scale. Our buildings are at a different scale; our bodies are at a different scale. You know, everything around us has our sense of scale, so those old thangkas don’t fit in either, even if they are very pure. It’s like we’re speaking a different language. So you have to constantly keep it fresh and invent it new. And that’s another reason why Rinpoche wanted to use Western materials, like acrylic paint and staining canvas—something nobody would ever dream of in Tibet. We’re used to looking at certain materials and then when you put the thangka up in a room, it’s going to be a Western room. And he wanted the scale and materials to match the room, to vibrate harmonically with the room, whereas a Tibetan type of paint and Tibetan scale wouldn’t. It’s always going to be other, always going to be cultural artifacts on the wall. OK?

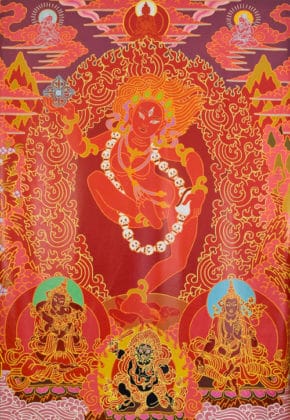

JW: Could you describe the major differences in technique?

JN: OK, he did it by really making it into sort of a pure dharma, but all dharma in the end is talking about your mind. So the thangkas that he came up with are reflections of how our minds actually are constructed. So for instance, starting out by staining the canvas all one color-not gessoing it at all, but actually taking raw canvas and staining it with this chemical we had that you can add to acrylic paint so it can penetrate the fibers—that created the dharmakaya, which is the emptiness aspect of our minds—that our minds are essentially made up of emptiness. So, there’s Buddhist teaching there. And in visual dharma, staining the canvas would be the equivalent of dharmakaya or the emptiness aspect. Then the second stage would be putting the outlines of the deity on in a contrasting color. And the outlines would be completely classical. You don’t mess with the outlines. You don’t mess with the deity. You don’t change any implements. You want the scale to be exactly according to the thigses that were worked out. And the outline of the deity is like the sambhogakaya, the energy level, the speech level that arises spontaneously out of the emptiness. And so just having this kind of electric outline in this very contrasting color–the first one we did had a deep blue background and then a reddish orange outline, so it’s very electric, like an energy, like sambhogakaya–it’s not real, it’s not a solid thing, it’s an electric-field-energy deity.

Then the next stage would be to add variations on the color of the background and variations on the color of the outline, but then making really contrasting colors to both of those colors. By doing all that, it made everything more solid, and things become more differentiated in the forms and the backgrounds. And then we’d even put in some shading and everything. And that was like the nirmanakaya. It was like joining the two together—joining the dharmakaya emptiness and the sambhogakaya display of luminosity, which is the union stage. So all of this is dzogchen, I now realize—even as I’m speaking, I’m sort of realizing this. After you do the outline, that’s what you do. He said, “Put in variations of the blue,” let’s say. And then variations of that reddish orange and then put in completely contrasting colors like some greens, you know. Red, blue, yellow, green. And that brought it down to earth and made it look like a full-blown image that you could totally relate to. So he was not only invoking–the thangka is like a portrait of your mind; that’s the way your mind works. The emptiness, the luminosity, and then they’re joined together to create the world, the nirmanakaya. So he was actually creating a style of painting that was a reflection of your mind. That’s how they’re different. Was that the question?

JW: Could you describe the approach to drawing the figures—what the figures were meant to do differently than the other paintings we were looking at?

JN: He wanted the figures to be the thing you see when you look at it. He wanted you to see a deity that basically seemed to be a real form—a three-dimensional form. And deities are supposed to be forms that are hollow and filled with light. So he didn’t want them to be anatomically correct, with muscles and sort of illustration-style. It was supposed to be pure volumes—spheres and cylinders and cones–that kind of thing. The figure would seem to be made of these pure three-dimensional shapes that are joined together as I said, as opposed to a real human being with wrinkles and muscles and sinews. So the Buddhist deities are stylized or idealized volumes in space, because the volumes of course relate to shapes, and the shapes go into your eye. When it gets translated in your brain it has to go back to being volumes. Because the idea was to picture a deity. That’s what these practices are about. You visualize a deity in front of you, then you visualize yourself as the deity, and the deity is always supposed to be seen as hollow. You know, a hole in space. And again this gets back to Trungpa’s teaching that space is solid and forms are hollow. So when you saw the deity in a thangka, he wanted you to have a real instant sense of three-dimensional hollow form so you could visualize that in front of you and visualize yourself as that. And the Tibetan thangkas had degenerated into a bunch of gestures, and learned language, and you certainly didn’t have any sense of form in a lot of them. And on the other hand he certainly didn’t want it to look like anatomy lessons.

JW: You were describing that some of the forms were simplified. I was wondering what was dispensed with-what he saw as inessential?

JN; Well, when you have a fluttering scarf, how many flutters do you need in it to invoke the idea that it’s fluttering? You really only need one or two little twists and flutters there. But the Tibetans had just heaped flutter upon flutter upon flutter. Part of this problem with the thangkas is that thangka painters weren’t always religious monk types. They were these bands of gypsies that went from monastery to monastery. And they got paid by the deity [laughter]. And the longer it took, the more money they got. So that’s why thangkas are sometimes crowded with tons and tons of deities–because the painters are getting paid by the deity. And the other way of paying them was that you had to constantly have parties for them and give them cool presents to inspire them, and give them lots of chang. So, the thangka painters weren’t real practitioners. Every now and then a famous guru would have some vision or get into thangka painting. One of the early Karmapas came up with a certain school of thangka painting. There were always things like that, but by and large they were more like gypsies. So people wanted lots of brocades and gold and wanted the thangkas to look a certain way. They didn’t really care if it looked like a deity. They weren’t really concerned with “Can you visualize it?” because they weren’t doing the practice. They were craftsmen. And it was easy for it to deteriorate into just making pretty pictures.

JW: How many of these did you make?

JN: I only made six of those. An Avalokiteshvara-the first one-was 4 foot square, and Trungpa actually had it on his shrine for a couple of years in Four Mile Canyon when he was first living in Boulder. And then there was Vajrayogini, which still is up in Nova Scotia at one of my old girlfriends’ house. And an eight-armed semi-wrathful Black Tara—that was one of the last ones. That’s at my sister’s in New Jersey. There was also a yab-yum. I was trying to paint one for each Buddha family. So Avalokiteshvara was blue. Vajrayogini was red, and Yab-yum was kind of ratna. And Black Mahakala was karma. I forget what else.. At any rate, the last one was a giant Buddha-white, huge. It was maybe 6 foot square. The last I saw it was hanging at the barn in Karma Choling completely covered in these streaks of bird shit–pigeon shit–that were actually almost—a very cool grid-like thing covering. Kind of Jackson Pollock meets Buddha. At any rate, Trungpa loved Jackson Pollock, so it didn’t offend me. But otherwise, I don’t know what happened to the rest of them. Various girlfriends have them.

JW: How were they received?

JN: At the time it was in the early 70’s, it was like, “Whoa! What’s he doing? How come he gets to paint pictures all day and we have to do all this shit rota and clean the house? What’s with him? And he’s on acid all the time anyway.” You know? So they were received kind of like “Whoa what the hell is that all about? I guess it’s kind of cool.” Nobody quite knew what to make of them. So they didn’t really catch on. People would come in and see Trungpa’s shrine, but people wanted the old-style Tibetan things. On the other hand, I heard that recently at a fire puja up in Nova Scotia, my friend who has the 4 foot by 6 foot Vajrayogini brought it to the Vajrayogini fire puja. And she said people really got off on it—really loved it because times have changed and I think most people are maybe getting a little tired of Tibet, you know? [laughter] You know what I mean? I mean, come on! It’s the dharma you’re interested in. But Tibetan culture has been so mixed up in it. At any rate, she told me that people totally flipped over it, and that was the first time anybody has seen it since that period when I was painting them. I haven’t. Nobody’s seen them [until now].

JW: Did the Vidyadhara expect that people would continue making thangkas in this way?

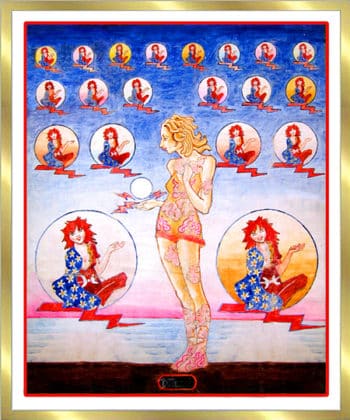

JN: Well, yeah. He wanted to start a whole new style. At the same time that we were doing his thangkas, I remember building furniture that he had designed that came from Tibetan inspiration, but again was totally Western scale–furniture that fit into a modern house without looking like an antique. It would look like modern furniture. Really cool stuff. All the furniture he had designed was inspired by nomads. He thought all furniture should be very transportable, because nomads moved around all the time, and he said Westerners move around all the time. So, the idea was to make furniture that’s movable, as opposed to the Victorian giant chairs that you can’t get through the door anymore. And so we were designing clothes and jewelry and a whole look. The formula for the look, which I finally got out of him, was: a Japanese sense of space; a Tibetan sense of color and ornamentation; and a Western sense of scale and materials.

So the Japanese sense of space is very asymmetrical, as opposed to Tibetan space, which is very symmetrical. He wanted to have this asymmetrical space. And the Japanese sense of space is also very sort of neutral color—white or empty or beige or natural colors, that kind of thing. But then he wanted to have these hits of bright ornament and color—Tibetan style. He took a Tibetan thangka and he hung it in a Japanese room with tatami mats and screens-that kind of thing. But then taking both of those things and doing them fresh in Western materials and Western scale. So he came up with this whole thing-I mean, in the early 70’s that’s all we talked about. That’s when we wanted to have guilds, and then there was the first shrine… Now, interestingly enough, the first shrine has reappeared—just a crystal ball and a book and some bowls. That was the first shrine in 1970. He described it as a dzogchen, a Maha Ati shrine. And since Maha Ati is dharma art, we always thought of it as the dharma art shrine. Why else would he have done it? Of course he wanted this style to take off. He wanted this to be the new look for everything. But… [laughter]

JW: That was my next question. It hasn’t happened.

JN: No, it hasn’t happened. Trungpa realized, I think somewhere in the mid 70’s, that artists just weren’t buying into it. Everybody still wanted to do their own thing and work and do modern art according to what else was in the galleries and the concert halls so that they’d be up with their peers, and nobody really wanted to change what they were doing and start this style, which means you have to become kind of selfless. Take Art Deco, for instance: it means adopting a style that other people are doing. Whereas with modern art, everybody’s supposed to be radically different from each other. You’re not supposed to look like anything that your neighbor is doing. He realized that wasn’t happening, so he started to manifest more and more traditional ways anyway, because he realized that he needed to do that to connect with people—that in the beginning, he could be walking around in jeans and a t-shirt and hang out with everybody and do all this crazy art stuff, and that was the only way to break through to people’s consciousness. What was the question?

JW: It hasn’t caught on.

JN: Oh, it hasn’t caught on. Yeah, so the whole art thing was just … Trungpa taught in reverse way. He started by teaching dzogchen. Then he taught the pure Vajrayana; if you read the transcripts of ’73, ’74, ’75, they’re just mind-blowing. And then he started laying the groundwork-more Hinayana, Mahayana. And then he finally got it all organized. We had to do a lot of Hinayana practice–dathuns and all this stuff. But it was all done backwards. Yeah, it didn’t catch on, because a lot of the students, most of the students—I guess the artists wanted to do their own thing. And then the more scholarly people started finding out more and more about Tibetan Buddhism, and they wanted to learn about all the … they wanted to be traditional. And they wanted to do traditional practice, and they wanted their shrine rooms to look more traditional. And they wanted their teachers sitting on thrones wearing robes. And everybody wanted everything traditional, and then all the thangkas were just the same old traditional thing.

You know, we still have our sense of style in our shrine rooms–the big space and the big bold scales, but that’s just leftover imitation from Trungpa’s days. Because everybody knows it’s cool looking and it kind of works—our shrine rooms are really great compared to those other guys’ shrine rooms that look just too imitate-y Tibetan—too, too claustrophobically Tibetan. They didn’t catch on … yet. Maybe they will. But it’s going to be when people want to get together and create a look, a style, a new culture. If you want to rule a kingdom, you have to have a kingdom, and a kingdom is a culture and a culture is art. And art isn’t just borrowing stuff from the past, but we seem to live in a nostalgic time in general these days. There is no culture in America either. There is no vision going on in the art world or anything. It’s all retro, and even in movies–everything is retro and nostalgic, and so it seems to be a universal problem. On our scene and in general in the West as well, there was no real look. There is, sort of—but hodge-podge. There’s no vision-forward style thing going on.

JW: I think you just gave another controversial interview.

JN: Oh. Could have been a lot more controversial. So is that it? Any other questions?

JW: Not offhand, unless you want to add something.

JN: I’d love to say that it’s all waiting there, that usually dzogchen comes at the end, but Rinpoche had it at the beginning, so maybe we can do things correctly and have it at the end. Early on, he said in order to have an enlightened world, it has to look enlightened. He said all those other cultures had a look. Japan has a look. China has a look. Tibet had a look.

Greece had a look. Egypt had a look. These cultures were like enlightened cultures and had a cool look, you know, that everybody agreed on. So it wasn’t just this hodge-podge of different things. That’s when he said that, in order to be an enlightened world, it has to look enlightened, which means you have to design all the objects in it to be from an enlightened point of view. And he said [his] idea would be if we sold stuff in K-mart, so it isn’t like exclusive, one of a kind, or chic, or really expensive, but mass-produced K-mart. And he actually mentioned bedsheets. So why couldn’t we design a bedsheet that has our feel, this energy–cheerful bedsheets that wake you up. Maybe that isn’t a good idea; you’re supposed to go to sleep with bedsheets. But, at any rate, that was the level, and he actually mentioned K-mart and mentioned bedsheets as his ideal. He said when we’re selling things in K-mart, we’ll know we’ve succeeded. We’re on our way.

So the only way people can learn this—they’re certainly not going to study classic Buddhism and Shambhala. It’s just too lengthy and expensive and too foreign, too ancient. But people can at least learn the principles of dharma art and see that it’s a reflection of your mind and it’s completely natural and clear, and the essence of what has happened throughout history anyway. People intuitively have done this forever. And it’s cool because it’s uplifting and it’s cheerful. And it’s beautiful—a word that you don’t hear much in the pop world. And it could still happen. But people can learn the principles without becoming Tibetan Buddhists or Shambhalians. And principles alone are a path. At any rate, it’s still waiting there. The whole world—look at any kind of art criticism—it’s just how sucky everything is, and everything is just retreading the same old thing. Everybody’s just doing endless variations of the same old stuff. The culture in movies—everything is not going anywhere; there’s no vision. The last time there was any vision probably was in the 60’s, and before that in the 40’s, and the 30’s. Trungpa used to say in the 1920’s things were really waking up and there were great things going on. But everybody knows what it means when there’s a common world vision, and I don’t know if gangsta rap is it [laughter]. That’s exactly our idea of baggy pants and you know, whatever. So it still can happen and I think loads of people want it to happen. It’s just funny that Western Buddhists are still wanting to be traditional, and, Western culture is basically nostalgic at this point. So, anybody want to sign up? Help!

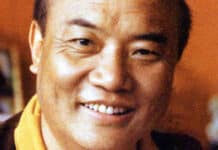

Among the earliest of CTR’s students in North America, Jack received a wealth of first-hand dharma art instructions and helped create many of the visual elements of Trungpa Rinpoche’s presentation of dharma in the West. He taught visual dharma at Naropa from 1974 to 1979. In the 1970s and 80s, Jack and renowned model Sara Kapp applied dharma art principles to the world of fashion and modeling. Jack Niland is currently a freelance artist, designer, and raconteur living in NYC. In September 2008 at a community meeting at the New York Shambhala Center, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche and the Sakyong Wangmo, Khandro Tseyang, presented Jack Niland with a proclamation and the title Artist to the Kalapa Court, The Kingdom of Shambhala.