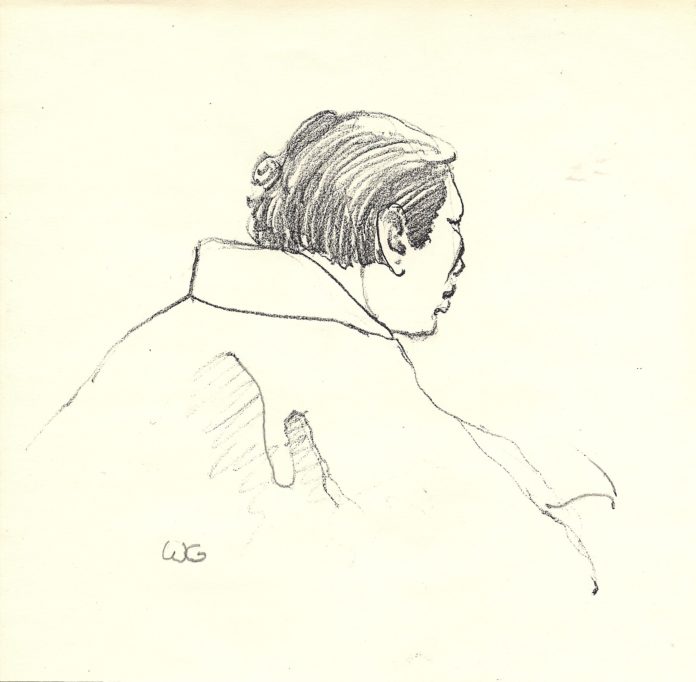

I met Rinpoche in 1971, becoming a student of his soon after, and for life. During the course of it, he assigned to me an eclectic array of different tasks and challenges. One of these was to make portrait sketches of him as he went about his business of the moment. Typically, I would get a summons, sometimes when he was delivering a talk nearby and it was easy to get to him, but he didn’t hesitate to telephone from, for instance, Colorado, putting me on an airplane at short notice. Military venues were costumed with uniforms, many kinds; lectures were mostly suit and tie; for a bedroom event, messing with my mind, he wore nothing at all; for a session during which he made calligraphy, he wore Zen robes and his hair in a Japanese topknot.

This was his costume when I sketched my favourite of all the drawings that I made of him. I discarded a lot more elaborate attempts than I kept, but this particular little two-minute, unfinished toss-off was a happy accident and a keeper for sure. At the time, I couldn’t wait to show it to him. His usual reaction to my work was to examine it piece by piece in stony silence, acknowledging things only with an inscrutable “Hmmm,” nothing else.

Handing him my proud little drawing, I hoped for a less lethargic response this time, maybe even a tickle of praise, although I was braced for any kind of criticism. Line work, style, composition, all were open to it, hopefully something, anything. He studied the picture for a while.

“Hmmm” came his inevitable comment.

Only much later did his reviews start to come in, and they were all carom shots bounced off sangha chums of old, never directly to me. “He told me you’re the only artist who ever captured his essence,” reported a grinning old student who had written down the quote. Then the same message trickled in from other sources, bathing me in warm, molten honey in a way that no doubt would have wrinkled my teacher’s nose.

Thereafter, I framed my remaining pictures—those I hadn’t given to friends or discarded for lack of merit—and hung them through the house. Most prominent was the quick calligraphic little sketch that I had liked from the beginning. Quite shamelessly, I had fallen in love with a piece of my own work. For one thing, it reminded me that whatever expected art lessons I hadn’t got were in my dreams, and my teacher’s intended instructions were in modelling, not drawing. Or so it seemed. He never told me that, but he demonstrated it throughout every meeting, talk, whatever the session, by taking a comfortable pose at the outset, and returning to it, like the out-breath after every diversion. While he was gesticulating, talking, shifting, I had time to fill in the static details while waiting for the foundational pose again. Unlike the unstirring model of a figure-drawing class, or the rigid subject of a formal portrait, this model was always animated, never static, yet reliably back where wanted for the portrait’s sake. Lessons to be sure, I reflected, looking at my enshrined little drawing over the years.

Recounted at the request of Walter Fordham for the Chronicles of CTR.

© 2009 William Gilkerson