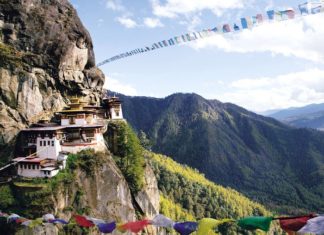

The bio/memoir of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche deserves at this point its own sub-category of Chögyam Trungpa Studies (hopefully soon to be a department at a major university). Diana Mukpo’s Dragon Thunder presents a kind of official remembrance by his wife, covering all the major events and well-gossiped anecdotes of his tenure in the West. Warrior-King of Shambhala by Jeremy Hayward explores much more of the institutional development of Trungpa Rinpoche’s work. Fabrice Midal’s, Chögyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision, while keeping up a thread of biographic chronology, makes an encompassing summary of his many areas of teaching. For his early life of youthful monastic training in Tibet and escape from the Chinese over the Himalayas, we have his own autobiography, Born in Tibet. To these others we should add Johanna Demetrakas’s excellent film documentary, Crazy Wisdom, and of course The Chronicles of Chögyam Trungpa website.

The bio/memoir of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche deserves at this point its own sub-category of Chögyam Trungpa Studies (hopefully soon to be a department at a major university). Diana Mukpo’s Dragon Thunder presents a kind of official remembrance by his wife, covering all the major events and well-gossiped anecdotes of his tenure in the West. Warrior-King of Shambhala by Jeremy Hayward explores much more of the institutional development of Trungpa Rinpoche’s work. Fabrice Midal’s, Chögyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision, while keeping up a thread of biographic chronology, makes an encompassing summary of his many areas of teaching. For his early life of youthful monastic training in Tibet and escape from the Chinese over the Himalayas, we have his own autobiography, Born in Tibet. To these others we should add Johanna Demetrakas’s excellent film documentary, Crazy Wisdom, and of course The Chronicles of Chögyam Trungpa website.

To those used to biographies of more ordinary, albeit famous and/or important people, Trungpa Rinpoche manifests the kind of spiritual figure for whom any account compels interest, where even very seemingly small interactions can have a potent effect on the person involved, and then when related to others becomes a teaching, a bright flash of dharma every time. His name, an amalgamation of Chökyi Gyatso, meaning “Ocean of Dharma,” and thus, however many accounts we hear of his interactions, there’s always some further illumination. As Mr. Berliner notes of his own new memoir, “This book presents the story of my life as only one reflection in the radiant mirror of his life. It is certainly not the story of his life in any complete way, since none of us who knew him could ever write about more than the few reflections each of us saw in entering his world.”

With both the previous memoirs coming from Brits, this is the first by an American with the characteristic experiences of a baby-boomer coming of age in the 60’s: college years (Yale); pot-smoking and acid-dropping; the psychic earthquake of the JFK assassination; English teaching in a ghetto school; a questioning of received wisdom at political, social, and philosophical levels; a quest for meaning and psychological health. Berliner adds an interesting wrinkle to the Trungpa memoir by making a clear thread of his relationship to his father appear throughout the story. His feisty, charitable, charismatic, and demanding father becomes both an inspiration to Berliner’s life choices and a place in himself he struggles to reconcile with.

In another characteristic move of the era, Berliner ignores his Yale education and goes back to the land, living as a farmhand and maple syrup entrepreneur in Vermont, successfully learning to work with his hands and overcome the existential malaise of his youth. Drawn to Naropa University in its famous inaugural year, 1974, he hears Trungpa Rinpoche teach and resolves to become a full-time student at age 29, moving to Karme-Chöling, only sixty miles from where he’d been living. The welcome he receives upon arrival would cause a great deal of consternation if it came to the attention of a Shambhala executive committee today: “Seeing a few men my age sitting on the front porch in the warm Indian summer evening, I smile in greeting. They douse my smile with expressionless gazes. No one stands up to greet me. No one offers to help me unpack or even to point me in the direction of an officially welcoming face.”

That, Berliner comes to surmise, results from Trungpa Rinpoche’s particular emphasis in those days on facing your mind and life alone, without hope of exterior salvation. Perhaps fortunate to have worked through some of this dourness already and not dissuaded by the underdeveloped Karme-Chöling hospitality department, he enters full-on the life of a practice center with his career as a Buddhist now fully engaged.

This, of course, means practicing sitting meditation. Reading his account, I can’t help but think of my own early struggle with it—the relentless physical pains and the “Rube Goldberg contraption” of cushions employed trying to ease them. How everyone else looks to be sitting so calmly. How his “mindfulness of…breathing bobs up and down like a tiny lifeboat in an ocean of emotional turmoil.” He manages two dathuns (one month sitting retreats) in four months, studying the hell out of the available seminary transcripts, then presents himself as an appropriate candidate for vajrayana seminary and transmission to Trungpa Rinpoche.

It’s in these scenes, dialogues with Rinpoche apparently burned into Mr. Berliner’s memory, still vivid after 35 years, we can see how Rinpoche got so much out of even seemingly simple interactions. The precision and nuance of the descriptions bring out the indelible flavor of relating with Chögyam Trungpa:

I sit in front of him, frozen in my silence. He does absolutely nothing to help me with my discomfort. His own silence merely heightens it. He takes a drag on his cigarette and places it on the lip of a black plastic ashtray. He looks at me for a long time without saying a word. His dark brown eyes are unutterably gentle and deep. I cannot hold his gaze as if I will fall into those eyes and never find a way back out. He seems to wait for me, but without waitingas if we had all the time in the world.

I try to remember why I’m here and what I came for.

“What’s up?” he says at last, taking another drag on that cigarette. It feels like he’s been smoking it for hours.

“I have a request,” I manage to squeeze out at last.

“Sure,” he responds in a way that is both intimate and noncommittal.

“I’d like to go to the next seminary.”

He takes another sensual drag on that cigarette. The space seems to become solid. The smoke, my words, his slow and deliberate gestures, all encased in a kind of psychological amber. My body, on the other hand, begins to feel slightly hollow.

“What’s the rush?” He lets the slightest trace of a smile waft my direction.

A remarkable amount of power comes from such a simple thing as sitting with Trungpa and watching him smoke. Need we mention here that smoking was one of his most infamous religious transgressions, though in clear retrospect he was taking on a now faded cultural modality, one we’re amply reminded of by Don Draper and his world in Mad Men. A variety of seemingly opposed elements find themselves in delicate, telling balance: the student’s aspiration and ambition, the teacher’s unyielding silence with eyes “unutterably gentle and deep.” But that gentle depth also holds the possibility of falling down the cosmic rabbit hole. By the time we get to “What’s up?”, time has turned to taffy. The student can barely talk. The teacher says one ordinary word, which manages to be the unlikely combination of “intimate and noncommittal.” By the time the student makes his request, his whole perception of reality has begun to shift, and perhaps even more subtly and more slippery, his premature request is already meeting with a now hard to negotiate moment, like the weather had already shifted and made the decision on its own. The teacher’s smile starts lifting the request and carrying it away.

As Berliner goes from back-to-the-land hippie to international model and head of Shambhala Training, he also goes through more of these interactions, where the awake nature of reality pokes through and his ego receives excruciating and concise surgery. He brings his parents into contact with Trungpa Rinpoche and his world, though not always understanding it, at times they’re definitely charmed. The 16th Karmapa assures them in an interview that to have raised a dharma practitioner like their son is very meritorious. His father still struggles over what he’s done with that expensive Yale education, and he must contend with his father’s scientific atheism and antipathy to organized religion, reversing the stereotypical nodes of western spiritual rebellion.

All memoirs of Chögyam Trungpa lead inevitably through his death at the wrenchingly youthful age of 47. On the last occasion of seeing him alive in California, Trungpa, having spent the last years of his life promoting the principles of his Shambhala teachings and enlightened society as a cure for the materialism of the modern era, prophesies the coming era in America. Berliner, paraphrasing Rinpoche from memory, describes him saying:

This country will become unrecognizable to you in the next twenty-five years. There will be crises and challenges of all kinds—the economy, the climate, politics, the spiritual scene. There will be huge ups and downs financially and in terms of livelihood. There will be extremes of climate—fires, floods, earthquakes, unlike anything in the past.

There will be much more fear, which politicians will take advantage of. There will be much less hospitality for spiritual views and practices that are seen to be outside the mainstream. There will be a rise of religious fundamentalism as if you’re living in a third-world country.

There was much Chögyam Trungpa did that defied conventional norms or that seemed hard to fathom, from micro interactions with students to a prophetic preparation for coming darkness in America and around the globe, but live or dead he remains like a firey torch. A quality that Mr. Berliner especially brings out in his account is how Chögyam Trungpa continues to resonate in the lives of his students, in their meditation practice, in conveying his teachings to others, in what career one pursues (in Berliner’s case, becoming a therapist), in the needs and demands of personal relationships, in turns in life and in car accidents. The same prickly, heart-opening qualities manifest in relating with the guru are apparent as he relates with his father in the process of aging and death.

In graceful, quick-reading prose, Mr. Berliner adds some welcome, further gleams of light coming off the transmission and legacy of Chögyam Trungpa, demonstrating how the guru continues to bring the student face to face with the reality of his own heart.

Gary Allen is the Education Director of the Ratna Peace Initiative, a non-profit which teaches meditation to inmates and military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. He has two degrees in Writing and Poetics from Naropa University. He’s the author of two books of poetry, most recently Love Strolls Among Its Own Fires (Turquoise Dragon Press). He’s currently working on an extensive biography of the Indian mahasiddha, Tilopa, and lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Gary Allen is the Education Director of the Ratna Peace Initiative, a non-profit which teaches meditation to inmates and military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. He has two degrees in Writing and Poetics from Naropa University. He’s the author of two books of poetry, most recently Love Strolls Among Its Own Fires (Turquoise Dragon Press). He’s currently working on an extensive biography of the Indian mahasiddha, Tilopa, and lives in Boulder, Colorado.