Last month (May 2018), while I was in Boulder to spend time with my family there, I visited with my old friend, Kunga Dawa (Richard Arthure). I had called ahead from my home in New York, and he had told me that he would love to see me, if he was still alive, as he had already had two heart attacks. He sounded so cheerful and vital, I found it hard to imagine that he would die soon.

We spent the better part of an afternoon, laughing and reminiscing, sharing our mutual devotion to our root teacher and the teachings. He told me again that he expected to die in the near future, and again I found it hard to credit, he seemed so full of happiness, intelligence and humor… life! I believed him with my mind, if not with my heart. I have known Kunga for 48 years now.

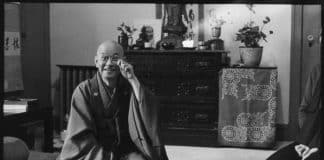

In February or so of 1970 I went to hear a Tibetan lama speak in mid-town Manhattan: Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. I had met Ram Dass a couple of years earlier, had set off on my own spiritual quest – Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, Christianity, Sufism, and a bit more – and now I was going to listen to a Tibetan Buddhist teacher. I went with my friend and fellow traveler, Charlie Rokoszak, now passed these many years. We sat in the back of a well-lit room on folding chairs.

At the time I didn’t know that Rinpoche had recently come to this continent from England and Scotland, nor did I know that he had landed in Canada and was stuck in Toronto, waiting for a US visa. So I was surprised when a Caucasian fellow walked through the door – handsome, with curly light brown hair, blue eyes, he seemed to look directly at me across the tops of the heads of the seated audience and flash me a brilliant smile. Of course, it was Kunga.

While I have never forgotten the smile, I no longer remember what he said, but it was enough so that a few months later, when Rinpoche actually did come to New York, I went again. This time the talk took place in a darkened loft somewhere in the southern part of the city. I was seated on the floor, trying my best to maintain full lotus (to impress the teacher?). Rinpoche came in wearing a business suit and tie, accompanied by a blond girl in a mini-skirt, Diana of course. Rinpoche gave a talk on the importance of having a sense of humor. I did not find it funny and left, crossing him off my list of potential teachers.

That summer I purchased a ticket for a charter flight to India. I figured I would go and see if I could find a guru, as Ram Dass had done, or at least have a good adventure and smoke a lot of bang. I had sold the keys to my rent-controlled apartment and all my possessions, and I was camping in my cousins’ Park Avenue apartment while they were in Italy, waiting for my flight in August. It was late June and very hot.

Charlie, more impressed with Trungpa Rinpoche than I, had gone up to Tail of the Tiger (now Karme Chöling) in Vermont to hear him teach. We spoke on the phone, and he suggested I beat the New York heat and join him, hear some dharma (I knew almost nothing about Buddhism, in spite of a course in college), and we would have a good time. I took my Abercrombie and Fitch sleeping bag (they sold sporting equipment in those days), and clothes and caught a bus.

Tail of the Tiger was an old, Vermont woodcutter’s property: about 400 acres then with a ramshackle house, a large, ancient barn, and a falling-down syrup shed. There were already about 30 or 40 people there, living in the house and camped on the grounds, including a few students who had accompanied Rinpoche from England: Kunga (Richard Arthure) was obviously Rinpoche’s closest student, and there were also Fran Lewis and Tania Leontov, who were very close to him and who ran Tail.

The rest of the crew I encountered included “the Brandeis Boys” (Alan Schwartz, Karl Springer, Chuck Lief, and Marty Janowitz), Michael Chender, Michael Kohn, Polly Monner (Flint/Wellenbach), George Samuels, David Wilde, V. Manoukian, William Hanniman (he was eventually the inspiration for the Vajra Guards), Fern, Olive Colón, Jack Niland and Sara Kapp, and a hitchhiker they had picked up on their way named Melanie, and more. A number of these are now dead.

Within a few days of my arrival I had formed a bond with Rinpoche which has endured and dominated the rest of my life. I think many of those present at that time experienced the same. Kunga, being the heart son, was much respected and held in some awe. One day I walked into the “library,” a small room with bookshelves and a few meditation cushions. There I found Kunga, alone, meditating. “Oh, I’m sorry for interrupting you,” I said, as I stepped through the door and saw him sitting on the floor. He looked up at me with that flashing smile and said, “Interrupted me from what?” I have never forgotten.

Later I encountered Kunga repeatedly, and we became friends. He continued to teach, and in 1971 Rinpoche told me to start teaching as well. But Kunga was the star. Until one day when he had been in San Francisco teaching, we received word that he had had a mental breakdown of some sort. The report was that he had tried to have sex inappropriately with a woman, had somehow gotten himself stabbed in the leg by someone unnamed, had been running down streets naked, and more. Rinpoche sent some students to San Francisco to bring him back, which they did. At that time Marvin Casper and I were living with Rinpoche in a house just outside Boulder, Colorado in Four-Mile Canyon. It was to this house that Kunga was transported, and for a few weeks I watched and participated as Rinpoche worked with Kunga. Eventually, he was committed for a few weeks to Boulder Psychiatric Institute. After that he calmed down and, more or less, recovered, but never again did he hold the position of prominence he had prior to his “break.”

That summer Rinpoche gave a seminar on the Bardos in a large camp on the Peak-to-Peak Highway outside Allenspark, Colorado. Many of us were camped out in tents; the lectures took place in a large space with a roof, dirt floor, and no walls. Altitude: about 12,000 feet.

One night we were sitting around a campfire with Rinpoche. The whole business with Kunga was unfolding in Boulder, and everyone at the seminar knew about it. The question in everyone’s mind: How could this happen to Rinpoche’s closest student? If it could happen to Kunga, what about me?

Rinpoche knew what we all were thinking, and finally he addressed the issue directly. Laughing, he said: “Everyone overestimates the importance of a guru. I’m just a clark (clerk) sitting in the booth. You buy the tickets, get on the train, and take the trip!”

Eventually Kunga was released from BPI and began living a more normal life. He held a number of jobs — I remember him selling cars at a local Boulder dealership — but I lost touch with him until some time in the late 1980’s or early 1990’s when he decided to go into 3-year retreat in New Mexico. At that time, one of his sons, Adam Arthure was living in the Boulder and Kunga asked me to visit him from time to time, as he would be in retreat and unavailable. This I did until Adam relocated and I lost touch.

After Trungpa Rinpoche’s death, Kunga studied with Tulku Urgyen and other lamas. Tulku Urgyen told him to spend as much time in retreat as he could, and so he did go into retreat for three years in a cabin remote in the New Mexico chaparral. There he wrote a number of the poems included in his book The Medium of the Breath. His poem, Remembering the kind root guru Chokyi Gyatso, the 11th Trungpa Tulku, is a product of that time. You may buy the entire book online at Xlibris.com (Kunga self-published it), and it is beautiful.

During this time Kunga also taught in various places in the U.S., including a few years ago at the Westchester Buddhist Center, which I and Derek and Jane Kolleeny run in Irvington. There he taught a seminar on … of course, the Sadhana of Mahamudra.

Kunga’s devotion to the dharma and his teachers was profound. Throughout his entire life his devotion never flagged, that I know of. I think it accurate to say that the dharma was his life. He is an inspiration to me and to many others. I and we love him, and I thank him for the example he has set. I remember him with tears of love and gratitude.

Ki Ki So So, Richard, Kunga Dawa. I love you and hope to meet you again. John