This meandering recollection was written over the days following Robin’s rather sudden, rapid decline and death, while I was traveling with a group of Western pilgrims in Eastern Tibet. We learned of his passing after returning from our time with Karma Senge Rinpoche at Kyere Monastery and Wenchen Nunnery, just before meeting the twelfth Trungpa tülku. We presented offerings so that all the Surmang monasteries and several other important institutions would engage in the appropriate ceremonies on behalf of Robin, during his journey through the bardo.

This account is lengthy, to be sure: way too long, no doubt; but it is offered with the aspiration that some of Robin’s friends and relatives might be interested to know something about his early days as a disciple of the eleventh Trungpa, the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. There are likely some inaccuracies and much missing history, so if others are inspired to amend this, you are most welcome.

Robin had many “best” friends, or so it seemed—both over time and in different situations. I was one of them, as he was to me, from fairly early on in our relationship. We joked that we had probably been married in one or more previous lifetimes. The ease and depth with which we shared our journey as fellow students of the Vidyadhara, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, seemed important and helpful to us both.

My first memory of Robin was of him giving a talk at Tail of the Tiger (now Karme Chöling), circa 1972. I was visiting there during a break from college; Robin was living there. Only years later did I learn how pivotal this particular evening was for his ability to remain there. Residents took turns giving a weekly “house talk” during the nonprogram times, and this evening was Robin’s first such occasion. While these were supposed to be dharmic in content, they were often an opportunity for the speaker to complain about aspects of life at Tail. Just as Robin was beginning his talk, Rinpoche quietly slipped into the back of the room to observe. He left just as quickly and unobtrusively as soon as the talk was over, not staying for the question period.

Robin’s talk was about nagging people, or more likely being nagged by others. He presented this in a somewhat madhyamaka-like analysis of the nagger, the naggee, and the “nag,” the act of nagging. It was characteristically humorous, engaging, and clever. Rinpoche must have liked it, since I think it was on that basis that the executive committee soon after decided that Robin could remain at Tail. There apparently had been some real question about whether that was a good idea up to that point.

I didn’t get to know Robin on that visit, but I remember him wandering around the house (It was just a large old farmhouse then), always reading a book, with another book under the other arm, and at least a couple more stuffed in his pockets.

I’m not sure exactly when our friendship began—probably during a seminar at Tail later that year or next. But we were deep into it by the summer of 1974, when Robin came out to Boulder for the first summer of Naropa Institute, where I worked as an administrator. Having attended the first Seminary in the fall of 1973, being in Boulder afforded Robin the opportunity to join the still-very-secret second “tantra group.” Robin and I spent much time together then, including our first really disciplined effort at learning Tibetan, by taking an introductory course taught by Jan Nattier, now an accomplished Buddhist scholar. We already knew some of the basics of the language, but that had been largely self-taught. Robin had previously studied French, Russian, and Chinese, and he had attained some level of proficiency, especially with the first two. I had studied Sanskrit, Pali, and a bit of Russian, Spanish, and Hebrew. We shared a passion for such pursuits—especially as they applied to the dharma, which was always the main point for us. In the early 1970s, Robin had done an English translation of the Life of Marpa from J. Bacot’s French translation.

Rinpoche asked Robin to be his cook and housekeeper during the 1974 Seminary, which took place in the fall at Snowmass Resort, Colorado, a resort in the moutains near Aspen. This was my first Seminary. Due to our friendship (and, of course, Rinpoche’s kindness), Robin invited me over often to Rinpoche’s house, about a mile away from the hotel where the Seminary took place. “Can Larry come over to play—” Robin would inquire with Rinpoche, and I seemed to become an adjunct member of the household at times, which was an incredible treat and opportunity to be with our guru.

Robin and Rinpoche had a wonderful relationship, it seemed—very jovial, intellectually stimulating, and very warm. Rinpoche appeared naturally to fill the vacuum of a surrogate father for Robin, who had lost his own to lung cancer before I met him. I remember accompanying them on a shopping expedition to Aspen one day, when Robin delighted Rinpoche by finding a cookbook entitled something like Innards and Other Variety Meats, and together they began experimenting with many of the recipes for tripe, brains, Rocky Mountain oysters (sheep balls), and the like—often not telling the dinner guests what they were eating until it was too late!

Robin taught Rinpoche various Chinese characters, which I don’t believe Rinpoche knew much about before then, and Rinpoche taught Robin the Tibetan handwriting script, which he learned quite well—the first among us to attempt this. Rinpoche practiced the Chinese stroke order diligently, delighting in adding more richness to his calligraphic palate.

__________________________________________________________________

As Rinpoche once proclaimed a couple years later at the first Dharmadhatu conference: “I have attained the bhumi of patience . . . due to the kindness of my students.”

__________________________________________________________________

As anyone who knew Robin will appreciate, there was the occasional indulgence. Robin became addicted to a recent Joni Mitchell album, which he played continuously for weeks, it seemed. Curiously Rinpoche seemed just to endure it, occasionally making a face or rolling his head to the music. (As Rinpoche once proclaimed a couple years later at the first Dharmadhatu conference: “I have attained the bhumi of patience . . . due to the kindness of my students.” There is no doubt about that, as surely his students can attest.)

After the second summer program of Naropa Institute in 1975, Rinpoche told me about a dream he had. He mentioned the dream just as he entered the “old townhouse” up on the hill in Boulder in order to perform the wedding of Wendy Nelson and Gary Webb. He said that we had to talk about something important. Of course I spent the whole wedding worrying about what this was, and finally was able to have a moment with him during the reception. He said that his dream indicated that after teaching at the Seminary that fall I should move to Karme Chöling (KCL; renamed from Tail of the Tiger by His Holiness Karmapa XVI the previous year on his first visit to the West). I actually had asked to move there sometime earlier, but Rinpoche didn’t seem to think this a good idea at that point. I was very happy about the prospect of moving there, and the plan was for me to work with Robin, who was in charge of the educational program. I would join the teaching staff, though that sounds more exalted than it seemed. I was to remain there for at least several years.

I’m not sure whether Robin had created the “Eight-Week Program” at Karme Chöling; but he was clearly a major promoter and teacher of this innovative model: two weeks of intensive hinayana study, along with the daily schedule of about four hours of meditation practice and a similar-length work period; a full dathün (one month meditation intensive, about 8-10 hours of practice/day); followed by two weeks of intensive mahayana study. It was an excellent format, and we conducted these at least twice a year, I think.

Robin may also have designed the Buddhist ministerial program there for veterans. This was an ingenious program, funded by the US government via its benefits for veterans, which provided just the right amount of capital to allow for a person to live at KCL and participate in the “three wheels” of Buddhist meditation practice, dharma study, and everyday work activities. The veterans were monitored regularly, reports filed with the proper agencies, and eventually (I believe upon completion of Seminary—then a three-month residential program with the Vidyadhara), they would become Buddhist ministers. I suspect only a couple people went through the entire program, but a number of people received these veterans’ benefits, as did KCL, of course.

Robin’s mother Elsie came to visit once. She came to KCL from her home in Nashville, Robin’s birthplace (though he grew up in New Orleans). A petite, white-haired southern lady, she bore little resemblance to Robin except in her gracious southern ways. She smoked Vantage cigarettes (as did I in those days, so she would never allow me to use my own), and she carried the essential ingredients for a dry Martini in her purse. Upon her arrival, Robin sat her down on a chair in his room (what is now the back half of the upstairs suite), and he paraded each and every member of the staff through in a very orderly fashion. Elsie was treated like visiting royalty. She engaged each person in conversation for a few minutes, moving through the entire population of KCL over the course of a couple hours. After the last person exited, she said to Robin and me, “Now Robin, let me tell you who clicks with this place and who does not.” With not a single exception, her vajralike perception accurately nailed each person, who she remembered by name in nearly every case. She was remarkable, and highly entertaining, revealing a most amazing influence to all of Robin’s friends there.

During my time at KCL, H.H. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche came to the States for the first time, in 1976, at the invitation of the Vidyadhara (VCTR). Robin and I, knowing a little Tibetan, were keen to attend to His Holiness’s needs, spending as much time as we could in his presence. He was ensconced in what is now the Vajrayogini shrine room on the main floor, opposite the library. We watched him meditate upon arising in the early morning; he spent the rest of the day always reading (and seemingly practicing) an endless number of Tibetan texts amidst whatever other activities presented themselves: interviews, meetings, meals, and correcting his grandson Rabjam Rinpoche, then a young boy, who was engaged in “reading” practice, which consisted of spelling out loud the Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa during much of the day. Amazingly, HH corrected him merely from his memory of the text.

I remember observing that HH not only used a mala in his practice, but he was also using the counters—obviously keeping track of the number of his recitations. This depressed me terribly, as it seemed that if an accomplished master like HH was “still counting,” then surely there was no hope whatsoever for many of us! Fortunately, I was able to mention this to VCTR some weeks later, to which he replied, “Oh yes, I asked HH to do a million recitations of the Ekajati mantra in order to further empower the place.” I was so relieved to learn that HH had simply been on the job, with a project like that to accomplish.

Robin and I witnessed something during HH’s visit that made quite an impression on us both. One afternoon, Joel Wylie, a student of HH, not part of our community, had quite a testy conversation with him, only some of which could we understand. But there was no missing the fact that HH had been very sharp and critical with him. It was frightening to witness—no doubt more so for Joel—and it was the first time we had seen a visiting teacher be anything other than all smiles, so to speak. Of course we had experienced our own guru’s “black air” or other critical aspects—a raised eyebrow being sufficient to do permanent damage, or so it seemed. It was very instructive to see another teacher deal with his own close students, and it was sometime in marked contrast to how they manifested with us.

Some months later, the night before HH was to depart N. America, Lama Ugyen Shenpen, one of his two attendants (the other being Lama Yönten Gyatso, a long-time attendant of VCTR at Surmang, pictured in Born in Tibet) had a dream that perhaps it would be beneficial for him to remain in America with us. He discussed this with his guru, who in turn discussed this with VCTR, and Rinpoche agreed that we would take care of Ugyen and that he indeed could be very helpful. (In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine how VCTR would have been able to accomplish so many things in the realm of translation and cultural transmission without him.) KCL was really our only full-time care facility, so to speak, providing three meals a day and a very supportive environment; and with Robin and me in residence, it was the natural place to assign Ugyen, who knew not a word of English. You might say it was the closest thing to a monastery in our world—a lay monastery.

I think Steve Mains, a lawyer living at KCL, began to work on Ugyen’s immigration as a Buddhist minister, with help from Pamela Gold (Bothwell) from NYC, and Robin and I set about to work on our Tibetan with him. Rinpoche suggested we work on the short Vajrayogini sadhana with him, the longer one already under preparation in Boulder. Others helped him to begin English lessons. A very warm and long-lasting friendship among the three of us was established that summer and early fall of 1976.

In preparing for his summer seminar entitled “Meditation and Prayer in the Buddhadharma,” Rinpoche asked Robin and me to do some research on Christian mysticism—we being two rather unqualified Jews. We went over to Rev. Blankenship’s home (a Barnet minister nearby), who kindly lent us a couple of armfuls of books, and we sat with Rinpoche perusing them in the afternoons before his talks.

I remember very little from those sessions, except for one quite amazing discussion in which codirector Bill McKeever was in attendance. Bill sat opposite Rinpoche; Robin and I were on either side of Rinpoche. The discussion was focused on a wide range of the paranormal. Robin would tell a story about his time in India with Muktananda, where he was some kind of temple guardian. Then Rinpoche would tell us a story that was more unusual or strange from his experience. I recounted times from my high schools days, studying with a Spiritualist minister in Patterson, NJ, and Rinpoche would do better yet again. Back and forth it went—all seemingly designed to blow Bill’s Protestant-background mind, as he sat there increasingly incredulous.

I wish I could remember more of the stories, but let me mention just one for now. At some point, Rinpoche turned to Robin and said, in illustrating his point, “For instance, Robin here might become a lokapala of KCL after he dies,” noting the long-term relationship that he had with the center. Robin instantly got all puffed up and proud at the thought. He then said to Rinpoche something to the effect of, “When you die, would you become a lokapala to all the centers —”

“Heavens no, I hope not,” was the reply, instantly deflating Robin and intriguing us all. What ensued was a wonderful discourse on the differences between lokapalas, dharmapalas, gurus, yidams, and a host of other deities and the like. (Take a look at “Visual Dharma: The Buddhist Art of Tibet” in The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa, vol. 7, pp. 261-279 for a terrific overview of some of these topics.)

Somewhere around this time, Robin informed me about a conversation he had had with Rinpoche concerning our relationship. We both knew it was somehow special and deep, as I’ve already mentioned. But Rinpoche told him that I was his kalyana-mitra, “spiritual friend,” and that he should listen to me. Naturally, I have some misgivings about whether I should mention this at all; but I do so now mostly to illustrate something about how the Vidyadhara worked so intimately with us all, and I hope this is in some way useful to our understanding. I think this occasionally helped me to go beyond my normal knee-jerk reactions, as if I had taken a special vow of some sort.

I was incredibly touched that Robin shared this with me, and I have always tried to be mindful of not abusing this in any way. In fact, I think it really had very little impact on how things went with us, as so many aspects of our relationship were quite effortless. We gave each other all sorts of advice and feedback from time to time, and there were no taboos I can think of.

Also that summer, Narayana (aka Thomas Rich) was empowered as the Vajra Regent at a formal ceremony in Boulder. Soon after, he came to KCL to teach his first seminar in that capacity, “Feast of Devotion”—coming home to his early sangha roots in Vermont. It was a marvelous occasion. Many of us could not help but wonder whether he was capable of assuming such a prominent role as dharma heir and spokesman for our lineage. But this was certainly a good start.

One evening during his visit, Hector MacLean, Robin, and I were invited over for dinner at Bhumipala (Sanskrit for the Tibetan “Sakyong”) Bhavan (BPB), VCTR’s residence on the other side of the property. It was a very elaborate, multicourse affair, served with some degree of elegance. While we were all good friends, there was definitely something odd about the three of us being invited that night, and toward the end of dessert, Hector braved the question of why we had been invited to such a sumptuous display. The Regent threw down his cloth napkin on the table and declared, “It’s time for three funerals,” and we adjourned to the living room for after-dinner drinks and further drama.

The Regent began with Hector, who sat furthest away, opposite him. “You’re going to Boulder to be the assistant director of Naropa Institute” (Karl Springer recently having been appointed the new director there, after Marty Janowitz’s tenure). Hector was a long-time resident of KCL, a very grounded and capable person, but not exactly academically oriented, so this was probably received with some trepidation, as such appointments often were. We were all quite nervous at this point, our senses not nearly dulled enough from the various intoxicants imbibed thus far.

The Regent turned to me next, sitting somewhat between Hector and Robin. Robin grew more tense and began fiddling with his tie in a peculiar fashion. The Regent said to me, “You already know where you’re going.” True, I had heard a few days earlier from Jane Moskowitz (Vosper) via my girlfriend, Gail Redeker (Flynn), that I was to be a codirector of RMDC (now Shambhala Mountain Center). But as I had been at KCL for barely a year, and going there seemed somewhat preposterous at that time, I had not taken this seriously at all.

“That’s right,” the Regent continued, “you’re going to RMDC as one of the directors.” Robin began to swallow his tie at this point, for he knew that he too would be going wherever I was. He could barely speak; the Regent laughed, nodded his head to him, and said, “Yeh, you too!” You have to understand that in those days, for many of us, perhaps especially for such intellectuals, not-very-handyman-types, this was the Vajradhatu equivalent of a Siberian outpost. Robin had lived at KCL longer than anyone previously—around five years, I think. It was a frightening prospect to leave the womb for the wild West.

__________________________________________________________________

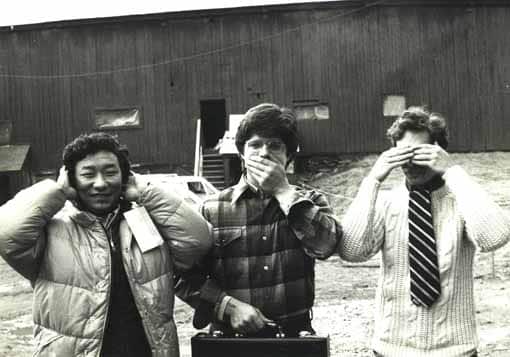

And so, a few weeks later, we set out for our own Journey to the West . . . a cross between the three stooges and the three musketeers.

__________________________________________________________________

We asked if we could take Lama Ugyen with us, which seemed somewhat likely, as there was the notion that RMDC was to become a translation center in part, though the Regent especially downplayed that aspect—a symptom of a serious lack of communication between VCTR and the Regent (another story entirely). And so, a few weeks later, we set out for our own Journey to the West, only vaguely reminiscent of the adventures of Monkey, we being a cross between the three stooges and the three musketeers.

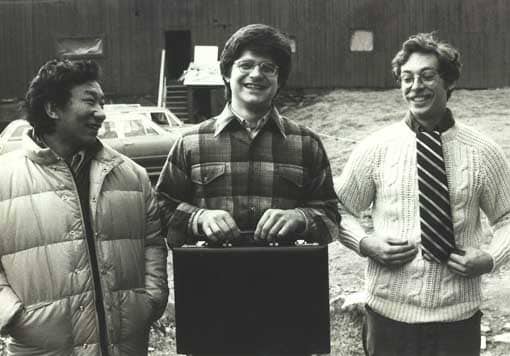

Lama Ugyen, Robin, and Larry set out for Colorado with farewell gifts from Karme Chöling:

a down jacket for Ugyen, a briefcase for Robin, a tie and sweater for Larry.

Karme Chöling, Autumn 1976.

We took my old Volvo (often the only car that would start in Vermont’s -40 degree weather, which was the temperature there for most of my first week in the winter of 1975), and we stopped for a few days to visit my folks in New Jersey, and to visit college friends in Ann Arbor. Robin and I took Ugyen to see “Gone with the Wind,” perhaps one of his first dramatic features. Ugyen seemed puzzled by a theater full of people in tears. We headed to Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin, where the 1976 Seminary was just getting underway, and where we were expected to present our translation of the short Vajrayogini sadhana.

The 1976 Seminary was a landmark event in many ways. During Seminary, the Vidyadhara discovered the root terma text of The Golden Sun of the Great East and received the transmission of the stroke of ashe, giving birth to the Shambhala teachings in tangible form. And he conducted the first vajra feast in America (as far as I know, for about 20-25 tantrikas at Seminary, around the beginning of the vajrayana section).

We arrived at the Seminary just after the first part of the terma had been translated by Rinpoche, working with David Rome, his secretary. As we emerged from my car in the parking lot of the King’s Gate Hotel, a tapping was heard at a window upstairs. There was Rinpoche beckoning us up to his suite. Excited, we hurried to find the room, at which point we were treated to a reading of the poem “Tung Shi” and its commentary, written perhaps a few days earlier, as well as the first section of the root text. Rinpoche demonstrated the stroke of Ashe, and we all looked at each other as if we had just landed in a new world, exciting yet very mysterious.

Lama Ugyen, Robin, and I had planned to remain at Seminary just long enough to review our translation with Rinpoche. After finishing this, we packed our bags and were ready to get in the car to depart for RMDC, but Rinpoche wouldn’t let us leave. He said that we were now going to translate the full sadhana and that Lodrö Dorje, Dana Dudley, and Chris Keyser were coming from Boulder for this. We had no idea of the bigger picture now emerging. As Rinpoche said, “How can you have a translation group if you don’t bring everybody together—” Robin and I said “A ha,” and settled into new quarters for most of the rest of Seminary.

After a week or more of sharing a corner suite in the hotel (Robin and I in one room, Ugyen in another, with a work room between us), Robin and I were moved out to a nearby rustic cabin, once inhabited by John Dillinger, we were told. There could be no more idyllic a situation in which to enjoy Seminary, each of us with our own bedroom, a shared kitchenette and bath. We worked very intensely all day everyday—first with Lama Ugyen, then with VCTR, going over the whole sadhana line by line.

The Regent was not pleased that we had not yet arrived at RMDC, but Rinpoche’s wishes of course prevailed. As VCTR was preparing to enter retreat for all of the next year, he wanted the Regent to begin to handle all administrative responsibilities, and so he deferred any conversations we wanted to have with him about our new posts to the Regent. We arrived at RMDC for Thanksgiving dinner. Richard and Alice Haspray were the outgoing directors, who remained for a month or so to help with the transition. Jacquie Bell, my codirector, pregnant with Wilson, arrived soon after the Seminary was over, and Tom Bell, who had already been living at RMDC, seemed well-established among the other capable builders, Paul Gauthier being the most experienced, along with Richard. Ugyen and I were taught how to roof the brand-new four-seater outhouse (still in use); I can’t remember what Robin did, but it was equally exciting, no doubt.

Robin and I moved into Gita, the largest house on the property at the time, which would remain his residence; I would move to Dhyana after the Hasprays went on to NYC, their next posting (Richard as NY’s first ambassador). Robin and I learned that we were indeed all too much like the odd couple, perhaps not quite so extreme, but it was not easy at all, either in the house or out. We had a staff of about 8 or 9 people at first, though that increased over the following year as the command to “build RMDC” came down in a big way. (We’ll leave that for another chapter.)

During a retreat I was doing in my house some months later, I noticed a fairly large furniture truck trying to negotiate the rickety wooden bridge nearby, clearly on its way to Gita. Sure enough, mama Kornman had sent Robin a household of furnishings—mostly things from the family home, more than enough so that some of us acquired a piece or two. She sent toilet paper and other amenities and, of course, a case of Googoo Clusters (a rather intense chocolate candy from Nashville), an item Robin’s friends looked forward to around Christmas time each year. Robin acquired a car at some point, and we often joked about making him a teeshirt emblazoned with “Drive the land,” as he went everywhere in his little car. We occasionally entertained ourselves with “Radio Mystery Theater,” one of the few surviving shows available to us.

Robin, Dana, and Ugyen departed after about a year, when it had become obvious that the translation center was simply not tenable at RMDC, which required an endless amount of other efforts to maintain the dharma programming, planning for much greater building projects, and the burgeoning community. I, too, returned to Boulder the following year, becoming the executive director of the Nalanda Translation Committee from that time forward.

Rinpoche’s first journey to Nova Scotia in May of 1977, in the midst of his year-long retreat, was largely funded by Robin, who had just become a Shambhala Lodge member. Having been involved in nearly all the translation activity concerning the Shambhala terma over the following years, these teachings became a central focus for Robin, especially after he returned to graduate school.

Robin, Dana, and Ugyen’s move to Boulder (in mid-1977 or so) precipitated the creation of a translation house (which also included John Rockwell and Scott Wellenbach). The translation committee rented a house from Bob (Mipham) and Abby Halpern on Juniper St., where Robin remained for a year or so.

Robin was quite fluent in French, and his love for Montreal resulted in a close working relationship with Les Traductions Nalanda from sometime soon after its inception in 1978. He visited there regularly, teaching some at the Dharmadhatu, and always working with the English-to-French translation process, being especially helpful with those texts that originated in Tibetan.

__________________________________________________________________

. . . he never tired of wanting to know more, test his ideas, and interact with his guru, who always seemed to delight in their banter.

__________________________________________________________________

Robin had an association with Naropa Institute for some years, teaching occasionally on Buddhism and meditation, as well as working in the publicity department. Robin worked closely with the Science Conference for a time, which brought together a very interesting collection of cognitive scientists and related disciplines. Sometime in the early 1980s, Robin studied Chinese (and perhaps other things too—) at the University of Colorado.

Robin was one of those students who always asked questions at Rinpoche’s talks. Though he was clearly more knowledgeable than most in attendance, he never tired of wanting to know more, test his ideas, and interact with his guru, who always seemed to delight in their banter. Yes, Robin loved the sound of his own voice, not unlike others of us (i.e., yours truly), but his spirit was usually warm, friendly, and inviting.

Robin was among a group of NTC members who first studied with Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche in 1985—first in Boulder, at the command of Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche, and then traveling to the Baca Grande in southern Colorado, where Khenpo Rinpoche taught a month-long course. He taught four sessions a day: two times in his bedroom to the NTC members, followed by talks to the whole group assembled, about a dozen people in all, believe it or not, having been invited there by Hannah Strong, who graciously hosted him on this first visit to America. Robin later went to Nepal to continue his studies of philosophical texts with Khenpo Rinpoche in 1987, I believe.

In search of both a career as well as an undying thirst for more intellectual challenge, Robin went back to graduate school at Princeton in the late 1980s, pursuing a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature. Suffice it to say, Robin was an insatiable reader in a number of fields, certainly not just Buddhism. His library is extremely vast—both rich and deep. Robin agonized over what his dissertation focus should be. Should he pick a topic that would help secure him a job, or should he explore his existing passions for Buddhist and Shambhala themes— We discussed this dilemma many times, and I’m sure he sought the advice of many others. In the end, he followed his passion, as Joseph Campbell popularized, choosing to study closely the epic tradition of King Gesar of Ling. (See Robin’s website at www.robinkornman.com for more on that.) He completed his course work and then traveled to France (1991) to work with students of the great Tibetologist Rolf Stein, one of the few Western academics to explore the Gesar literature in depth.

Already in his 40s, it was not an easy task to find academic employment. The field of comparative literature is quite large and diverse (just like Robin!), and Robin was probably a more unusual blend of talents and language fields than most. While I always thought that this ought to make him more interesting and attractive to schools, his significant talent as a teacher seemed to remain discounted—a story we’ve heard many times in academia.

He obtained a junior post at St. John’s College in Annapolis, MD, for two years, where he had to teach ancient Greek among other things, something he had never studied before, though he supposedly stayed successfully ahead of his class. The Socratic method there made little or no use of his lecturing abilities, and the combined eccentricities of both Robin and the institution itself never really jelled, it seemed.

Robin moved back to KCL for about a year or more in the summer of 1994, during which time he finished his dissertation, taught some as usual, and participated in the Khenpo program in the summers. He graduated with a Ph.D. from Princeton during this time (1995), and then accepted a three-year, nonrenewable position at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee (Bradley assistant professor of world literature, 1995-98) which became an enduring relationship over time, though never resulting in a full-time position after the initial term expired. During much of this time, Robin worked hard with Lama Chöying Namgyal (Chönam) and translator Sangye Khandro, translating three volumes of the Epic of Gesar. (See Sangye’s reminiscence about these days.)

Robin was a Luce Fellow (a title he quite enjoyed) at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., for an academic year (in 2001, “Nomadic Self-Knowledge in Inner Asia: The Tibetan Gesar of Ling Epic”), and they provided him with a wonderful office near the Asian Reading Room at this exalted treasury of literature.

Wherever Robin lived, he taught regularly and prolifically at the local Dharmadhatu or Shambhala center, usually developing quite a retinue of students, friends, and admirerers. There were rarely dull moments, as Robin relished an endless amount of company and interaction, and he brought together an amazing menagerie of diverse and friendly folk.

One of Robin’s closest friends was Susan Dexter, another NTC member and very experienced Shambhala teacher in Colorado. I think there were long periods when they talked on the phone daily, especially during the last years of Sue’s life. Robin suspected that she was very ill long before she knew this, and his fearlessness in sharing this with her was not easily accepted. I think Robin learned an enormous amount about the process of serious illness and death through his time with Sue, and he was able to be there with her at the end, outside of Boulder.

I, too, learned much from my regular talks with Robin during his lengthy illness. We discussed every aspect of it, and he was always remarkably candid and forthcoming in sharing his fears, his hopes, knowing all the time that no matter which extreme he might side with at any given moment, they were all just that—one more limited and confused, conventional reference point, not worth a damn bit of good in the long run. His knowledge of dharma always prevailed, much to his displeasure at times, as this is not conventionally comforting, especially as the stark reality of impermanence is staring you in the face—or in fact is your face. Robin was able to appreciate that, and his sense of humor was extremely useful and at times relaxing, provoking some kind of ease.

It was both remarkable and very touching that Robin, along with his good friend and doctor Jane Hawes, journeyed to Halifax to attend the Avalokiteshvara abhisheka offered by Karma Senge Rinpoche in mid-May of this year. Robin and Jane, a Tibetan-language student of Robin’s, were also able to attend several translation meetings with us during that time. Although he slept through a portion of the events due to his pain medication, Robin was incredibly moved and inspired to have received these ati teachings of our root guru.

He had been working with Wangdor Rinpoche especially, during his visits to Milwaukee, on understanding these pith instructions, and being able to make a very real and profound connection with the Vidyadhara’s ati termas was a culminating experience for him. He was ecstatic on the phone when I later described to him what we had learned from Karseng Rinpoche about practicing a ngöndro for Rinpoche’s terma teachings, and how he planned to transmit these over the next few years. He thought about nothing else for days, calling me back several times. Wangdor Rinpoche was extremely kind to Robin, and he clearly helped him quite a lot as the end was near, though none of us knew how near indeed.

Robin left many projects unfinished: notably his translation of the first three volumes of the Epic of Gesar, compiled in seven volumes by the students of Mipham Namgyal Gyatso. He embarked on an ambitious project to discourse on how Trungpa Rinpoche presented the Buddhist and Shambhala dharmas, especially during his time in N. America. I hope there will be some effort to collect whatever material there is from his many talks and essays (see Robert & Jill Walker’s Great Path Tapes & Books website below), and we very much hope that his translation and study of Gesar can eventually be completed. Quite a lot of work remains on this, from what I can gather.

I hope that this rambling reminiscence may inspire further efforts to document and share our mutual journeys together, in service of the profound and brilliant vajra teachings of both the buddhadharma and Shambhala traditions.

With deep gratitude and love for our dear friend, Robin-la,

-Larry Mermelstein