by Clarke Warren

by Clarke Warren

As we enter the year of the wood horse, it seems appropriate to delve into the qualities and significance of the horse in Tibetan culture. Students of the Vidyadhara, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and thousands who have read his book Shambhala, The Sacred Path of the Warrior have come to know of windhorse as a central theme in the Shambhala teachings. Windhorse is a dynamic fundamental principle of life and the cosmos, and the expression of basic goodness. It might be interesting to look at the cultural practices associated with windhorse in the Tibetan tradition, the wellspring of the Vidyadhara’s teachings on windhorse.

Let’s begin with a brief review of the Vidyadhara’s description of windhorse: “… it is the energy of basic goodness. This self-existing energy is called ‘wind horse’ in the Shambhala teachings. The ‘wind’ principle is that the energy of basic goodness is strong and exuberant and brilliant. It can actually radiate tremendous power in your life. But at the same time, basic goodness can be ridden, which is the principle of the horse. By following the disciplines of warriorship, particularly the discipline of letting go, you can harness the wind of goodness. In some sense the horse is never tamed—basic goodness never becomes your personal possession. But you can invoke and provoke the energy of basic goodness in your life…” -Chogyam Trungpa, Shambhala, The Sacred Path of the Warrior, pg. 84-85, Shambhala Publications.

Lungta is Tibetan for windhorse. It is a designation which carries a number of levels of significance, from the popular expression of folk religion to the deepest levels of spirituality, and it links the two. It holds a prominent place in Tibetan religious and folk culture, and has its equivalents in many other cultures.

Windhorse has its possible wellsprings in secular Asian cultures, and only later became associated with Buddhism. It is sometimes associated with the pre-Buddhist Bön spirituality of Tibet. Samten Karmay, in an excellent brief paper on the origins of windhorse, entitled Windhorse and the Well-being of Man*, traces its possible roots to China, on one hand, (where it may have been confounded with “river-horse”, another potent image and principle) and to India in another later, more Buddhist context. It has a presence also in both Chinese and Indian astrology. Whether windhorse is derived from either or both of these cultures, or more from native Central Asian horse culture roots, it was consummated in the Tibetan principle of the “ideal horse” (Ta-chok), which is always associated with the strength of wind. Certainly among horse cultures, the ideal of windhorse arose from the strength, energy, endurance, and dignity of the horse, and was a natural and omnipresent image to be drawn upon. As well, the sheer natural force of wind, which is both gentle and permeable in its unobstructed transparency yet strong in force, is a palpable natural image. Put together, the image of windhorse became a vivid and enduring icon.

The expression of windhorse as an image of spiritual and cultural significance is most visible in Tibetan culture as the omnipresent display of brightly colored and inscribed prayer flags in strategic places and sacred sites around the Tibetan world. It has its parallels in the colored prayer ties employed in Lakota ceremony. The custom of putting up prayer flags has also caught on in the modern West to a certain degree, where it is not uncommon in some places to see prayer flags hanging from trees or porches.

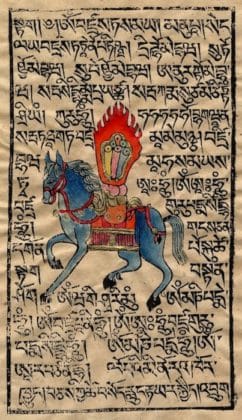

The popular explanation of lungta is that it refers to “good fortune” or “luck”. Surprisingly, a fair amount of the academic literature on Tibetan culture stops at this (with notable exceptions). But “luck” is a shallow sense of lungta. Windhorse refers to something much more basic and vital than mere “luck”, at least in the Western sense of the word. For instance, the prayer flags themselves are referred to as lungta, and are inscribed with drawings of the windhorse, accompanied in the cardinal directions by four other animals, each with its own symbolic significance (Tiger, Lion or Yak, Garuda, Dragon). Everything inscribed on the prayer flag, images, sacred mantras and prayers, is engaged to invoke and actualize the primal force represented by the image of windhorse, as well as ignite a visceral experience of it in one’s body and mind. In addition, such a force can set into motion influences that can shape events in society and nature.

The term windhorse also refers to the fact that the flags blow in the wind, or “ride” the wind, whereby the power of the sacred images and invocations printed on them are dispersed into the world at large, benefitting many levels of beings and the natural environment. The virtue accrued from the act of raising prayer flags then carries on into the life of the person(s) offering them, and to those whom they dedicate the merit of such an offering. This is possible because of the total interdependence of all mind, life and phenomena. Through such ritualistic gesture, joined with wholesome, magnanimous intention, that web of interdependence (Tibetan: tendril) can be accessed and influenced.

Lungta, on an even more primary level, refers to a fundamental bank of energy implicit in life and phenomena. The wind in windhorse also relates to the breath and its essential role in sustaining life, to the extent that to breathe is to be alive and vital. The horse refers to “riding” the energy of the vital breath, and hence of life itself. It could almost be equated with “life force”, though it infers a great deal more than mere biological energy. It shares similarities with the Chinese notion of “Chi”, to the Sanskrit yogic designation “Prana”, and to the Navajo theme of “Nilch’i”, or “Sacred Wind”. Lungta is the basic vitality and creative potency of life, of individuals, and of the total environment, indeed the universe.

With respect to humans, lungta carries with it qualities, such as would be evident in a person with natural dignity, integrity, high spirits, fortitude, exuberance, robust health, charisma, a fresh sense of humor, and so forth. A person’s lungta is “up” when one feels these qualities in concert, or observes them in another, as in “He has good lungta today!” Conversely, if one is beaten down or depressed, lackluster, and not connecting to the events of their own life and their environment well, then it is said their lungta is “down”. As a consequence, they are vulnerable to sickness, attack from others, misfortune, and so forth. A person’s lungta is a register of their relative synchronization with their own body and mind, and the world around them. So in this regard, lungta also has a protective function when successfully invoked.

Tibetan spirituality is replete with methods, rituals, and practices to “raise lungta”, or revive and stabilize windhorse. On the more immediate level, one can take one’s posture, breathe in fresh air, revive one’s sense of humanity, dignity and presence, and then project that out to their world in order to synchronize oneself with people and events in the world. Another way of arousing windhorse is to wear good decent clothes, although it is also said that if one’s lungta is strong, whatever one is wearing is splendid. In Tibetan culture, for instance, the new year, losar, is celebrated in one’s finest attire, and always with at least one new item of clothing. This kicks the year off by raising personal lungta.

More ritualistically, there are practices designed to arouse windhorse, both in the individuals participating, and in the environment around them. Such practices include, again, the putting up, or “raising” of windhorse prayer flags, especially at places in nature regarded as sacred and potent. Windhorse flags are also raised where there is potential danger, natural disaster, or mishap, such as where the land, for example, has been depleted by fire, where a tragic accident has occurred, or at the confluence of rivers, which is believed to be a locale of capricious, potentially destructive energy. The lungta flags in this case are to restore vitality, and protect from further mishap. A vertical windhorse banner, called a Dar-chok, mounted on a flagpole adorns the roof of nearly all Tibetan households, as a constant conduit of windhorse to the household. Divination is also sometimes requested from a lama to determine which type of lungta (there are many), or prayer flags, should be raised to address a particular situation, and where best they should be raised, sacred sites especially being of particular potency for raising lungta. People will also put up prayer flags at sacred sites of pilgrimage as an essential offering and supplication, and to connect with the power and blessings of the place.

The dar-chok, the vertical pole adorned with a lungta banner, is also said to join humans with their divine origins in the wide open sky and space, or perhaps the wide open space of human nature and awareness. Tibetan mythology recounts that early humans were born with a mu cord, a shaft of light extending from their head to their origins in the sky. At some point in time, due to acts violating this primal sanctity, this vital connection was severed, and the mu cord disappeared. But the raising of dar-chok reestablishes this connection, and thus invokes the treasury of windhorse implicit in it. The same connection was reignited in marriage ceremonies by the placing of colored threads on the shoulders of the couple, or placing a brightly colored arrow in the back of the blouse of the bride, extending up over her head. This same gesture was then rendered into the placing of white scarves over the shoulders of others, the omnipresent Tibetan manner of honorifically greeting someone.

There is a whole class of practices in Tibetan culture known as sang, which is the ritual offering of juniper smoke or sage from a fire, accompanied by a liturgical invocation. These practices have an intimate connection with windhorse. The sweet, pleasing smell of the smoke billows up to the heavens, which is the abode of various divinities (Tibetan lha) who are embodiments of abundant atmospheric lungta, and from whom lungta is invited down onto the earth and its recipient inhabitants. For instance, Tibetan villages, towns, and communities are in proximity to an associated local sacred mountain or hill, from the upper reaches of which a sizable sang smoke offering is made annually during New Year celebrations. At the conclusion of the liturgical invocation, everyone present will let go with a shout at the top of their lungs, in unison, “Ki Ki So So, Lha Gyal Lo”, or “May the gods be victorious!” This very voicing of this “warrior cry” is also a way of rousing windhorse.

Most Tibetan households have a sang bum or smoke offering pot on the roof of the house, often in front of or near the Dar-chok vertical prayer banner. Sang is offered daily, in the early morning, to make offerings to the lha (deities) and invoke windhorse into the household. On the inner household level, a small, portable sang bum is used to burn juniper on coals, creating the invocational smoke. The pot is then taken around the house to both purify the various rooms of disruptive influence and magnetize propitious circumstances. Individuals, at that time, use their hands to waft smoke over their bodies, for the sake of clearing personal obstacles and inviting windhorse into one’s body and mind.

On the yet deeper planes of meaning, lungta is a basic spiritual principle or force inherent in the nature of the world and each individual. As Chogyam Trungpa said, “You should appreciate yourself, respect yourself, and let go of doubt and embarrassment so that you can proclaim goodness and basic sanity for the benefit of others. The self-existing energy that comes from letting go is called windhorse. Wind is the energy of basic goodness, strong, exuberant and brilliant. At the same time, basic goodness can be ridden, or employed in your life, which is the principle of the horse. When you contact to the energy of windhorse, you can naturally let go of worrying about your own state of mind and you can begin to think of others. If you are unable to let go of your selfishness, you might freeze windhorse into ice.”

In another place, Trungpa Rinpoche says, “The result of letting go is that you discover a bank of self-existing energy that is always available to youbeyond any circumstance. It actually comes from nowhere, but is always there. It is the energy of basic goodness.”

The notion of “goodness” here is that the fundamental nature of the world and its inhabitants, and the entire scope of phenomena, is without conflict and replete with nurturing qualities. It is characterized in various contexts as “basic intelligence”, “awakened nature”, “the fundamental inseparability of wisdom and compassion”, “the natural state”, and in many other ways, all meant to indicate this only seemingly elusive yet perpetually present and available bottom line of life and being.

It may seem ironic that windhorse as a spiritual principle was rendered, at least in part, from Asian warrior cultures, as vicious as some of them have been historically. The martial attire of the windhorse deities, such as Ling Gesar and the dralas (environmental warrior gods, or deities) of mountains and place, would indicate this association. Yet aggression and violence is the distortion and misuse of the basic energy of windhorse. In seeming contrast, windhorse assumes a balance of openness and gentleness with non-violent courage and fearlessness. Yet it is characteristic of such an approach to spirituality such as Buddhist Tantra and of the pre-Buddhist Bön spirituality of Tibet to harness the harsh yet efficacious tendencies of the world, and transform them into more magnanimous pursuits and values, using their own symbolism in the process. Thus Kublai Khan was “tamed” by the illustrious Tibetan Buddhist masters Karmapa Karma Pakshi and Sakya Pandita, and turned his prowess (windhorse) toward supporting the growth and practice of buddhadharma and Buddhist culture. Earlier, in India, the third century C.E. Buddhist Emperor Ashoka began his career as a ruthless military monarch carrying out a Machiavellian conquest of most of the Indian subcontinent. After a sudden piercing recognition of the sheer horror and destruction he had caused, he turned his mind and life about face, and dedicated the rest of his years to nurturing, promoting, and spreading Buddhist principles, philosophies, practice, and social models. In doing so, he employed the very military terminology and imagery that he wielded as a tyrant, but turned it around to express the exuberant forces of Buddhist spirituality. Such a term as “himsa”, or “violent force”, was turned to “ahimsa”, or “Non-Violence Force”, and vijaya, or “victory”, was converted to dharma vijaya, “Victory of Dharma”. (Dharma refers to both the buddhist path and doctrine as well as the truth it engenders). One could say, consequently, that windhorse is a formidable force all the more potent and efficacious because it is free of aggression and resistance. Conversely, windhorse is born from and adorned with the qualities of wisdom, compassion, and benevolent power.

In this regard, “basic goodness” does not refer to some naive “goody goody” belief that all things are all well and good despite the difficulty, pain and abject horror so persistent in the world, if only one can seal oneself away from those realities. Nor is it a hollow promise that in the end everything will be okay. Nor is it a branded commodity on the religious roster of belief systems. (Though it could be and has been appropriated by any and all of those tendencies.) Rather, it refers to a fundamental strength and integrity that has the power to work with both positive and negative situations without being unrealistically bound by either. It is “good” precisely because it is not caught in the aggression of good versus bad. Thus it transcends selfishness, territoriality, self-righteousness, arrogance, and other more limiting human characteristics, the very opposites of windhorse. The “basic” aspect is that once those very limiting human characteristics are let go, then basic goodness, having been basic to one’s life and situation all along, shines forth with all its qualities and strengths, such as windhorse.

From good windhorse, then, come many other boons and qualities of value to human existence and the environment: good health, prosperity, powerful personal presence, successful crops, absence of hail and pestilence, just leaders, harmonious relations in society, good business and so on. But equally, windhorse evokes the bravery, strength, and fortitude to deal well with bad health, scarcity, downturns in circumstance, corruption, calamity, drought, pestilence, hail, invasions, and so forth. The bottom line, though, is that for windhorse to be harnessed, the intention must be that it is for the benefit of all beings, not just oneself or one’s immediate companions. Windhorse, like basic goodness, is not something solid (wind), so can never be captured, domesticated or privatized, but can always be harnessed and ridden (horse).

Happy Year of the Horse, and may windhorse adorn and carry your life and activities for the year!

*Karmay, Samten, The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals, and Beliefs in Tibet, Mandala Book Point, Kathmandu, 1998.

Clarke Warren is a senior student of and teacher for Vidyadhara Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and lived in Nepal and Sikkim in Tibetan communities for thirteen years, directing and teaching in the Naropa University Study Abroad Program in Buddhist Studies. He and his wife Pemba Dolma now reside in Erie, Colorado.

© Clarke Warren, 2014

In Praise of Windhorse

“The wind of heaven is that which blows between a horse’s ears.” ~Arabian Proverb

***

“Where in this wide world can man find nobility without pride,

Friendship without envy,

Or beauty without vanity

Here, where grace is served with muscle

And strength by gentleness confined

He serves without servility; he has fought without enmity.

There is nothing so powerful, nothing less violent.

There is nothing so quick, nothing more patient.” ~Ronald Duncan, “The Horse,” 1954

***

“Ah, steeds, steeds, what steeds! Has the whirlwind a home in your manes Is there a sensitive ear, alert as a flame, in your every fiber Hearing the familiar song from above, all in one accord you strain your bronze chests and, hooves barely touching the ground, turn into straight lines cleaving the air, and all inspired by God it rushes on!” ~Nikolai V. Gogol, “Dead Souls”

***

“His (Gesar’s) skillful chestnut steed

Outwardly manifests as a horse

Inwardly, he manifests as the mind of enlightenment,

He is the emanation of Hayagriva

He is elegant, with a rainbow swirling about,

He has the treasure of the gait of swift wind

and the strength of the wings of birds,

He possesses the glorious strength of a snow lion,

His vajra mane flowing right and left

Magnetizes the drala of white conch garuda,

The vulture down on the points of his ears

Magnetizes spies of luminous torches,

His forelegs of wheels of wind

Magnetize the drala of the lord of life,

The four hooves of the steed

Magnetize the drala of swift wind,

On the tip of each hair, lha (gods) reside.

If you do not protect me, your child, who will you protect

Accept this purification and warrior drink,

Increase your power of swiftness,

Miraculously lead me to the place I desire,

Accomplish my desires

Arouse the activity of wind horse,

O horse, pu pu so so ca ca, increase!”

From the “Warrior Song of Drala”, an invocation and offering to the Tibetan epic hero Ling Gesar: (“Drala”: a focal point of cosmic strength, sometimes translated as “warrior god”.)

***

***

“Somewhere in time’s own space

There must be some sweet pastured place

Where creeks sing on and tall trees grow

Some paradise where horses go,

For by the love that guides my pen

I know great horses live again.” ~Stanley Harrison

***

“Brahma was excessively sparing with earth, water, and fire … The reckless expenditure of air and ether in his composition was amazing. And, in consequence, he perpetually struggled to outreach the wind, to outrun space itself. Other animals ran only when they had a reason, but the Horse would run for no reason whatever, as if to run out of his own skin.” ~Rabindranath Tagore

***

“A thousand horse and none to ride! –

With flowing tail, and flying mane,

Wide nostrils never stretched by pain,

Mouths bloodless to the bit or rein,

And feet that iron never shod,

And flanks unscarred by spur or rod,

A thousand horse, the wild, the free,

Like waves that follow o’er the sea,

Came thickly thundering on, …” ~Lord Byron, XVII, Mazeppa, 1818

***

“A horse is worth more than riches.” ~Spanish Proverb

***

“If the world was truly a rational place, men would ride sidesaddle.” ~Rita Mae Brown

***

“Horse sense is the thing a horse has which keeps it from betting on people.” ~W.C. Fields

***

“This self-existing energy is called ‘wind horse’ in the Shambhala teachings. The ‘wind’ principle is that the energy of basic goodness is strong and exuberant and brilliant. It can actually radiate tremendous power in your life. But at the same time, basic goodness can be ridden, which is the principle of the ‘horse’. By following the disciplines of warriorship, particularly the discipline of letting go, you can harness the wind of goodness. In some sense the horse is never tamedbasic goodness never becomes your personal possession. But you can invoke and provoke the energy of basic goodness in your life…” ~Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shambhala, The Sacred Path of the Warrior.

***

“The days run away like wild horses over the hills” ~Charles Bukowski