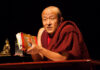

For those of us with a connection to Trungpa Rinpoche and his teachings, the significance of his escape from Tibet has been about the Dharma: because he survived, the Dharma he embodied has been planted in the West.

Grant MacLean’s new book, FROM LION’S JAWS, adds a fresh perspective. The story of Rinpoche and his traveling party’s escape is a story that ranks high among history’s very greatest accounts of courage and survival—a journey that is also a spiritual saga of the highest order, a shining example of leadership, and a source of personal inspiration for our own life journeys.

To illustrate the escape’s place in history, here is a brief overview comparing Trungpa Rinpoche’s 1959 escape from Tibet to Ernest Shackleton’s famous 1914-17 Antarctic Expedition.

Among the world’s most famous and often-told stories of human courage and resilience in the face of deadly danger and elemental challenges is Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17 —a journey recently celebrated as “history’s greatest story of survival and adventure.” Around ten movies and TV series have been produced on Shackleton and his expedition; about 18 books on the man, his adventure and his leadership are currently up on Amazon.

This is a quick guide to Chogyam Trungpa’s journey’s place in history, viewed in the light of the famous Antarctic expedition. It is an overview of key aspects of the two journeys, not a competitive comparison: every great story of human courage and fortitude in the face of deadly challenge is unique, each to be valued for itself—maybe more so when a leader puts his own life on the line for others.

There are, of course, many fundamental differences between the two journeys. But one crucial aspect of the Tibetan saga has no parallel in the Antarctic one along with the vast challenges of weather, terrain, navigation and food supplies, the 300 Tibetans were being hunted by the Communist People’s Liberation Army. This ruthless enemy dictated the refugees’ escape altogether, the routes they took and the very clothes they wore. If they were caught they would be interned, often subject to hard labour, the leaders almost certainly executed. The threat was all too real: the Communist assault at the Brahmaputra River greatly reduced the survivors’ numbers.

Both journeys unfolded in three pivotal stages: first, when their home bases were destroyed Shackleton’s ship Endurance by Antarctic ice, the Tibetans’ world by the Communists; the second involved exceptionally dangerous and challenging journeys across treacherous seas and unknown terrain; and the final, climactic stage played out in life-or-death crossings of high snow mountains.

Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition in contrast with Chogyam Trungpa’s Tibetan Escape

Leaders

Naval officer, experienced leader of Antarctic expeditions.

Buddhist lama; no prior relevant experience.

People

Crew: highly selected, seasoned men; fit and disciplined, many with military backgrounds.

Refugees: wholly self-selected group of monastics and ordinary people of all ages, from babies to the elderly, most with little relevant experience or sense of discipline.

1st Stage

5½ months: adrift on ice, then hard journey, voyage to Elephant Island.

5 months: flight from East Tibet, including arduous, sometimes terrifying challenges.

2nd Stage

2 weeks: Shackleton’s boat voyage across treacherous seas to South Georgia Island. Adequate food.

3 months: refugees’ exhausting trek across immense, trackless mountain wilderness. In later stages many were starving, eating leather bags.

3rd Stage

36 hours: climb across 3,000′ mountain terrain to whaling station. Adequate food.

10 days: After deadly Communist attack, spent and starving survivors climb 19,000′ over midwinter Himalayas. Survive on residual scrapings of food, bits of leather.