A Report on Trungpa Rinpoche’s Class at CU Boulder, Winter 1971

In the fall of 1970 Bob Lester, then Chairman of the Religious Studies Department at the University of Colorado, invited Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a highly ranked, Tibetan Buddhist lama, to teach a course on Buddhism to undergraduates. Rinpoche had arrived in the U.S. that spring from Scotland, landing at Tail of the Tiger (now Karme Chöling) in Barnet, Vermont, where he gave summer seminars on the teachings of Milarepa and other subjects. In August some CU professors had invited Rinpoche, then about 31 years old, to come to Boulder, and I and another student, Marvin Casper, both in our mid-twenties, had asked him if we could accompany him. So in October of 1970 the three of us moved to Colorado, initially living together in a stone cabin with a pot-bellied stove and outhouse at 10,000 feet in Gold Hill, but later moving to a modern duplex in Four-Mile Canyon just outside of town. Rinpoche’s wife, Diana, joined us after a couple of months, and they lived together in the first-floor apartment, while Marvin and I inhabited the upstairs.

The CU course was to run in the winter semester of 1971. Rinpoche appointed Marvin and me his teaching assistants, which meant helping him select readings, construct the syllabus, run the class, and conduct discussion groups. He, of course, determined the content and delivered the lectures.

At Tail of the Tiger Rinpoche had given Marvin and me pointing-out-instruction and forged a bond stronger than any I had known in my relatively short lifetime. He had recently asked us to start teaching the students who were coming to him from the coasts and elsewhere, hippies mostly, without much money, adventurous and inspired by the dharma, in general, and Rinpoche, in particular. We knew very little doctrine, but Rinpoche had introduced us to the heart of the teachings. He felt it important for Westerners to connect to the essence of Buddhism first so that they would not be dazzled and seduced by the many exotic forms promising spectacular results, a problem he considered pandemic in America at the time.

The university had a population of about 25,000, including staff and students; this in a town whose total population was about 100,000. In addition, the town had a prominent population of Seventh Day Adventists (no alcohol sold within city limits), there were no malls, and hippies were arriving from the coasts to live in the town and in the communes that constellated around it.

CU in those days had the reputation of being a second-tier school with a few stand-out departments, such as engineering. It was known to be popular with undergraduates who wanted proximity to Colorado’s ski areas, as well as the overall opportunity to play and party. So our expectations for the class were not high, and we were not disappointed. My memory was that 40 or so students sat slumped in their chairs (the kind with an enlarged arm for notepads), giving the impression of sleepiness and apathy. In fact, a few of them later became devoted students of Rinpoche. You just never know.

The room was large, stark, bare, and brightly lit, both by the overhead fluorescents and the Colorado sunlight streaming in through out-sized windows. Rinpoche wore a sport coat and tie, portly with tousled hair. He stood before the class, blackboard behind him, the Flatirons visible through the windows, rising 1,800 feet into the clear blue sky. Marvin and I sat in the front row, to the side.

Rinpoche presented basic Buddhist doctrine, but with an emphasis on the teaching of “spiritual materialism,” which he felt was particularly relevant to his audiences at that time. America was in the throes of the counter-culture revolution, protests against the Vietnam War, and the invasion of Eastern religions from India, Tibet, Southeast Asia and Japan. Think Satguru, Maharishi and the Beatles, Yogi Bhajan, Hare Krishna on street corners and in airports, Zen Beats, macrobiotic diets, of course yoga and meditation and kundalini energy and much more. We were all so naïve, ready to ape the cultures of these imports, hoping that, by adopting their to-us-exotic forms, we would enjoy some benefit or release from unhappiness. Rinpoche spent a lot of his time debunking that notion: he once told an audience, almost apologetically, “If I told you to stand on your heads 24 hours-a-day, you would do it!” A lot of the Hindu teachers preached happiness/bliss/love, etc. Rinpoche called that “love and light.”

The lecture that most stands out in my memory—because it was so revelatory for me personally and so brilliant—was the one he gave on the trikaya, a Sanskrit term that refers to the three (tri) bodies (kaya) of the buddha: the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya, which are to be understood at various levels. This was not a lecture on spiritual materialism.

Most basically, the term nirmanakaya refers to the actual, physical and mental manifestation of Shakyamuni Buddha, as well as other enlightened individuals. Nirmana is usually translated as “manifestation” or “apparition” or “incarnation.” It is the idea that one has taken rebirth many times—died and been reborn over and over again—and that this current birth is the “nirmana” or current manifestation/incarnation. The Tibetan for this term is tulku, a word applied to reincarnate lamas, so the Dalai Lama is the 14th tulku (or nirmanakaya) in his line, and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was the 11th Trungpa tulku.

In one sense we are all nirmanakayas (tulkus), because we all have been reborn many times, however the term is usually reserved for enlightened teachers who take rebirth deliberately, out of compassion and because they have taken a vow to work for the benefit of confused, sentient beings until there are no more. The rest of us unenlightened individuals take rebirth not deliberately but out of the force of our karma: habit and desire drive us forward in life and in death to continual and uncontrolled rebirth in various realms of suffering. We are fortunate to be human beings in this life—the human realm is the only one in which a being may traverse the path to enlightenment and freedom—but we may not be so fortunate in future lives. Sooner or later we will be reborn in all the realms: god realms, animal, hungry ghost, and hell realms. In fact, we experience this psychologically even during the course of a day, in which we experience the anger and panic of the hell realms, the pride and pleasure of the god realms, the hunger and sense of deprivation of the hungry ghost realms, or the stupidity, sloth, and fear of the animal realms.

Dharma is a Sanskrit word which has a number of different meanings, but here it refers first to the Buddhist teachings: the “truth” about who we are and what confusion and wisdom are, the path to realize enlightenment and release from suffering. In addition, “dharma” refers to the true action of an enlightened individual, a buddha. Dharmakaya, then, from the earliest teachings refers to the “teachings” body of the buddha: the instructions he gave to his students to help them see what is real and tread the path. Additionally, it refers to the buddha’s capacity to act in accord with what is true and real.

Sambhogakaya is a term that appeared in a later period of history and which is usually translated “enjoyment body” of the buddha. It refers to the idea that, when one has the eyes to see, there is a world of celestial beings, buddhas and bodhisattvas, dharma protectors, teachers, and embodiments of energy, enlightened and not. This world is present here, and in truth we are in the midst of the Akanistha (Above All) Heaven, but the Sambhogakaya realm is hidden in plain sight from the unenlightened, who may become aware of it only in glimpses, if at all. It is a world of beauty, power, and meaningfulness and, it is completely available to individuals who have left confusion behind, bodhisattvas on the “grounds” or stages of the path and enlightened beings or “buddhas.”

But there is another subtler way to understand the trikaya, and it is this understanding that Trungpa Rinpoche taught to us that winter day in 1971. He did it in this way.

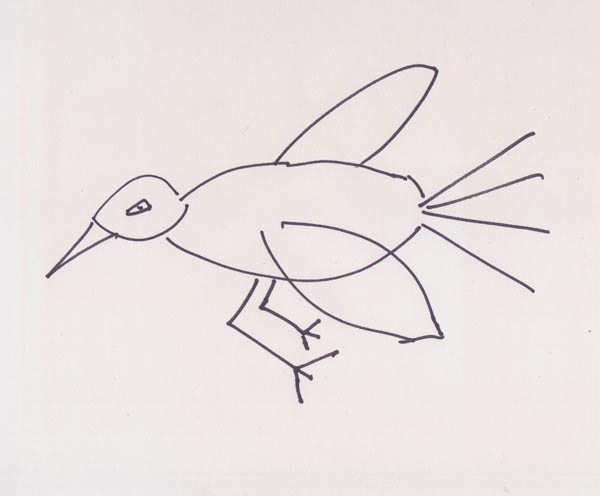

Stepping to the blackboard, he picked up a piece of chalk and drew the figure on the right: Then he stepped back and asked:

“What is this a picture of?”

Of course, no one wanted to say the obvious, and there was an extended silence, until finally some fellow raised his hand and said, “It’s a picture of a bird.” Rinpoche replied,

“It’s a picture of the sky,”

and in those six words he taught the entire trikaya.

Rinpoche was introducing us to the most profound Buddhist description of reality, as it arises in the only place and time it ever arises: here and now. It is not a metaphysical explanation of reality; it is simply a description of what arises in the moment, now, the only time we ever have.

The past and future are mental constructs. Even the present can be conceptualized, but it can also be experienced. In fact, we choicelessly experience it all the time. It is merely a matter of whether we emerge from our dreams about the past, present, and future long enough to notice and see it clearly, truly.

And in the present the six types of phenomena—sights, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile sensations, and mental events—the six knowables—arise and pass away, a constantly appearing and disappearing display, like a movie, like images passing through a mirror. These “things” do not endure, even for an instant, in the present moment, as we turn our head, as our attention shifts, as the light changes and things move, the display is constantly in motion, changing so completely and continuously that we cannot even point to something that has changed. It is a continual “presencing” as they say in the dzogchen texts, a presencing of what we call phenomena. And this display has three aspects.

First, the dharmakaya aspect. All phenomena seem to arise from and pass back into nothing. Where did that sound go? That precise visual experience with the light and the angle of view? That thought? That odor? They arose from nowhere, appeared in the midst of a concatenation of conditions, and finally disappeared into nowhere. That fertile “nowhere” is, in this first pass at a definition, a meaning of the dharmakaya, absolute reality and the “womb” from which all appearances arise and the charnel ground into which they pass away.

And yet, some thing seems to appear and pass away. This “thing” aspect is the nirmanakaya. There is a “presencing” of phenomena (the six knowables appear). That presencing is the fact of seeming appearance, the “thingness” of appearances, and it is all that confused sentient beings know, because they are not paying attention to the present moment, not noticing that nothing truly exists but is a mere “presencing.”

Confused sentient beings see the phenomenal world through the veil of static thought: one sees a chair, a person, hears a piece of music, and one is consumed with the pastness and futureness of it all, one is in relationship to it, an I/other proposition, fraught with past and future significance for “my” well being. As long as we (literally) think that other things and I exist, life must be experienced as a series of I/other problematic relationships. If the other is antipathetic to us, causes us pain and unhappiness, then we want to push it away from us: hatred. If it promises pleasure, happiness, security, etc., then we wish to pull it to us: desire. And if the other promises neither benefit nor harm, then we don’t care about it: indifference. In Buddhist doctrine, these are called “the three poisons,” and you can find them depicted at the center of the Wheel of Life, a heuristic depiction of confusion, as a snake, rooster, and pig, respectively.

But seen stripped of concept, nakedly in the present moment, in reality beyond even the present moment which can be a concept in itself, then the nirmanakaya is an aspect of the presencing, of the display, its seeming “thingness,” and it is described as the display of compassion, because it can communicate with us in the form of a teacher (an actual human being or simply life experiences which move us along our path).

And finally, there is the sambhogakaya, which refers to the aspect that, as these “things” arise and pass away, they communicate to us what they are: the redness of red, the sweetness of sugar, the cold of ice, the sadness of sorrow. It is precisely because all phenomena are arising out of nowhere and passing away into it again, because they are utterly transitory, that they can and must express their qualities, so vividly and beautifully and meaningfully. This is the sambhogakaya, and it is the realm of magic: not magic in the sense of walking through walls or reading minds (although there may be that, too), but magic in the sense of the extraordinary beauty and meaningfulness and value of this world seen nakedly, stripped of the false, ego-centered and emotion-laden thoughts/dreams through which confused sentient beings see their lives. Sambhogakaya is the world of deity sacred world. In confused world things are of greater or lesser value in terms of what they can do for or to me. In sacred world things are of value for no reason at all; this life has intrinsic worth.

And so, seen in the present moment, a bird is utterly insubstantial: a constantly changing presentation, a presencing from the ground of nothingness, coming into being and passing away so totally every instant that we cannot even find any “thing” that is coming into being or passing away. In fact, we cannot distinguish between the bird and the nothing (symbolized here by the sky), which is its womb and grave. So when Trungpa Rinpoche said that he had drawn a picture of the sky, there were two ways to take his assertion:

First pass: We are so focused on the thing that we do not pay attention to the background (temporal as well as spatial) from which it arises. Look! The bird is also a picture of the sky! Lost in concept, seeing the world through the veil of discursive thought, we have been ignoring the ground from which phenomena arise and into which they disappear. In fact, this is one meaning of the Sanskrit word avidya (usually translated as “ignorance”), the fundamental error which produces unenlightenment or confusion. Trungpa Rinpoche said that avidya means “ignoring” or not seeing (the literal meaning of a-vidya) the ground, focusing only on the figure and its significance for or against me.

Second pass: the bird and sky seem different and yet we cannot find the dividing line between them. They create each other and are each other. The bird, as it moves through the sky, is merely a recoloring of the sky in an infinite number of locations. The difference between them is merely seeming, just like an image in a mirror. In the highest tantric teachings the word “sky” is often a code word for and interchangeable with “space,” which signifies the unity of the three kayas.

In vajrayana (tantric Buddhist) practice one often recites this two-line formula, or some variation on it: “Things arise, and yet they do not exist; they do not exist, and yet they arise!” The first is what Buddhists call the “absolute truth”; the second is what Buddhists call the “relative truth.”

Finally and always, the three kayas are merely different aspects of the same thing, which is what is meant when in the texts we find the assertion that the three kayas are one. The nirmanakaya and sambhogakaya, often lumped together and called the “rupakaya” or “form body of the buddha,” are in union with the dharmakaya, the absolute body, from which in the present moment, here and now everything seems to arise and pass away.

Things arise from and pass back into nothingness: dharmakaya. Things arise from and pass back into nothingness: nirmanakaya. And as those things arise and pass away, they communicate their unique, brilliant, emotionally moving individuality: sambhogakaya.

To quote a line from Trungpa Rinpoche’s Sadhana of Mahamudra, “Good and bad, happy and sad, all thoughts vanish into emptiness like the imprint of a bird in the sky.”

“It’s a picture of the sky.”

Copyright John J. Baker 2014

This article is presented in celebration of a collaboration between Naropa University and the University of Colorado on a Buddhist Studies Lecture Series in honor of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The annual lecture brings scholars of alternating years by Naropa and CU Boulder.

John Makransky of Boston College delivered the second annual Chögyam Trungpa Lecture in Buddhist Studies at Naropa on September 12, 2014.