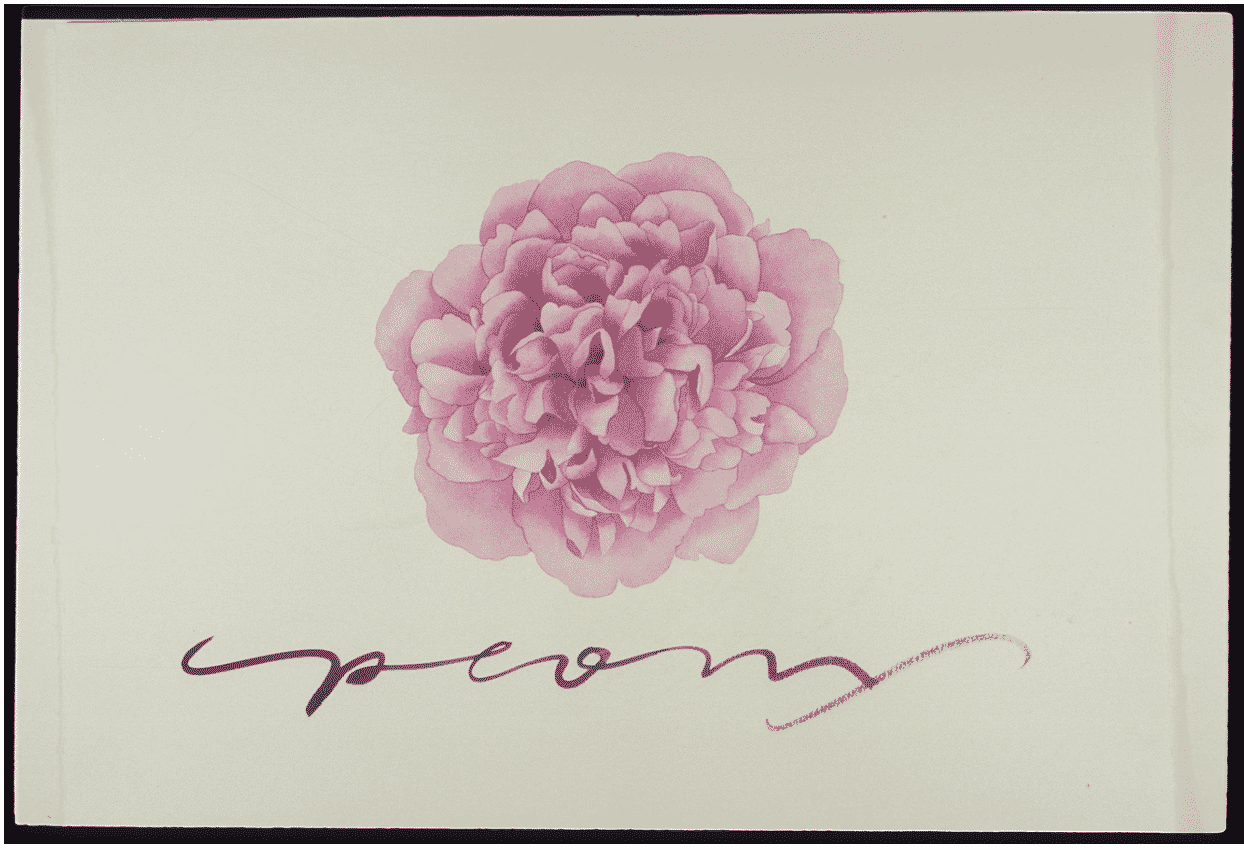

I painted a peony flower once. It was in full bloom, opened up completely. Over many hours I drew the complexity of petals with pencil and filled in each one with soft watercolor washes in myriad tones of rose, an ongoing balancing act of control and letting go in the delicate dance of pigment and water and air. When I finished the painting I wrote the word peony below with black sumi ink in a stretched out and relaxed brush script.

I painted a peony flower once. It was in full bloom, opened up completely. Over many hours I drew the complexity of petals with pencil and filled in each one with soft watercolor washes in myriad tones of rose, an ongoing balancing act of control and letting go in the delicate dance of pigment and water and air. When I finished the painting I wrote the word peony below with black sumi ink in a stretched out and relaxed brush script.

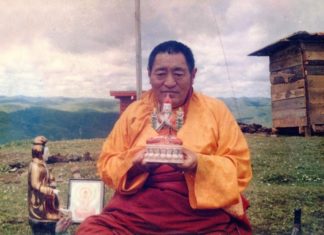

I don’t remember at what point I decided to give it to my buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa. Probably when it was complete and I could see the fullness of the creation. I wanted to give him a piece of my art as an expression of gratitude for his teachings that had opened my life. I wanted to give him something I was attached to, something that would stretch my generosity. And there was also a part that wanted to be seen.

So I made an appointment to meet with him.

This was 1986. My calligraphy studio was near the Vajradhatu administrative offices in Boulder. I rolled up the painting and walked down the street at the appointed time, entered the building and went up the central stairs to the second floor. Rinpoche’s secretary greeted and escorted me into the private office, spoke my name in introduction and then left, and it was just the two of us.

At this stage of his short and illuminated life Chogyam Trungpa was beginning to recede and contract. There was a quality of compression around him, his skin seemed darker, his eyes blacker, his presence more silent.

I stood in front of the desk where he was sitting. He looked up at me slowly, his deep liquid eyes visible over his glasses.

I bowed, still holding the package, and then said I had something I wanted to give him and I presented the painting, laying it out on the desk. He studied it silently. His body seemed small. The space in the room was thick, full, immovable. It was unbearable to just be with. I had to do something.

I walked around the desk and stood next to him facing the painting and began to talk – fast. I described how I had painted it petal by petal and then prepared to write peony and how nervous I had been at having only one shot at this. I explained that I had practiced writing the word a few times and then laid a ruler at the bottom to keep the paper steady and flat. Then I’d dipped the brush in the ink and on the first down stroke of the “p” my hand had hit against the ruler and it had felt like tripping at the beginning of running off a high dive but there was no turning back, I had to keep going, and the letters had fallen forth and landed and there it was.

I stopped talking. He was silent. We both looked at the peony.

After some moments he motioned for me to come around to his other side and I sat on a chair facing him. He slowly leaned forward. I leaned in too and our foreheads touched gently. Heads bowed together he looked up at me from over his glasses and our eyes met. In a small high voice he said slowly, “We are going to be working together for a long time.” I nodded yes.

A year later he was gone.

And I am continuing to work with him.