TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: The Sanskrit word dana, which at its Indo-European root is related to “donation,” is translated as “generosity.” Generosity, or giving in, is very important in Buddhism. Dana is also connected with devotion and the appreciation of sacredness. Sacredness is not a religious concept alone, but it is an expression of general openness: how to be kind, how to kiss someone, how to express the emotion of giving. So real generosity comes from developing a general sense of kindness.

We have to understand the real meaning of dana. You give yourself, not just a gift, and you are able to give without expecting anything in return. Usually when you give something you expect some reward. But in this case, you don’t expect anything. This is expressed in the meditation posture. When you sit in meditation, you open your arms, your front. You just open. So you are not conducting your practice in a businesslike fashion. I think the attitude of dana has a lot to contribute to the Western world. Some people think that God should give them something because they did something good for God.

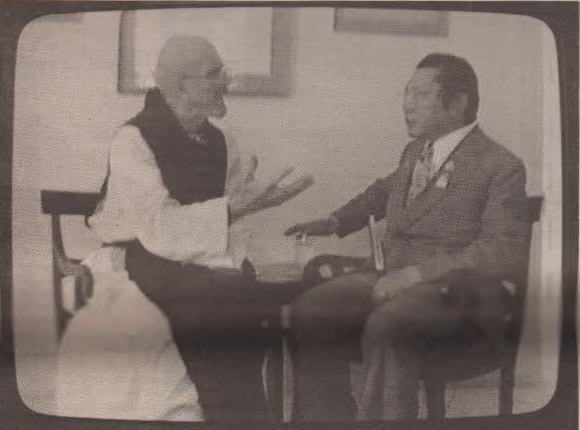

This dialogue is from SPEAKING OF SILENCE, compiled and edited by Susan Szpakowski, (Halifax: Kalapa Publications, 2005). Used by permission of the publisher. Follow this link to order the book

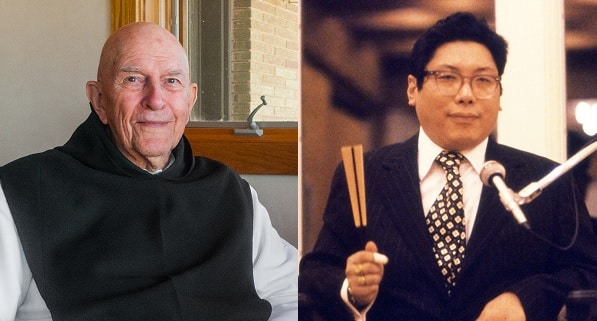

Father Thomas Keating is a Trappist monk known as one of the architects of Centering Prayer, a method of contemplative prayer, that emerged from St. Joseph’s Abbey in 1975. Keating has published 36 books, including his most recent title, REFLECTIONS ON THE UNKNOWABLE, in 2014 at the age of 91.

FATHER KEATING: Yes, that is unfortunate. But the disposition of devotion you just described is exactly what is meant by true charity in the Christian sense: it is not self-seeking, but self-giving. Isn’t it also true in Buddhism that dedication is a quality that is almost as essential as devotion for keeping us on the path? Would you say that the habit of expressing one’s dedication—the resolution to continue the meditation practice and to submit to one’s growing pains and the direction of the guru—is equally important? It seems to me that dedication and devotion are like two banks of a river. They enable both the spiritual energy and the energy of the emerging psychological unconscious to flow through. Without these two banks we would be swept away. Devotion and dedication enable us to have stable or skillful means in order to direct those energies toward efforts that are constructive, such as to use them in service to others and to further the development of one’s consciousness.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes. Those are both connected with the idea of giving up one’s ego, one’s egomania.

FATHER KEATING: Could you define “ego?” I also like to use this term, but I know that it has a precise psychological meaning that is not the same as the one you or I might use in the context of meditation. For the psychologist, the ego is an entity. Self-consciousness is crystallized into a kind of identity or individuality, which separates us from other people. Egolessness is a very difficult concept; it is not really understood by modern psychology. Exactly how would you define ego, as it is discussed in the context of Buddhist meditation?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: I think it is basically that which produces aggression, passion, and ignorance. Ego is not regarded as the devil’s work, particularly. Ego can be transformed into wakefulness—into compassion and gentleness. But ego is that which holds to itself unreasonably. In English we say “ego-centered,” for instance, or “ego-maniac.”

FATHER KEATING: Is there an ego that is un-centered?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes.

FATHER KEATING: And what name would you give to that? Egolessness?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Egolessness, yes, or shunyata.

FATHER KEATING: Let me ask a question, then. This may actually be coming from a confusion of terms, but when one has shed this egocenteredness, with its aggression and selfish self-seeking, is there not still an identity left, which may actually be very good? This identity may be experienced as self-control, goodness toward others, or even as union with God. And yet, that which is in union with God is still a self, a self-conscious or personal self. So now, is egolessness a further stage of the spiritual journey, a stage in which even a good ego, a transformed ego, ceases to exist? And would this experience be what Zen Buddhists call “no-self?”

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Well, I think now we have reached the key point. Egolessness means that there is no ego—at all.

FATHER KEATING: That’s what I thought it meant. So I’m glad to have that clarification. This is not at all understood in modern psychology.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Union with God cannot take place when there is any form of ego. Any whatsoever. In order to be one with God, one has to become formless. Then you will see God.

FATHER KEATING: This is the point I was trying to make for Christians by quoting the agonizing words of Christ on the cross. He cried out, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34) It seems that his sense of personal relationship with God, as God’s son, had disappeared. Many interpreters say that this was only a temporary experience. But I am inclined to think, in light of the Buddhist description of no-self, that he was passing into a stage beyond the personal self, however holy and beautiful that self had been. That final stage would then also have to be defined as the primary Christian experience. Christ has called us Christians not just so that we will accept him as savior, but so that we will follow the same process that brought him to his final stage of consciousness.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Well, it could be said that Christ is like sunshine, and God is like the sky, blue sky. In order to experience either one of them you have to be without the sun first. Then you begin to develop the dawn.

FATHER KEATING: Yes!

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: And then you begin to experience sunshine. First you have to have nothingness, nonexistence. And then the sky becomes blue. It’s like jumping out of an airplane. First you experience space, and then your parachute begins to open. You jump out of the airplane, which is gone by then.

FATHER KEATING: Yes. But then out of that nothingness there begins to emerge a new life, which is not one’s own, but is without a self, and is united with everything else that is.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: That’s right.

FATHER KEATING: So that’s a similar experience in Buddhism. It is also our understanding of Christ in his glory: he is so at one with the ultimate reality that he has completely merged into it.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: In order to be ultimate you have to be a non.

FATHER KEATING: A nun?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Non. Nonexistent.

FATHER KEATING: Well, that’s the ultimate of the ultimate.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes. [laughter]

FATHER KEATING: But, how would you articulate . . . Perhaps this can’t be communicated except by spiritual communion or interior enlightenment of some kind, but are there any words that point to that ineffable experience where reality is the same in oneself as in everyone else, and where action emerges out of the present moment without reflection, where one sort of knows how one should relate spontaneously, without thinking, to every moment of life?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: That is called “ordinary mind.” It is not glorious, particularly. It is so ordinary.

FATHER KEAIING: Couldn’t be more ordinary!

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Very ordinary.

FATHER KEATING: Like fanning yourself on a hot day . . . a very sacred, very profound kind of ordinary mind. Very ordinary.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Almost nothing. Not almost, even. Just so ordinary.

FATHER KEATING: So what is it that changes to bring this about? Reality doesn’t change. I suppose it is just that we cease to be a self, in the possessive sense? Self-consciousness ceases?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Everything changes. When you see sunshine, it’s a different kind of sunshine.

FATHER KEATING: Are you looking at yourself when you see the sunshine?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: The sunshine is coming to you.

FATHER KE.ATING: In other words, the sunshine is looking at itself.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes. That is why it is called “ordinary mind” in Buddhism. And often it is known as “one taste.”

FATHER KEATING: Is there not a terrible sense of loneliness or nothingness that one has to pass through in order to really taste no-self, and to then emerge into this higher unity with all that is? Isn’t it as if all reality was manifesting itself in some mysterious way, in the most ordinary things of everyday life? In other words, there’s no self to look at within. And since there’s no self, there’s no personal God, no relation to anybody else.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: I think so. I think you said it.

FATHER KEATING: How can you help someone in that state?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Bring them into ordinary mind.

FATHER KEATING: I imagine that even one’s relation to food and drink, beautiful music, and everything else would all of a sudden become the same in that sort of tunnel of experience.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Absolutely.

FATHER KEATING: So how do you live without a self? What do you do before your life opens out into a new and higher life?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: You just do it. That is what is called “old dog” mentality.

FATHER KEATING: Oh! What a beautiful expression. [Laughs]

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: He just sleeps.

FATHER KEATING: Meaning, he just exists.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes.

FATHER KEATING: A question that I’ve been contemplating myself lately is, in the state of ordinary mind, would a person suffer anything? Without a self, it seems there is no one to suffer.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: No suffering. Just lots of pleasure. Sometimes the pleasure might be suffering, but you aren’t bothered.

FATHER KEATING: If someone who was in a state of ordinary mind went through an excruciating kind of suffering, what would their response to that experience be? How would one respond to one’s persecutors or to the physical suffering that might be, humanly speaking, unbearable?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: One’s reaction would be to see space. There is lots of room, lots of space. Suffering is usually claustrophobic. But in this case, there is no problem, because the person sees space.

FATHER KEATING: For the sake of the bodhisattva ideal, would one relinquish the experience of no-self and return to the experience and sufferings of people who are still in the egoic stage?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: One proclaims; one proclaims constantly. But you are not talking.

FATHER KEATING: There’s no you.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Yes. It’s like an echo. It is often referred to as an illusion.

FATHER KEATING: One final question, Rinpoche. According to the Buddhist teaching, can this state be reached through the technology of Buddhist wisdom alone, or is there a certain point when the self has to be torn out of you by the absolute? In other words, is that tunnel I spoke of so terrible that one could never go through it of one’s own volition, unless one was kind of dragged through it by a power greater than oneself?

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: It could only come about through admiration for one’s teacher. You have to become one with the teacher and mix your mind with the teacher’s mind. Then you begin to dissolve.

FATHER KEATING: And that presupposes that the teacher must have achieved this level to begin with …

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: That is what we call “lineage.”

FATHER KEATING: That’s what lineage means in Buddhism! That’s wonderful! Rinpoche, you have provided a lot of clarification, at least for me, personally. Thank you so much.

TRUNGPA RINPOCHE: Thank you.