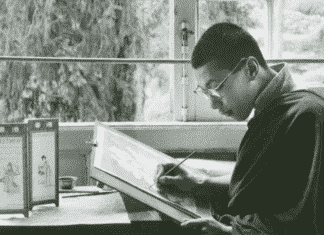

Trungpa Rinpoche had a collection of Japanese calligraphy brushes of different sizes. These he regarded as sacred implements, treating them with the care and respect of a warrior for his weapons. If a brush hair came loose, Rinpoche would carefully remove it before proceeding with the execution of a calligraphy. For ink, Rinpoche generally made use of the bottled Japanese sumi ink available in American shops. He almost always worked in black, on rare occasions in red.

Paper type and quality varied enormously. In the earlier years, Rinpoche tended to employ whatever surface was ready to hand (including at times, the wall). Especially during his frequent travels, the quality of the materials he had to work with was uneven. Some of his largest and most dramatic calligraphies were, unfortunately, done on rolls of cheap newsprint. In later years the importance of high-quality paper was better appreciated, and Rinpoche made use of fine woven and laid papers, including several varieties of Japanese manufacture. He especially favored traditional Japanese shikishi boards, gold-leafed or off-white, and many of his late works were done on them (because of the difficulty of reproducing the gold ground, no examples of this type have been included). He was comfortable working at all scales, from the surface of a folding fan to long rolls laid on the floor, which he worked over Jackson Pollock style.

Rinpoche had a considerable collection of seals, each with its own particular history and significance. Most valuable were the ancient seals of the Trungpa lineage, some of them centuries old. For these, he had a special case prepared with fitted indentations, which was carried during his travels by a trusted aide, like the black box accompanying a President. Woe if it should be misplaced! The simplest of the seals was the Sanskrit EVAM, traditional seal of the Trungpa tulkus, which he eventually passed on to his American regent, Ösel Tendzin (see below). Larger traditional seals, one of which was a gift from the emperor of China to the fifth Trungpa in the early seventeenth century, are in Tibetan or Chinese seal script. Inevitably, Trungpa Rinpoche added to the collection of seals he had inherited from his predecessors new ones of his own design.

Prominent among these are the large and small scorpion seals. The scorpion is a symbol of sovereignty and command—once one has been stung by the scorpion there is no undoing it. Rinpoche used the scorpion seals on calligraphies embodying themes connected with the Kingdom of Shambhala. The new seals were manufactured initially in hard rubber, later, traditional ivory or stone ones were made, and Rinpoche had one scorpion seal produced from meteoric iron.

Rinpoche was partially paralyzed on his left side, the result of an automobile accident. It was difficult for him to sit in “warrior posture,” or seiza, the traditional Japanese kneeling posture for calligraphy. When working on a small sheet, he would sit at his desk. Such was the case when he calligraphed names for the traditional refuge and bodhisattva vow ceremonies; these were done on 8 1/2 x 11-inch specially watermarked bond paper, sometimes over one hundred at a time in rapid succession. On these occasions a small assembly line of assistants would be on hand to help seal, remove for drying, and order the sheets for the ceremony which Rinpoche would perform, later the same day or on the day following. When executing larger calligraphies, Rinpoche stood at a table. This may have been specially set up in the sitting room adjoining his downtown office; in later years, it would more often have been the dining room table at the Kalapa Court, Rinpoche’s large residence on “the hill” in Boulder, Colorado.

Gently, but with great conviction, the brush would descend to the paper and make its first dot. Often Rinpoche would pause the brush on this first mark, as if waiting for the calligraphy to be born from its seed.

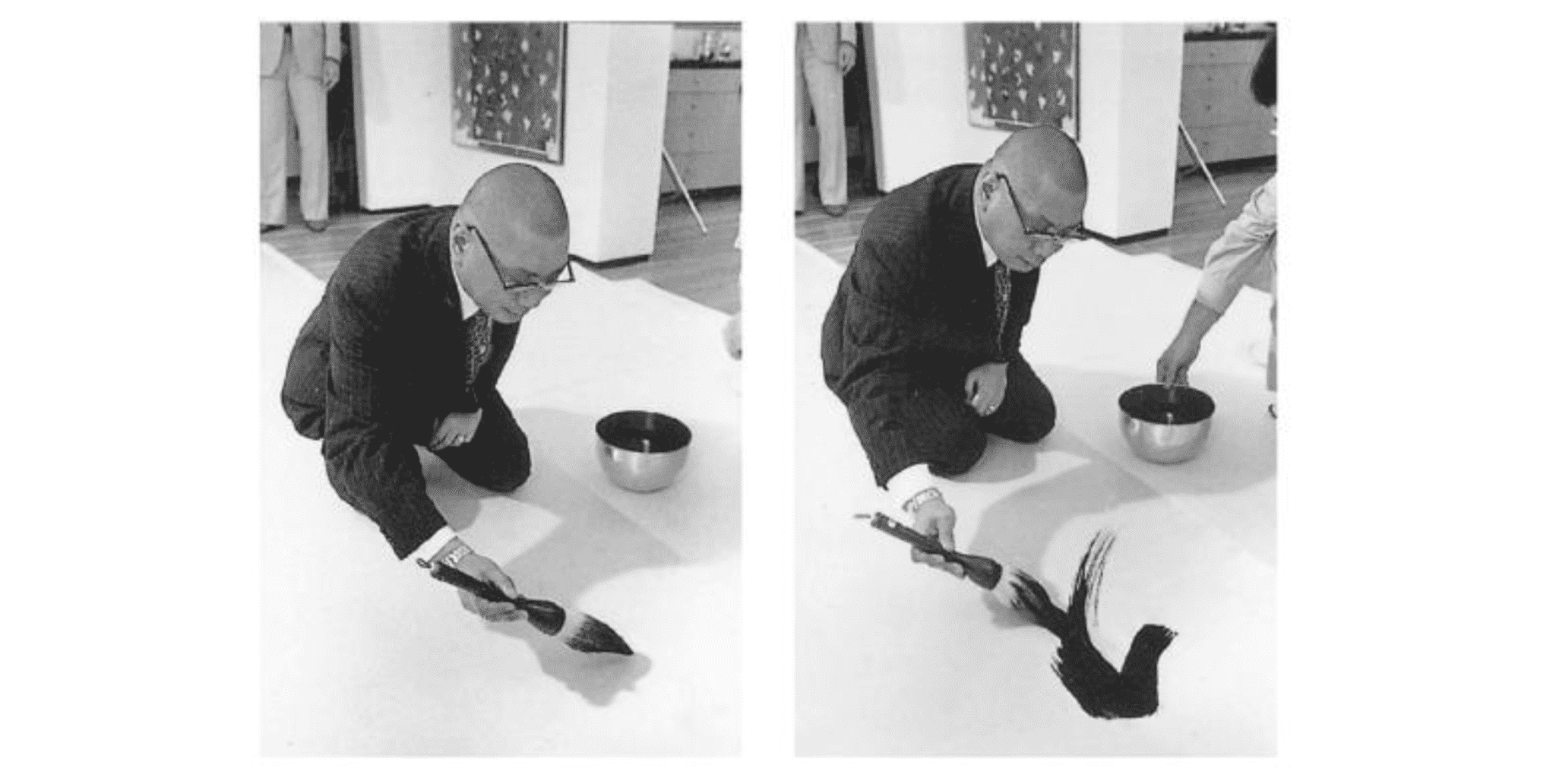

When about to execute a calligraphy, Trungpa Rinpoche would seem for a few moments to be in a state of absorption, often accompanied by a gesture of repeated dipping of the brush into the ink and smoothing the brush hairs against the side of the ink bowl. Then he would raise the brush, while gazing intently at the white space of the paper before him. In this second, onlookers could feel an arresting of habitual thought patterns as space and time crystallized into a pure, undivided moment. Then, gently but with great conviction, the brush would descend to the paper and make its first dot. Often Rinpoche would pause the brush on this first mark, as if waiting for the calligraphy to be born from its seed. Then the brush would start to move, in a continual forward flow free from hesitation or strain.

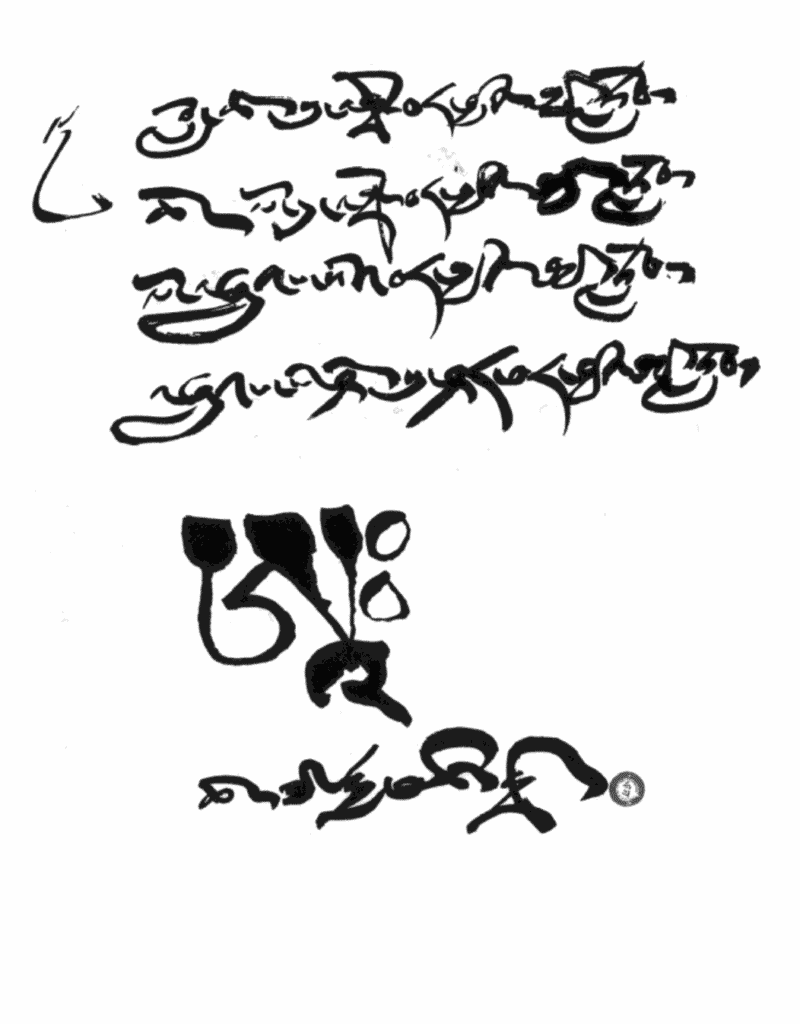

Typically, the initial one or two strokes of a calligraphy by Trungpa Rinpoche have a gentle deliberateness, evoking a sense of mindfulness and precision; then there is a crescendo, expressed in a greater speed of execution and a sense of leap or abrupt sword; finally, a “follow-through” stroke both completes the gesture and lets go of it. This pattern can be seen in many of the works, abstract as well as literal.

After a moment of inspection, Rinpoche would set down his brush and select a seal. Then, as an assistant held firm the container of thick scarlet ink, he would ink the seal and apply it definitively to the paper, pressing hard with a slight rocking motion to ensure a sharp impression. Now the assistants would hold down the paper as Rinpoche pulled the seal off with a pleasing snap. For a brief moment, all would admire the newborn, completed artwork, before carefully removing it to a nearby surface to dry.

With a few exceptions, Trungpa Rinpoche worked in black on white or black on gold. A third focal point of color is provided by the brilliant red of the seal. His use of seals frequently went beyond the simple function of identification, becoming an active element in the composition—multiple impressions, impressions turned at different angles, or masked so that only a portion of the seal appears.

As with his use of seals, Trungpa Rinpoche also signed his work in a variety of ways. His earlier calligraphies are usually signed simply with his own name in Tibetan: Chokyi Gyatso ne tri (“written by Chokyi Gyatso”). Meaning “Ocean of Dharma,” which in Tibetan often contracts to Cho-gyam, this is the “dharma” or religious name that Rinpoche received in childhood after his recognition as the eleventh rebirth in the Trungpa lineage. He rarely uses “Trungpa” to identify himself, and never “Rinpoche,” an honorific meaning “Great Jewel” that is used for all tulkus. He at times uses other titles, such as Dorje Dzingpa (“Vajra Holder”), a high distinction bestowed on him by his Holiness Gyalwang Karmapa XVI, head of the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Later works, representing Shambhalian themes, are often signed with his Shambhala warrior name, Dorje Dradul (”Indestructible Subjugator of Enemies”) or Sakyong Dorje Dradul (The Earth-Protector Indestructible Subjugator”). Sometimes he employed the English initials “DD of M,” standing for Dorje Dradul of Mukpo, his family name, derives from one of the six ancient clans of Tibet. Trungpa Rinpoche traced his ancestry to the most famous Mukpo of all, the legendary warrior-king Gesar of Ling.

Rinpoche frequently equated brush and sword. “The brush is tempered and folded and beaten as a good samurai sword…In conquering from the East, brush stroke is a weapon…you realize that brush cuts and sword paints.” Trungpa Rinpoche wielded his calligraphy brush as a sacred weapon. For him, the brush was a sword of nonaggression, a proclamation of transcending neurotic attachments with the hope that it may contribute in some degree to the accomplishment of Rinpoche’s dharma warrior-king vision for a world of peace, courage, and beauty.