Part One: A Costly Delay at yak Monastery

May 26, 2013

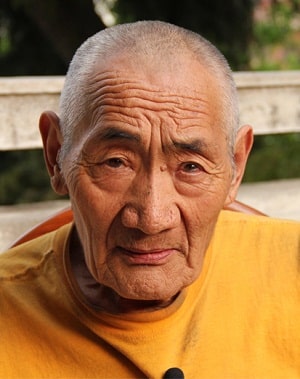

In the late winter of 1959, after discovering that Surmang had been overrun by Chinese troops, Trungpa Rinpoche visited Khamtrül Rinpoche at his nearby monastery. The two lamas spent many days in private conversation. Presumably (Yönten was not privy to the details) they were discussing their options and making plans to leave Kham. Meanwhile, yak Tulku requested that Trungpa Rinpoche come to his monastery to bestow the Rinchen Terzöd empowerments, a process that takes many months to complete. Trungpa Rinpoche agreed and Yönten joined him at yak Monastery where he found himself fully occupied both in and out of the shrine hall. “Daily I prepared Rinpoche’s clothes for the day … [after which] I did everything, and was busy day and night …”

Yönten recalls Khamtrül Rinpoche’s visit to yak Monastery during the empowerments. The two lamas spent several days together discussing escape plans. Their destination, even at this stage, was India. The plan was for the two lamas to escape together. Khamtrül Rinpoche implored Trungpa Rinpoche to leave with him at once, and not to wait until the Rinchen Terzöd was complete. yak Tulku insisted that Trungpa Rinpoche stay at yak Monastery and continue the empowerments.

After much discussion, the two lamas parted ways. Trungpa Rinpoche stayed at yak Monastery, and Khamtrül Rinpoche left for Inida. Yönten pointed out that Khamtrül Rinpoche “had a very easy time” on his escape, and that he was one of the last lamas to make it to India from Kham with all of his baggage. When Trungpa Rinpoche finally left Kham, the Chinese army had a firm grip on much of Tibet and the going was much more difficult. Yönten expressed some bitterness towards yak Tulku, his “pushiness” insisting that Trungpa Rinpoche continue with the Rinchen Terzöd, even though the Communist troops were known to be on the hunt for him.

At this time there was violence and conflict throughout Kham as the Chinese strove to put down the revolt. They seemed to be everywhere, and had even been present around yak monastery during the transmission. Yönten remembered that “Chinese soldiers were all around, watching …”

As Yönten related his memories of the Rinchen Terzöd, our translator Ani Jinba occasionally broke into giggles, finally saying that she couldn’t believe how relaxed the Tibetans had been, just going on with things in a very relaxed way, with the Chinese army breathing down their necks.

Following the Rinchen Terzöd, Rinpoche became so ill that there was fear for his life. Yönten remembered the large beam that cracked in Drölma Lhakang’s shrine hall, and that it was taken as an ominous sign. Drölma Lhakang, which was Akong Rinpoche’s monastery, was very close to Yag. Yönten also recalled that around this time Rinpoche had a dream, that “monkeys were running all over Surmang.”

When Trungpa Rinpoche finally left with a small party towards central Tibet and eventually India, Yönten stayed behind to pack up Rinpoche’s possessions, planning to catch up with the escape party en route. With all the conflict, the communist troops everywhere, the atmosphere was dark with menace. At one point Yönten became “frightened by a huge fire” at Drölma Lhakang, only calming down “when the nuns told me that the fire was for protector offerings…”

The packing done, “I left at night with the horses and provisions … [catching up with Rinpoche’s party] where they had camped at a pass near Shabye Bridge, unable to continue because the Chinese held the bridge …”

Part Two: Heated Debate on the Plateau

June 4, 2013

Although the escapees had earlier heard news that Lhasa was under attack—later confirmed by Rinpoche through a mirror divination—up to June 1959 they were still heading for Lhasa, some hoping against hope to find refuge there. But in early July, after they heard from travellers that the road to Lhasa was blocked by Communist troops, Rinpoche led them southwards over the Nupkong La pass and down the Alado Valley. They were now heading towards India.

Yönten described the Alado Valley as “huge,” yet it was clogged by masses of frightened refugees and dead or dying animals. He recalled the dead yaks blocking their path, and the pervasive putrid smell. The further they went the more impossible the going became, until they had little choice but to detour again, climbing up a perilous track to a 17,000 foot mountain plateau. Yönten recalled that the mountain was so steep that they couldn’t see where a horse, which had slipped off the track to its death, had landed.

In Born In Tibet Rinpoche described the Queen of Nangchen, and that he was surprised at how tough she was, a cheerful woman who preferred to walk through the snow up to the plateau rather than ride. In one of the most heart-rending accounts we heard in Kathmandu, Yönten told of meeting the Queen years after the escape, when she was 50. Her entire party of 60 people had been captured by the Chinese, while she herself had been imprisoned and so horribly tortured that her back had been broken, and she now walked bent low from the waist.

Rinpoche led the group of refugees to a secluded valley on the plateau, where they set up camp and settled down to await developments. Their location was finely positioned, high above two major travel routes yet out of the maelstrom in the valleys below. From here they could gather information as events unfolded while keeping their options openwait in place for the violence to die down, return to Kham, go on to Lhasa or head south to India.

With the camp set up, Yönten headed down with pack animals to the Nyewo Valley, the next valley to their south, for provisions. A 9,000 foot climb, the trip took him a full day each way. It was midsummer now, with frequent rain. At such a high altitude it was cold, but Yönten said that no snow fell. Wild animals were everywhere, including large brown bears, which began to maraud among the horses and mules. During Rinpoche’s retreat, he could hear them moving around his tent.

Yönten told of rumours among the refugees, that along with the bears there were drewös—non-human miraculous manifestations, demons making obstacles for the journey. Although no-one saw them, Yönten said that he’d seen their tracks, a print like a human’s but considerably larger, like the fabled yeti. When we questioned him further on the subject he must’ve sensed some skepticism and laughed, saying that he didn’t care whether of not we used the story.

He recalled that they were on the plateau for a full month, in the course of which many lamas came to visit Rinpoche. Yönten noted that their reports of violence and destruction in Central Tibet confirmed Rinpoche’s early decision not to attempt the journey to Lhasa.

He also talked with some emotion of the debate within the lama’s group. Rinpoche describes the debate in some detail in the book, the competing viewpoints, his bursar Tsethar’s grumblings and criticisms, Akong Rinpoche’s older brother’s complaints about Rinpoche’s lack of a clear plan.

During his Crazy Wisdom Seminar, given in Jackson Hole in 1972, Trungpa Rinpoche outlined Padmasambhava’s approach to working with people. He would just “let the phenomena play… Let the phenomena make fools of themselves by themselves” [Crazy Wisdom, p. 51-2] They can’t be conned or talked around with logic, words, one can’t prove or explain something. Rather, Padmasambhava allowed the “totality of the logicalness of the situation” to speak for itself.

There are strong indications that up to this point of the journey, Rinpoche had been following this strategy. He’d been clear for some months that India must be their destination—certainly since they’d heard the news that the Karmapa and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche had fled there. Yet he’d left things open, waiting to see how events unfolded, willing to entertain other options, allowing the space for others to voice their views without imposing his own, waiting for the hard logic of events to make itself heard.

Following his retreat on the plateau, though, and from the latest information they had, Rinpoche was very clear that their “only hope,” as he put it, lay in trying to reach India. Yönten recalled that a secret mo was cast, and this too supported the India plan. Rinpoche now said to the others that it must be India, and dismissed other options when they were put to him. With this in mind, and knowing that a hard journey lay ahead, he instructed Tsethar to begin selling possessions—which at first he flatly refused to do.

Yönten was “shocked” at Tsethar’s refusal to follow Rinpoche’s orders. He recalled that during an especially heated debatea “fight,” he called itRinpoche was silent. Akong Rinpoche was also quiet, but crying, while the undecided Yak Tulku also said nothing. Tsethar the bursar, perhaps recalling Surmang’s history, when Mongols and Chinese warlords wreaked destruction and then left, insisted that they should return to Kham. He said that there was no way they could reach India. He was, said Yönten, “very pushy.” Akong’s older brother agreed with him, seemingly prepared to follow him.

On this occasion, with Rinpoche silent, just sitting there, Yönten felt that he had no choice but to speak up on Rinpoche’s behalf, to be an intermediary, to push back. He reminded the others that the only reason that they were all here was because of Rinpoche’s leadership and escape plan. He said that even though the chances of getting to India were very small, it was insane to try to go back and that, come what may, he himself would try to get Rinpoche to India.

As Rinpoche wrote in Born In Tibet, with the issues unresolved, they decided to split up, the two groups taking different ways. Perhaps out of discretion Rinpoche left unclear the route Akong Rinpoche’s group planned to follow, or why, except to say that they had simply chosen a different path over the mountains.

Yönten’s memory of the route taken by Tsethar and Akong Rinpoche’s group was much more specific. He said that they had in fact decided to retrace their steps, to return to Kham. They travelled eastwards for about two weeks, until they ran into Communist troops coming towards them, from the direction of Kham. They hastily turned around and, knowing Rinpoche’s plans, found a route across the mountains to Rigong Kha, their baggage train more or less intact. Rinpoche had left the area some time before.

Yönten said that the Rigong Kha villagers had never seen so many yaks and horses, all of which had to be abandoned there as Akong’s group prepared for their own trek. As we know from Born In Tibet, they finally caught up with Rinpoche in the mountain wilderness, continuing on under his leadership, heading for the Brahmaputra.

Part Three: Into the Broad-running Current

19 June 2013

After dark on the evening of 14th December, 1959, as soon as the newly-made coracles had dried out, Rinpoche led the refugees down the mountain on their first attempt to cross the Brahmaputra. The going had been more difficult than expected, the coracles trickier to handle. In the early hours of the morning, Rinpoche realized that there wasn’t enough time to cross the river and hide the coracles before dawn broke. He led the exhausted, starving refugees back up the mountain, where they hid themselves and settled down to wait until they could make another attempt.

During the morning the refugees talked quietly among themselves about the fact that Rinpoche was personally leading them, was going to try to get everyone across the Brahmaputra. He’d made no announcement to this effect, nor did he mention his decision in Born in Tibet. Once the coracles had dried out, when darkness fell he’d simply led the refugees down the mountain.

Fifteen year-old Palya had been taken by surprise—along, it seems, with just about everyone else. They assumed that Rinpoche, the lamas and their attendants would cross the river first, leaving the rest of the party to follow on behind as they could. People knew all too well that their leaders, Rinpoche in particular, were the Communists’ primary targets, their chances of surviving capture small. It was likely that most people wanted them to cross first, such was their regard for the lamas. It was, though, deeply heartening to know that Rinpoche would be with them.

If Palya was surprised by Rinpoche’s unspoken decision, Yönten was appalled. Ever since his uncle Karjen, Surmang’s general secretary, had passed on to him the responsibility for getting Rinpoche safely to India, he’d proven himself to be his stalwart, sometimes fierce protector. Rinpoche was his charge—as he said, more precious to him than his own life. From his years of travel in Kham’s bandit-infested terrain, he had a solid, earthy feel for the perils ahead. It was obvious to him that trying to get a mass of refugees down the mountain, along the shore and across the river—with all the multiplied chances of discovery their large numbers meant—would put Rinpoche’s own life in grave jeopardy. His worry about Rinpoche’s safety now brought to a high flame, Yönten begged him to reconsider. Rinpoche and the tulku group must go first and go alone. Any other course would, he said, be a “big mistake.”

Rinpoche heard Yönten out but was adamant. He would do his utmost to lead everyone to safety. No one was more aware of the risks. After all, even before they’d left Drölma Lhakang eight months before, he’d implored the lamas joining him to keep their numbers small to better their chances of escape. But Rinpoche knew that if he was to cross first, the risks faced by the hundreds of refugees left behind would be greatly amplified. Without Rinpoche’s physical presence to steady and inspire, there’d already been disturbing signs of the breakdown of discipline. There was no hierarchy of command he could trust to take over from him. What’s more, there was a good chance that, out on the broad river under a full moon, even one or two coracles would be seen by sentries on the shore. After one coracle was spotted, everyone’s chances of escape would evaporate.

Yet the issue for Rinpoche may have been much simpler, even choiceless. From everything we’ve learned, Rinpoche was not at the eleventh hour going to abandon people who’d asked to join him, for whom he’d accepted responsibility and whom he’d cared for and brought all this way, not even at the cost of his own life.

Rinpoche spent most of 15 December higher up the mountain where he’d climbed with the monk Urgyan-Tendzin, sitting in the warm sun while they reconnoitred the terrain for a crossing point. Near dusk they returned to their camps, hefted up their packs and left for the lower campsite where many of the refugees had ended up. He was dismayed to find that, in spite of his strict instructions, they had still not finished packing. There was a further delay when his attendant chased and beat a young boy he thought had stolen Rinpoche’s tsampa. When they finally left, time was again running out.

Some time after midnight, they’d made it down the mountain to level ground and were wending their way along the river bank. Rinpoche went from group to group, quieting and encouraging the frightened refugees, always exhorting them to move on, to move faster. At one point he had to run after stragglers heading off in the wrong direction. He’d again had to combine the roles of general and sergeant, inspiring and directing while keeping people together and moving forward.

Approaching the crossing point, Rinpoche spotted a man in Kongpo dress hiding behind a thorn bush. When Rinpoche looked directly at him, the man disappeared. A few minutes later he saw another man in Kongpo dress, but this one was carrying a rifle and had a lighter complexion, suggesting to Rinpoche that he might be Chinese. It was an ominous sign.

Just as the full moon rose, Rinpoche wrote, his group “reached the river and were the first to embark.”

Yönten’s memory of those super-charged minutes was detailed, and gainsaid the mood of the leisurely boarding of an ocean liner. Rinpoche continued to walk up and down the bank among the refugees, talking to them, helping them to organize around their coracles, calming themall the while ignoring Yönten’s worried urgings to board his coracle and leave. Finally, with Yönten pleading “Let’s go! Let’s go!” and, from the sound of it, almost physically bundling Rinpoche into the coraclethey climbed in, pushed off from the bank and paddled out into the broad, strong-running current …