Fabrice Midal: Is there a link between how Chögyam Trungpa approached elocution and how he taught other ways of working with a form as a path?

Carolyn Gimian: The basic approach to elocution is very similar to the approach that Chögyam Trungpa took to many other disciplines — from how he taught marching to the vajra guards, or the Dorje Kasung, to how he taught Dharma Art. When Rinpoche encouraged his students to wear a suit and tie to a formal event or taught them about oryoki, the monastic style of eating in the shrine room, his reference point was always how form can evoke wakefulness, rather than basing his approach on moralizing or a small minded sense of self-improvement.

With many of the secular disciplines that Trungpa Rinpoche presented, it seems to me that he took an approach similar to what one sees in the traditional practice of various Japanese “dos” or ways — such as the way of archery, kyudo, or the way of tea, chado. I think he is possibly the first Tibetan Buddhist master to take this approach and to grasp its profundity and application in modern circumstances so fully.

From the perspective of vajrayana Buddhism, one could say that he was transmitting the teachings of mahamudra very fully through the various disciplines that he presented. I certainly have experienced this in terms of elocution: the quality of suddenness and penetration and the sense of speech as mudra, a gesture or symbol, that fully embodies and expresses the aliveness and the utter presence of reality. It also expresses simplicity at the same time, however, and emptiness that is full of presence. It’s hard to know how to put these things sometimes.

Trungpa Rinpoche showed that there are many parallels between Zen Buddhism and Tibetan tantra, and places where they intersect. More interestingly, he was able to see beyond any Tibetan chauvinism and to appreciate that he could learn from the Zen perspective; he could take from that, with a great deal of respect, to help him bring his own tradition and teachings into the West. I think that is part of what these disciplines are about, such as his approach to elocution and poetry, his work with the Dorje Kasung, his love for kyudo and calligraphy done with brush and ink.

When Rinpoche started teaching me elocution, I had been studying tea ceremony for a few years with Okusan, Mrs. Shibata, the first wife of Kanjuro Shibata Sensei, the great Kyudo master. Trungpa Rinpoche had asked Mrs. Shibata to teach tea ceremony to a group of people in Boulder, and a friend of mine, who is now an advanced student and teacher of tea herself, Martha Rome, convinced me to join this group. Mrs. Shibata used a very traditional approach with us, which was that she demonstrated how to do things without much verbalization or extensive explanations. Then you would try to imitate what she was showing you and she would correct you and show you how to do it again and again, until you got it right — or close to “right.” When she corrected you, it was very on the spot and without a lot of conceptual reference points. You just knew you were doing something wrong and you had to keep redoing a particular thing over and over until you got it “right”, often not really understanding what the problem was.

After I had been studying tea ceremony for some months, I practiced and tried hard to learn while Sensei was away in Japan. When she came back to Boulder, I expected her to be pleased with my progress, but instead she pounced on me mercilessly the first time I did the tea ceremony with her, and she kept me kneeling in great pain for what seemed like a very long time, correcting me over and over and making me redo everything countless times. I felt completely humiliated, but also somewhat purified and purged.

I had a very similar experience when I was learning elocution with Chögyam Trungpa, and after awhile it dawned on me that Rinpoche was using a similar teaching method to present elocution. I found that the better I got, the more ruthlessly he went after me. One night I remember he made me say the word “thoroughly” in Oxonian over and over again, bringing me to the point of tears. I thought I was going to break down. I tried to tell him that I couldn’t do the elocution, and he just told me that everything was okay and that I should continue.

At that moment, I felt completely trapped, and I realized that I either had to give in to him and the discipline or I would go shrieking out of the room and never return. I was on retreat in the middle of nowhere with him, so my escape didn’t seem very feasible — otherwise, I might have tried it! Instead, I just gave up. After that, I started to learn in a new way and it seemed that we could go on and on and on and it was okay. I stopped trying to control the whole thing.

In retrospect, it was some of the best, most precious training that I received from him. I know that people studying other disciplines with him had similar experiences. So there are a lot of parallels.

On the other hand, I think it’s important to recognize that there is a particular magic or particular transmissions that are unique to each discipline, and they can’t be mixed together. Different disciplines may lead to the same realization, but they are distinct and can’t be interchanged with one another. That’s part of the profundity. In vajrayana we don’t say “All is one.” Rinpoche sometimes said it was more like “All is zero.” That makes some sense to me. You start from the same place, and maybe you reach the same destination, but you have to make the particular, individual journey.

Fabrice Midal: Is elocution connected with Chögyam Trungpa’s teaching on the sambhogakaya aspect of his work, the energy? Does relating to this world help us to join heaven and earth, body and mind?

Carolyn Gimian: I don’t tend to relate to elocution from this point of view, but yes, I think it does relate to the sambhogakaya teachings, if by that you mean the energy of enlightenment, the way that wakefulness is expressed or communicated. Chögyam Trungpa did talk about elocution as purifying the level of speech, and he said that when you pay attention to your speech and practice good enunciation, good elocution, then automatically you will sit up straight and be mindful. So he spoke about how speech can affect both body and mind, and he did, I believe, talk about how speech joins the levels of body and mind. So this is very much like the man principle joining heaven and earth.

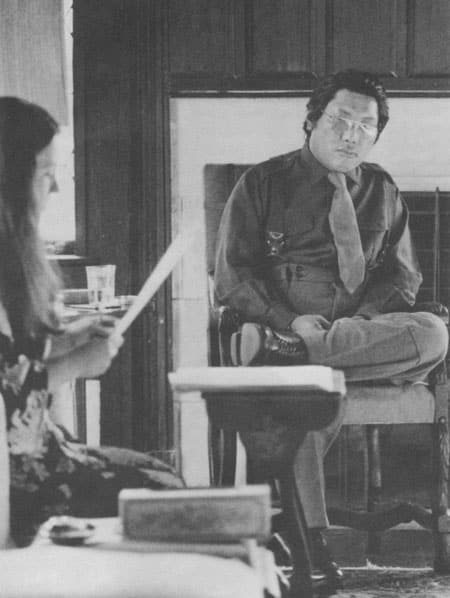

Trungpa Rinpoche recites from The Elocution Home Study Course, circa 1985

https://media.s3bubble.com/embed/aprogressive/id/ROag75310

In my own experience, this really is true. If you are paying attention to how you speak and how others communicate, you will find that you are paying attention altogether to the environment, to how you sit or stand, to how you hold your hands, to how you look at people — all those things. And at the same time, your mind is very supple and taut at the same time, expectant, waiting. So there is a lot of wakefulness.

Fabrice Midal: Why do you think Chögyam Trungpa introduced elocution in 1983? Is there a reason why he did it at this time of his life?

Carolyn Gimian: It would be presumptuous for me to presume that I know exactly what Rinpoche was doing or why he did things at a particular time. However, I do have some theories about it.

In fact, I think he said a few things about this. Once, when he was presenting elocution to a group of people, he talked about how he had started by working with the level of mind, when he first taught meditation. When he first came to America, the people who were attracted to him, by and large, were not very interested in dressing well or getting rich or other material things. They were involved, many of them, with a political or cultural or social protest against the way things were in American society and they were going against the status quo, in terms of how they dressed, what they wanted to do with their lives, etc. This made them open, perhaps, to the Buddhist teachings but somewhat sloppy in the way they conducted themselves at times. So Rinpoche started with their minds, which meant that he wasn’t punitive or critical, but he started with something that they could relate to right away. So he gave meditation instruction that was actually quite advanced, where he talked about a sense of being and mixing your mind with space. This approach spoke directly to his audience.

Then he worked on cleaning up people’s acts, so to speak, dealing with the level of body by encouraging people to dress well and create order and elegance in their environments. That was part of his introduction of the Shambhala teachings. Then, he finally worked with the level of speech. He talked about how it would be quite strange to see a beautiful woman, beautifully groomed and dressed, who barked like a dog. That was an example he sometimes gave of the need for good elocution.

Also, when Rinpoche introduced elocution in 1983, it helped to create a further sense of formality around him and to bring people’s attention to him and the space that he was creating in every situation. He made it almost impossible for people to have any casualness around him. I think, in retrospect, that was very very helpful, because at this time, the last few years of his life, he had some very important things to transmit to people and he really needed their full attention. What he was transmitting was not necessarily a message that he put into words, but it was, at this point in time, much more of a dharmakaya or ultimate message about how to be. He really needed space and attention to make that transmission. Forcing people to speak mindfully and stopping mindless chatter was part of creating that space.

Then he also introduced other activities, or disciplines, that frustrated people’s habitual patterns of behavior and thought around him. He would ask people to sing with him or for him, usually the Shambhala Anthem or another song that he had composed. And he would often ask people to sing this over and over again, outrageously high or sometimes in a Scottish accent. On the one hand, it was just quite strange — unsettling in some way. On the other hand, again, it brought your mind right into the moment. There was nowhere else to go.

In the last year or so of his life, he actually progressed beyond elocution to silence. In the last few months before he became ill, people often sat in a room with him for hours at a time with very little being said. He somehow made it impossible to talk at all. And he would stare very intensely at you sometimes, which I have heard is a form of the guru’s blessing, when he stares at you like that. I think this was actually a very profound period and a time when he gave ultimate transmission of some kind. But not everyone felt that way. For me, it seemed like the natural progression or outcome of elocution.

In general, I think that he was always planting things in people to flower later, if we continue with our practice and really exert ourselves in meditation. I firmly believe that one could attain complete, perfect enlightenment by practicing elocution — as well as through the sitting practice of meditation or other disciplines that Chögyam Trungpa taught. That was part of his genius as a mahasiddha, that he could embed any activity with total sanity.

© 2018 by Carolyn Rose Gimain

This article was originally published on the Chronicles on August 31, 2005