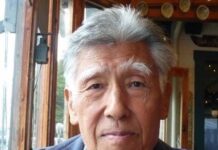

Peter Lieberson passed away yesterday, April 22, 2011 in Israel, at the age of sixty-four. Peter was a close student of Trungpa Rinpoche, an early director of Shambhala Training, a prominent teacher within Khandro Rinpoche’s community, and a renowned composer. He is survived by Ellen Kearny, his wife of many years, and by their daughters: Katherine, Christina, and Elizabeth. He is also survived by his third wife, Rinchen Lhamo. Peter is predeceased by his second wife, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson.

Tribute to Peter Lieberson

By Barry Boyce

July 15, 2011

Peter Lieberson cut his teeth as a dharma teacher in Boston. It’s a notably tough town. It intimidates. Books have been banned there. Street toughs from Southy and the Dirty Dot (Dorchester) are not to be messed with. Fenway’s Green Monster has made visiting leftfielders look silly. The Boston Brahmins up on Beacon Hill look down their aquiline noses and reduce the hoi polloi to nothing with a withering stare. Harvard is older than America, and way smarter too, so they will tell you.

The Boston Dharmadhatu was already venerable in the late seventies. A proud collection of early pioneers, we wrangled people into the dharma one rigorous nyinthun at a time. Trip cutting was the order of the day (and good thing too; there were lots to be cut). Honest, cynical, no bullshit dharma was our stock in trade.

Into this fray waltzed Peter and Ellen with the lofty message of cheerfulness and confidence. They did not receive a love and lighty reception. They were ripped to pieces. Trungpa Rinpoche sent them in to shake things up, and shake they did. He loved it that way, but it was vitally important that the shakers and the shakees get shaken together. That’s how it went, and Peter and Ellen came out the other side. They became an integral part of the community and Shambhala Training flourished. Most people of Peter’s parentage would need to strain to behave as a bloke. It came naturally to Peter. He carried his dignity lightly and with ease. He was musical in all things.

When Peter gave up a tenure-track position at Harvard to move to Nova Scotia to head up Shambhala Training, I thought he was crazy. And probably he was. In a good way. Nova Scotia was tough in its own way. He was once hit in the head with a golf ball by Jeff Rosen, who took some credit for a shift in Peter’s musical sensibilities. I first came to know Peter as a golfer when I was living in Washington. He visited to teach Shambhala Training and liked to play on the little course in Rock Creek Park. I was surprised he was doing this during the day on Friday when he had a program to teach in a few hours. He quoted Trungpa Rinpoche’s injunction that preparing should include “enjoying refreshing activities.” I’ve followed that dictum ever since.

Peter and I used to play golf and talk opera, around the time he was working on Ashoka’s Dream. He borrowed some of my Puccini and Verdi. I used to love to watch Peter’s swing; he had a musician’s sense of timing and when it all came together he hit the ball a milea thing of exquisite beauty. But if his timing was just a little bit off, he

would have the most wicked hook I ever saw, with the ball careering left in a dramatic arc, deep into the woods. His disdain at such a hideous shot quickly turned to humor. Ever the gentleman.

For my fortieth birthday, he gave me his copy of 5 Simple Steps to Perfect Golf by the illustrious Count Yogi. He inscribed it, “With my very best wishes for success on the path towards perfect golf®.” Sincerely, Count Yogi. Funny, yes, but Peter had earned the right to use that name. It’s how I think of him now. So sad to see him go.

-Barry Boyce, Halifax

Peter Lieberson

I first heard about Peter in 1977, when I was asked to host a gathering of musicians at my apartment in Berkeley to hear a talk about meditation by a composer who was visiting the Bay Area. I was a new practitioner at the Berkeley Dharmadhatu (as our centers were called before we renamed them Shambhala Centers), and I was very curious to meet another musician who meditated.

A couple of nights before he gave the talk at my house, I met him for the first time at a talk he gave in the lounge of the San Francisco Conservatory to a small group of music students. He began the talk by thanking Alden Jenks, a composer on the faculty, and saying that he and Alden had spent “an interesting three months together,” which I later learned was something called Seminary. He told his audience that meditation had been good for his composing, but then added that his mother might not agree with him on that. He immediately blushed after saying that, embarrassed that he’d revealed something so personal.

About 20 musicians attended his second talk, at my apartment. As I remember, they listened with interest but didn’t seem to know what to make of it. But I do remember one person saying that she liked him and liked his energy. Looking back, it seemed that in both talks he was doing his best to encourage people to practice meditation and that the whole Shambhala endeavor Rinpoche had asked him to help with was immense and very new. He handled his responsibility with dignity and grace.

At this second talk I also met his wife Ellen, who remembered me a few years later and was very kind to me. I can understand why Rinpoche chose the two of them to introduce Shambhala Training to people all over the country. They were clear examples of Shambhala elegance and humanity.

In the mid-1980’s, after I had moved to New York, Peter and I got to know each other a little as musicians. I attended a couple of talks he gave on music at Karme Choling and heard some of his compositions, and he heard some of my playing on tape and on video. Although we had very different personalities and backgrounds and I was a little intimidated by him, music was a language we had in common, and we were both devoted to spreading dharma through music. We were connected as musical vajra siblings.

I heard that before going to Seminary, Peter wrote music in an intellectually complex style, but that after Seminary he dropped this style and rediscovered the beauty and power in a simple melody. I admired him for that and also for boldly telling the public that his compositions were based on Tibetan Buddhist themes. He had a razor-sharp musical mind and the passion to go with it, and it meant a lot to me that he appreciated my work as a pianist and teacher. My playing had changed radically as a result of meditation practice and playing for RinpocheI had had the shocking experience of discovering a tremendously streamlined physical and musical approach that very few people understood, and I had just begun the long, difficult path of working to help other performers cut through habits to become more of an open channel for music. Peter was the only person I knew who knew what it meant to break through musical ego and let go of all familiar habits, and his understanding and encouragement helped me in a unique and profound way. It gave me strength on my path.

Many years later, Peter also kindly joined the Advisory Board of my fledgling nonprofit, Golden Key Music Institute, and even volunteered Lorraine for that position. Once again, I was grateful for his support.

Although I never knew Peter well and wouldn’t presume to understand him, I had the impression that as Lorraine rose to the peak of her career and as she battled cancer, he spent a lot of time and energy serving her. The experience seemed to really soften him, and his heart seemed to open up on a whole new level. His warriorship inspired me, and his music also became even more beautiful and inspired during that time.

It’s clear to me that Peter fulfilled his vow to Rinpoche to spread dharma through music. Beyond simply giving his compositions titles from the Shambhala Buddhist tradition, the music itself conveyed fearlessness and gentleness, power and glory. I particularly remember Ashoka’s Dream, with its penetrating power, and Neruda Songs, which I heard live in Lorraine’s performance with the Boston Symphony at Carnegie Hall. The writing was spectacularly beautiful, and it moved me to tears.

The one performance I attended of him as a conductor was the Brahms First Symphony, the night before the Sakyong Empowerment in Halifax in 1995. To this day, it remains the most exciting musical performance I have ever heard. As I wrote in the epilogue to my book, “This monumental work came to life with such clarity, directness, passion, and abandon that Brahms’ beating heart, in giant form, seemed to fill the hall. After the last note had sounded, the audience gave the performers a long standing ovation. Many people spoke about the performance as enthusiastically as I did. With all the music we had heard in our lives, we didn’t know that anything this sensational could occur. . . Mr. Lieberson took many bows after this performance. Toward the end of our ovation, he picked up the score from his music stand, held it up, and pointed to it as if to say, “It’s all in there. All we did was give you what he wrote.'” It was his devotion and lack of ego that gave him access to the immense power in the music.

When I sent Peter the whole epilogue for his feedback and approval before publication, I was surprised to hear him say that he “first had to get over the experience of being complimented.” I had mistakenly assumed that he knew how great he was and wasn’t vulnerable to anything I might say. As powerful as he was, he was human.

I was looking forward to interviewing Peter and Lorraine for my second bookabout meditation, confidence, and performancebut then Lorraine died, and he got lymphoma, and I didn’t want to bother him about the interview. I sent him a number of cards during his last years, as news arrived of the latest medical treatments he was undergoing. The last time I saw him was when he brought his lovely new wife, Rinchen Lhamo, to the New York Shambhala Center to see the Sakyong. He looked great, and I was happy to see him with her, radiating lungta and continuing to celebrate life.

Peter’s absence is luminous, just like his presence was, and I feel he will always be with me. I am deeply grateful for his kindness, brilliance, and devotion, and for the great music he gave to the world, filled with love, dharma, and enlightenment.

-Madeline

No postmortems, please

by Gregory Orr

No postmortems, please.

The world is immortal.

The world renews itself.

What about poems and songs —

Do they perish

Maybe they only

Vanish awhile.

Maybe they go underground

To gather some other

Knowledge and come back

In another form:

New words, a new melody,

Yet somehow

The same beloved,

Singing the same song.

~ Gregory Orr ~

***

Peter gave something very precious to this sangha: as Director of Shambhala Training International, he guided the Shambhala Training programs through a time of turmoil in our community, never allowing them to become politicized and keeping Shambhala Training’s integrity intact. I worked with him during this time and was so impressed by his steadiness in a difficult time.

Becky Hazell

***

For Peter Lieberson

To my old friend and colleague, Peter, with admiration,

I send one last farewell to you on your journey.

I knew Peter since the early days in Boston,

Where we grew up into the Dharma together,

Subsequently, we visited (and dined) in many places,

Including Halifax and Santa Fe,

And last year in Houston.

I can see you smiling then, sweetly as summer birdsong,

Although summer had long since passed.

You carried the banner of Shambhala in your person for many years.

Meeting Jetsun Khandro Rinpoche, you pursued your path practicing the Ati view.

I recall the premier of your first concerto by the Boston Symphony,

And seeing the great conductor Seichi Ozawa at your home.

You were friend and acquaintance with many such luminaries.

I remember when you pioneered directing Level III Shambhala Training in Boston.

I recall vividly the many times you and Ellen, your young family and the Boston sangha

Celebrated together our great mutual discovery.

You wore your cultural aristocracy precisely, easily, without pretense.

We plowed the ground of Boston together,

From Cambridge to Copley Square;

I recall you laughing uproariously at absurdities;

You could fly when the crazy winds blew.

You always did your work carefully and well,

And at the same time, you were a tiger cub playing,

Not stuck in the ways of the world:

Last time we met, you said Sam Bercholz remarked to you,

“Well, somebody has to buy retail!”–

And you laughed that laugh that burst the room.

I remember you proudly introducing me to Lorraine–

The diva for whom you said you served as “kusung,”

Who became the most admired mezzo soprano in America during those short years.

It is almost as you gave your life so that hers might reach its peak.

Meeting Rinchen last year with you in Houston

Was wonderful–you were genteel, hospitable, and it had become clear

That the heart of practice had taken your path,

A completion greatly to be yearned for.

Your passion for musical composition continued to the end

Since your genius had come into its own with the Neruda Songs.

You had much to give in this life, of that you had no doubt–and you gave it.

Of your many talents and generosities, this is the one that touched me the most:

You had the confidence and took the time to give your gifts.

With a full throat and wet-eyed memory,

My vajra brother, I acknowledge you, and your passing.

It has been a privilege to walk this path with you.

In the words of William Butler Yeats,

Inscribed on his own grave:

“Cast a cold eye on life, on death

Horsemen, pass by!”

Bill Karelis

April 25th 2011

***

Peter was my Meditation Instructor when I was a Shamatha student in Boston. I was part of the group of sangha members who went to Peter’s first concert with the Boston Symphony. We got to go backstage after the concert, which was very exciting for me. I decided to ask Peter to sign my copy of the program. Later when I got home, I opened the program and he had written: ‘To my darling Alan, keep sitting, love Peter.’

Alan Ness, Seattle

***

Peter was a student of mine at the NY Dharmadhatu in the mid 1970s. He had long hair and a bushy beard. One day an elegant cleanshaven prince showed up for class. I had no idea it was Peter. When I asked why he hid behind that beard for so long he told me he wanted to be seen for who he was, not what he looked like. We were best of friends, then more, and eventually were engaged, then finally friends again. He was elegant and romantic and silly beyond belief. Once in Santa Fe, he told his mother Brigitta that he had seen her old friend, Doctor Shoes ‘n’ Socks at the tennis court. She tried so hard to remember who he was. Peter was comfortable in all worlds: Tossing back Cuban-Chinese in a dive with Allen Ginsberg on the lower east side, or having tea at Claridges in London. He was of the earth and the heavens and I will love him always.

— Wendy (Ferraris) Tigerman

***

This little poem was inspired by Peter’s passing, but then I thought it really applies to all our dear sangha members. Please use as seems right to you.

Old friends’ passing rends

Life’s fabric, warp and weft unique.

Ah, how precious every thread

Joined by the thread sublime.

~ Connie Moffit

***

I met with Peter to talk about composing music between 1986 and 2001, studying intensively with him in the fall of 1995. Here are a few snapshots and paraphrases.

He once said to me, after I had been babbling something about emptiness: “Other teachers say ‘it’s all empty, it’s all empty.’ Trungpa Rinpoche said ‘It’s real. it’s real.’ We need to figure out what he meant by this.”

Peter’s music manuscript was both beautiful to look at, and incredibly precise. He was trained before computer notation, and used special soft pencils that he hand sharpened, the old fashioned way. It was calligraphy with a pencil. He used to admonish me because my sharps and flats would be in the vicinity of the note they modified, but not on precisely the right line or space. He would say over and over: “You have to be very definite. Everything you write has to be very definite.”

One of his favorite quotations (at least to me) from Trungpa Rinpoche: “You have to be willing to make a target out of yourself.”

Once I asked him if he ever did the practice of the stroke of Ashe before composing. He said “No, I just raise windhorse.”

Windhorse means different things to different people. It’s a big topic in our community. Here’s one way of describing it: an experience of brilliant and genuine reality, free from fixation, infused with the energy one needs to move forward in one’s life.

Peter was one of the best examples of the sad/joy of windhorse this sangha has ever known. Luckily for all of us, his windhorse is in his music.

Alexander deVaron

***

Though I did not know Peter well, I feel he revealed his genuine heart to me. I have not seen him for years, but the last time back stage at some performance event, we met as genuine human beings creating that moment of contact .

His passing touches an aching hole in my heart and marks an irretrievable loss for our suffering world. Pass on, oh good-hearted, elegant Peter.

Yours in the shared vision of Great Eastern Sun,

-Joan Whitacre

***

Jose, Bill, Eamon, Peter

I was just a gawky teenager at Naropa in ’74 surrounded by talented young grown-ups. Jose was crush material good looking, impressively into exotic Mayan stuff, whatever that was. Years later I went to Seminary with Bill and I think Eamon, too. More years elapsed. I was at RMDC/SMC during the Harmonic Convergence and Jose was on the radio and we sat around wondering if there could be anything to it or not. In time, I moved to Boston. Peter was a professor at Harvard and a famous composer and I was just a student there but nevertheless he was always so sweet and friendly to me. Time passed (as it is wont to do). I became conscious of my graying hair, bought stronger face creams. Death was still just a nasty rumor. Eamon became my landlord in Oakland and led a dathun at which I was an MI. I was hurt when he told me I squirmed too much on the umdze seat. I remembered Bill through his interesting intellectual emails on Sangha Talk. Eamon looked the part of the classic salty dog. He was so obviously tender when I spoke to him after Michelle’s death. Jose became a cult phenomena. Peter, another wildly handsome man, was long married to Ellen, then more life happened and I learned that he’d married a woman with the voice of an angel and then he married again after she died. Needless to say, the music lives on. Meanwhile, I’ve passed beyond middle aged and now death seems to loom everywhere.

Thank you to each of these brilliant men who have been such sparkling threads in the tapestry of my life in this mandala.

Barbara Handler

***

Three Gentlemen

Three gentlemen: now you see them,

now you don’t… left the action leaving

only traces; meetings with remarkable men.

We’ll all go this way…vanish into non-everything…

and when the door clicks behind us, the rest will

go on, forgetting once again it’s all a dream.

-John Tischer

***

Sam Bercholz on Peter’s passing

The entrance to the celestial pure land of Shambhala opened today, and the Vajra Warrior known on Earth as Peter Lieberson is welcomed back by the Rigdens, their Queens, and the general populace. The music that he had composed is playing in the Inner Kalapa Court.

Peter was a genuinely elegant man, a natural gentleman warrior of the Shambhala Kingdom. Throughout his life he exuded a friendliness and basic goodness to others and a wonderfully zany sense of humor. He was a musical genius, a loving father and husband, an accomplished teacher of the Shambhala dharma and Buddhadharma, an astute student of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Mindroling Jetsun Khandro Rinpoche.

When I think of Peter, a variety of memories come to mind. I remember how the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche encouraged his musical composing skills and asked him to make it a vehicle for the transmission of dharma, and he did do that, just as he had promised. He paid his dues by getting a Ph.D. from Brandeis University and then teaching musical composition at Harvard University. He wrote several Tibetan Buddhist-inspired operas, working with his friend Douglas Penick, and wonderful music that expressed the teaching of Buddhism; his Six Realms is playing in the background as this is being written. He also wrote sublime love music in the form of his Neruda Songs and Rilke Songs that he composed for his second wife, the mezzo-soprano, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. All the important American orchestras and many European ones play his music, and he collaborated with many great musicians including the pianists Peter Serkin and Emanual Ax, and the cellist, Yo-Yo Ma. I once asked Peter how he wrote his music, at that time he replied: I make an offering and then simply write down what I hearâ?.

He was born to artistic royalty, so to speak, his father was Goddard Lieberson, also a classical composer and then longtime head of Columbia Records and his mother was the ballerina Vera Zorina (she had been previously married to George Balanchine). Though he was brought up on jazz and classical music, he was no cultural snob. He appreciated and was a fan of the pop-singer Sting and of the antics of the comedian Pee Wee Herman. He really enjoyed watching Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and he would always laugh uproariously.

When Trungpa Rinpoche started Shambhala Training, he appointed Peter and his wife Ellen Kearny Lieberson to become the spokespeople to the public. Peter was also one of the first Shambhala Training teachers. Later in his life he became the international director of Shambhala Training in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Though he was no bureaucrat, he handled his assignment with great diligence and dignity.

He truly understood and believed in Trungpa Rinpoche and served as an outstanding student, example for others, and an excellent administrator during Trungpa Rinpoche’s lifetime and thereafter. He also was very interested in learning further about the Nyingma Dzogchen teachings. I remember his fascination with the terms trekcho and thogyal. He really wanted to find a teacher that would fill-in this aspect of Buddhism for him. He met the Nyingma master Mindroling Jetsun Khandro Rinpoche and was able to fulfill this wish. After a few years, she appointed him as one of her community’s senior teachers with the Tibetan title Loppon (Master in English).

Peter had lymphoma, a form of cancer, for the last five years. I was impressed by the way he handled the difficulties of his illness with such aplomb. He rarely complained and continued to write music and practice and teach dharma. He spent his last years with his long-time friend, companion and wife, Rinchen Lhamo, who survives him.

Peter Lieberson was the living embodiment of the true Vajrayana Buddhist practitioner and Shambhala Master Warrior. He was able to be fully in the world and at the same time practice the profound inner view of luminosity and emptiness.

—–Sam Bercholz, April 24, 2011

***

Peter Lieberson – – –

He tapped a rhythm

on my skull

on my skull

bonehead tiger, lion, garuda, dragon

bonehead tiger, lion, garuda, dragon

Mr. Lieberson taught Shambhala Culture at my seminary and was my meditation instructor (1981). He determined that I should be sent to bonehead Hinayana, for which I am eternally grateful. As a classically trained trumpet player, I stood in awe of his insight into music and how his presence was evocative of that single tone that can be an expression of joining heaven and earth.

In loving memory,

Darryl Burnham

***

Not enough is said in the tributes about his contributions to Shambhala Training. He and his first wife were sent to Boston by the Dorje Dradul to start the first Shambhala Training programs, at a time when everyone was still just a Buddhist. He became the Director of Shambhala Training in Boston for many years, and then, in Halifax I believe, became the International Director of Shambhala Training for several years. So he was also a prominent teacher in our sangha.

Ellen Berger

***

From the New York Times, September 29, 2009

By Allan Kozinn

When Peter Lieberson began composing in the early 1970s, his compositional hero was Stravinsky in his late acerbic style, and his teachers included Milton Babbitt and Charles Wuorinen. But he was also fond of musical theater, Minimalism and jazz; before he studied composition formally, he learned about harmony by figuring out the voicings on recordings by the jazz pianist Bill Evans. Mr. Lieberson’s works meld most of those influences into a cohesive, energetic and intensely communicative style, with brainy, atonal surfaces that attest to his post-tonal pedigree and a current of lyricism and drama that gives this music its warmth and passion.

***

I remember several years ago many of us who were then in the Los Angeles Ashe Society went en masse to hear Esa-Pekka Salonen conduct one of Peter’s orchestral works, perhaps it was Drala. And later, in 2005 my wife and I were fortunate to hear the world premiere of Neruda Songs with the same great orchestra and conductor, as well as hear the transcendent voice of his wife Lorraine. I was always so excited that there was an emissary of enlightened society in the world of classical music – as a musician and Shambhalian that always gave me hope. And that he was so highly regarded as well……

The world has lost not just a great voice in his wife Lorraine but now a great voice in modern classical music. May all of us in the arts aspire to be able to bring such sanity to the world as Peter and his music did. And may he be smiling in the bardo to the painfully beautiful and out of tune voice of the Dorje Dradul singing the Shambhala Anthem. Thanks for the music Mr. Lieberson.

Joel Wachbrit

***

Links

NY Times: Peter Lieberson, Composer Inspired by Buddhism, Dies at 64

Elephant: That foreign yet visceral language we call music.