Bill Gilkerson died in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia on November 29, 2015 after an eight-year illness. A great-hearted man of high talent, he was a deeply loyal student of the Vidyadhara.

Bill was born of Scottish forebears in Chicago, Illinois, in July 1936 and raised by his adoptive parents in Wisconsin. His adventures began when, at the age of 14 he left his Clayton, Missouri school and set out into the world at a run, signing on as mess boy aboard a Norwegian freighter bound for Ecuador; by 16 he was on his own in Paris, “allegedly” studying art on his mother’s support at the Academie Julian; by 17 he’d joined the US Marine Corps and earned a stripe and the Expert Rifleman decoration; after his honorable discharge he attended Washington University’s Bixby School of Fine Arts, then earned a living as a nightclub sketch artist and freelance illustrator in St. Louis; from there he headed to Norway, where he bought himself an antique sailing sloop and sailed around Northern Europe.

Swept on by his personal wind, he found his way to the U.S. West Coast, where he became an editor and then special features writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, living aboard a new boat, a 38′ ketch. As features writer he was asked to do a piece on Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet during their pioneering visit to San Francisco, then swung that into the job of hosting the entire corps. His own yacht being too small, he borrowed a friend’s, and proceeded to carry the evening off with panache, apparently winning over the ballerinas in the process.

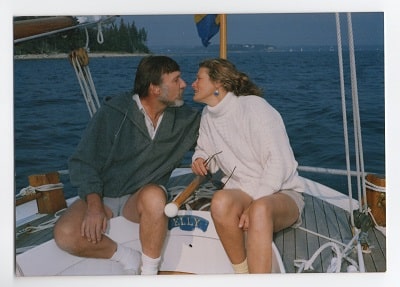

Tacking again, in his mid-thirties he jettisoned his newspaper career and joined a group of street buskers named The Golden Toad as their bagpiper, living hand to mouth. A while later he met and fell in love with Kerstin Helleberg, whose Swedish singing he heard as “a burst of birdsong unto the world.” They were married in 1978. His swashbuckling days now over, he turned to crafting “a career, any career that would again provide a viable livelihood.”

Gathering his various passions together, Bill began to work as a marine artist and scrimshander, which took the newly-marrieds from California to Massachusetts. Shortly afterwards, we met at the Boston Dharmadhatu, and soon after that Bill gave me an old army tenor drum and recruited me into their busking group – Kerstin attired in a lovely Swedish folk outfit, Bill dressed as an 18th century French bagpiper, me as some sort of kilted Scot. We played on Saturday mornings at Boston’s old Faneuil Hall and, thanks to some city contract Bill arranged, made a surprising haul.

A few months later Bill and I played for Trungpa Rinpoche when he came to town. Being winter, it was indoors, and the instruments were preposterously loud, but Rinpoche seemed delighted. Later, at Rinpoche’s request, we played in the dining room at BPB, Karme Choling. The command performance turned out to be in honour of a visiting lama. Trapped in the small, bare-walled room, amidst the wail and screech of the pipes and the thunder of the drum, the hapless guest may have felt that he was undergoing a form of CIA torture – anyway, his eyes grew gradually wider, finally taking on the look of a cornered prey. Rinpoche, meanwhile, became more and more animated as the cacophony roared on, waving his swagger stick in sweeps around the room, his eyes taking on an ever wilder, more joyous gleam. Years later, of course, we learned that he wasn’t that partial to bagpipes.

As Bill built his career from the late ’70s on, he interspersed writing and painting. By the end he’d authored and illustrated 13 books, two of which became the standard references in their fields: his two-volume treatise on the development of ships’ weapons, Boarders Away I & II, and a book on John Paul Jones’s flagship BonneHomme Richard. At one point some of his artwork hung in the White House, and it has been commissioned and collected by some 50 institutions and museums, among them the National Geographic Society; Museum Of Fine Arts, Boston; Archéologie Navale Francaise; Massachusetts Institute Of Technology, National Library of Congress; National Library of Scotland; U.S. Naval Academy Museum; and the U.S. Naval War College.

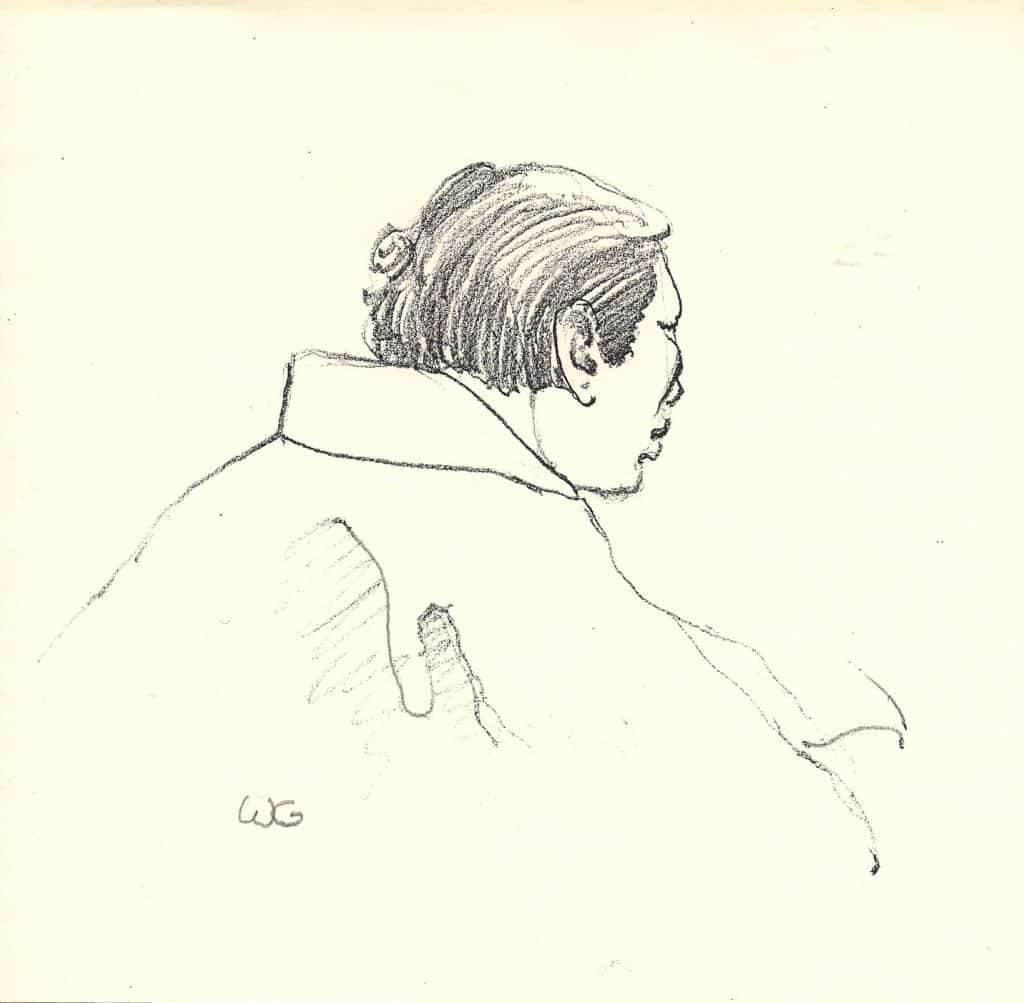

From where he’d begun, in his forties, these were towering achievements. But the best was yet to come. Bill once said “I’ve been lucky in my teachers,” and he devoted his last years to “trying to adequately portray my primary mentor, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who remains a challenge.” In at least one sphere, he seems to have succeeded: a pencil drawing he did of the Vidyadhara was described by Rinpoche as the best likeness of him he’d ever seen.

In 1998 Bill published his first novel, Ultimate Voyage: A Book of Five Mariners, a maritime historical yarn in allegory form. It was an ambitious work: the five boy mariners, all born on the same day during the Renaissance in the same port town, each represent one of the five Buddha families, and together they embark on an uncharted and occasionally harrowing voyage of spiritual discovery.

In 2006 Bill was diagnosed with myelodysplasia, a rare blood and marrow disease, and given six months to two years to live. But he had work to do.

Read Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in Quick Charcoal, Bill’s account of drawing Trungpa Rinpoche.

by William Gilkerson

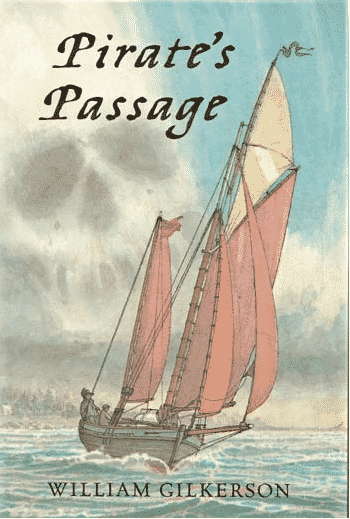

The following year he published what he felt was his magnum opus, Pirate’s Passage. In the novel he took a more direct approach to portraying his teacher. An eccentric seaman named Captain Charles Johnson arrives in his boat in a minor seaport in Nova Scotia; he then takes up residence at an inn run by a boy and his mother who are under threat from a rapacious businessman going after the inn, their birthright. The captain takes the family under his wing, teaches the boy valuable life lessons, and helps the family to outmaneuver and eventually defeat their oppressor. In spite of his warmth and vivid humanity, there is something mysterious about the Captain: how can he know in such detail the day-to-day experience of sailing on a pirate ship, or of growing up among Vikings or about the loves of Grace O’Malley, the pirate queen of Ireland?

In spite of its benignly subversive intent, the book has been an unambigous triumph, winning the Canadian Governor General’s Literary Award, the citation describing it as “a work of genius … a challenging children’s novel with a dangerous edge … a benchmark in Canadian literature.” The actor Donald Sutherland based his animated adventure film Pirate’s Passage on the book. Just a few days before Bill’s death, the film was bought by Netflix; at the time of his death he was working on its sequel, which would have been his 14th book.

Walking into the Gilkerson home was to step into the adventurous, fire-lit world of the late-18th century. In the entrance hall was a marble bust of John Paul Jones, an American naval hero of the Revolutionary War; on the coat rack hung a tricorn hat and a thick weather cloak of sort highwaymen wore; in Bill’s study were swords, flintlock pistols and blunderbusses and soaring shelves of books, some of them very old, on ships and men and pirates; one of the treasures was an authentic Spanish doubloon retrieved from the wreck of the legendary Blackbeard’s ship. In the living room, next to a blazing log fire, Bill celebrated his many passions with his guests, people with a love of ships and sailing, of sailors and their weapons, of sparkling conversation and fine food. There he would often draw on his remarkable literary memory to transfix guests by reciting long passages from “The Canterbury Tales,” the Olde English redolent of campfires and human closeness.

Those evenings, Bill’s star shone bright. Yet most were aware that its luminosity was not all his: in more reflective moments he allowed that the art and literature to which he owed his stature owed everything to Kerstin – that it had been his determination to support the woman he loved that impelled him to give up a buccaneering lifestyle and to craft a career. And it was Kerstin who year after year conjured up the warm and gracious space, the glowing food and hospitality, in which all our stars could shine. Theirs was a full and fruitful union, the gifts the rest of us partook of theirs together; and if there was ever an enlightened kingdom in the Province of Nova Scotia, this felt like one of its shining outposts.

There was an overflow crowd at his Sukhavati, a mix of local people, and those from as far away as California. The Gilkerson children, Anna and Jack, made moving, heart-felt speeches; Ellen Kearney sang a lovely Irish song; Crane Stookey – the founder of the Nova Scotia Sea School – gave a stirring eulogy. He talked of Bill’s profound sense of space and detail, and how they manifested in his life, work and sailing. His studio joined a “super-ratna richness and meticulous attention to detail, that somehow induced a feeling of simple comfort, a space that, as soon as I entered it, let me feel relaxed.” Crane saw it in Bill’s painting too, how, “even in crowd scenes the sky is a major element … You’re fascinated by the level of detail and expanded by the use of space, all at once.” Bill also communicated it in sailing, in his delight in meticulous attention to details and their exact placement, all out in the most spacious environment on earth: then, in his boat Elly, gurgling resonantly as she moved through the water, it was in the “display of flag and sail aloft that small and vast came together.” There, Crane said, he began to understand meditation in action, vast mind and ordinary day together – an insight that became the core idea behind the Sea School project.

In Bill’s last days, in Bridgewater Hospital, he bore himself in illness as he had in life, with bravery and gallantry, and with an open enjoyment of his world and those he met. Nurses loved him, as he did them; charming and still gently swashbuckling, he complimented them on their beauty and the quality of their care for him, and when they arrived on shift and asked him how he was feeling, he would invariably say: “All the better for seeing you.” For those who’d known him, the feeling was entirely mutual.

-GM

Stefan Carmien writes:

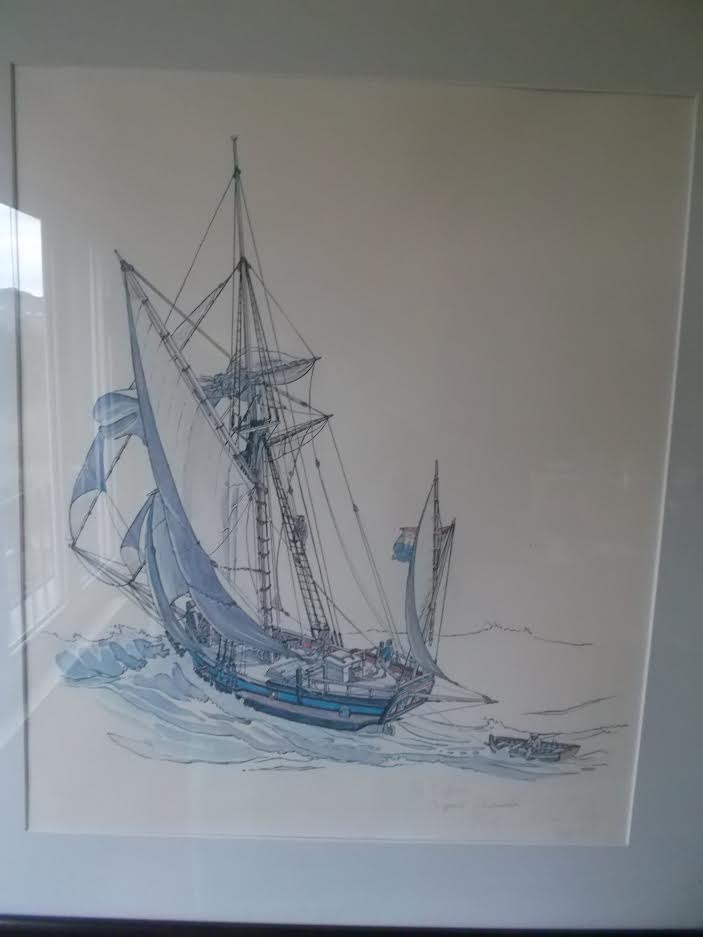

Bill gave me the painting you see to the right at a Purnachandra gatehring at his home in Mass. [The Phunachandra was the naval arm of the kasung.] The story was that he and the Vajra Regent worked up the sailors and their attributes [each sailor represents one of the buddha families]. Later I wrote to get the families correct and Kerstin sent me the this.

The gentleman on the tiller represents Vajra, the one in the little boat bailing, Buddha, the one on the quarter deck leaning on the rail, Ratna, the one half way up the rigging in red is Padma, and last but not least Karma furling a sail. Their names: Pilot, Crew, Stewart, Flags and Bosun. Cheers, Kerstin

This is hanging in my living room in Hernani Spain. If you look carefully it has a cool inscription to me.

Love,

Stefan

***

Terry Kilshaw write:

I knew met Bill and Kerstin when we lived in Nova Scotia. They were just as as GM describes then so eloquently in his tribute. We sailed together and shared some memorable times.

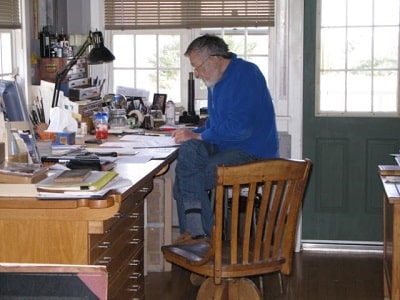

I recall one time sitting in Bill’s studio talking about this and that while Bill just doodled on a sheet of paper. But the doodle transformed, seemingly without effort, into a seascape with a ship under sail, with great detail. It was like watching a photographic print develop.

Another time John Perks, who was running a school for butlers in Halifax, provided a trainee butler who served us all dinner in great style, after which John and Bill dressed me in strange plaid in the Macbeth tartan with odd Velcro attachments and a huge blowsy white cotton shirt. Then Bill played us a pibroch on the pipes. It seems that that sort of thing tended to just happen around Bill.

Truly one of a kind.

My heart goes out to Kerstin and their children.

***

The Strange Event at Owls Crossing

It is with some trepidation that I take up my pen to write this tale, this story, this happening. Because as I go over the circumstances, the whole thing seems like a dream except for two solid items that now sit on my desk as I write—the sword and a broken, yellow, ancient scrimshaw cow-horn beaker inscribed with the name, “Billy Bones, His Cup, 1690.”

It was in the last days of 2015, late at night, stormy at that, that I made my way by car up from Mahone Bay, Martins River, to be exact, where I had attended a memorial service for William Gilkerson. My hostess had offered to put me up for the night. “There’s a storm coming,” she said.

I looked out at the darkening sky, “Oh, I can make it to Halifax before it hits,” I said. “But thanks. I have a meeting in the early morning.” So off I set.

I had planned to take the highway north a few miles above Martins River and had turned right up the Coast Road. Within less than a mile the storm hit. A complete white out, freezing rain and snow. I crawled along at five miles an hour wishing I had stayed at the warm house in Martins River. Muttering to myself in desperation at my situation, “Darn, I can’t see a bloody thing.” But thinking somewhere ahead there must be the turn off for the highway.

The car shook with the gale, the windshield wipers strained to keep up with the piling snow and ice. I had the defroster on full blast but all I had to look through was about ten to eight inches of clear glass. And that was closing up fast. Yellow lights flashed ahead. “Thank, God,” I said to myself. A figure appeared between the lights in a yellow slicker. He banged on my side window as I pulled up. I tried to roll down the window but it was frozen shut, so I opened the door.

“Where be you going, sir?” he asked.

“Halifax,” I yell.

“Oh, you’ll not be getting there tonight,” he replies. “All the roads are closed.”

“Well, what should I do?” I asked, in a somewhat plaintive voice.

“Well you’re in luck, sir. About 20 yards up is the road to Owls Crossing.”

“What’s there?” I shout.

“The Inn,” he says. “They’ll put you up.”

“The Inn,” I replied. “What Inn?” I had never heard of Owls Crossing.

“Why, sir,” he shouts back. “The Golden Hind! Just 20 yards, turn right at the sign for Owls Crossing.”

It was then that I noticed he was wearing an oil skin fisherman’s storm coat and a tricorn hat. I had first taken him for an officer in the R.C.M.P. Before I could inquire more, he had disappeared into the whirling white soup.

I moved the car at a snail’s pace up the middle of the road. Then in the headlights, sure enough, a sign on the right appeared with an arrow and “Owls Crossing – 1 mile.”

In the white out, the one mile seemed more like ten. The car crept along in what appeared to be the middle of the road. Eventually, dim lights appeared on the right side in the near distance. And I saw a swinging sign above a dark building that read, “The Golden Hind Inn.” There appeared to be candles in all the windows. I pulled up or rather slid up in front of the entrance. Before getting out of the car, I reached into the back seat and picked up the sword, making sure I didn’t lose it. Then out into the cold whipping wind, I approached the massive front door.

I swung open the door and was overwhelmed by the noise, smoke, and the throng within. It appeared everyone was in some type of costume—seamen, sailors, pirates, fishermen—all jammed together. The smoke from pipes and cigars filled the air, along with the smell of sweat, oilskins, sea water, and rum. My immediate thought was, this must be a reenactment party of some kind that I had blundered into. I pushed my way through the crowd to the bar, which seemed to be made of planks laid out on top of lobster pots.

The tall, thin bartender said before I could ask, “What’ll it be matey?”

“Scotch and soda,” I said above the din.

“We don’t have none of that here. It’s rum or grog. Which’ll it be?”

“I’ll take grog,” I said.

“You want it hot or cold?” he replied.

“Hot will be fine,” I said.

The man passed me a steaming porcelain mug of what seemed to be hot buttered rum. Then he said, holding out his hand, “John Silver’s me’ name.” Before I could reply he continued, “How are you doing tonight, Auntie?”

I was somewhat taken aback. Then with my hand still clutched in his, he pulled me halfway across the bar and said, “Auntie Granty, that’s right, ain’t it?”

“How did you know that?” I asked, astounded.

“Everyone knows that in these parts, matey,” he said.

Before I could reply he passed another mug of steaming grog across the bar, saying “Here, do me a favor, take this over to the Captain, sittin’ next to the fire. Captain Johnson, that’ll be him. He’ll tell you the lay of the land.”

Tucking the sword under my arm, I grabbed the two mugs and headed for the fireplace, where a dark figure in a boat cloak was sitting smoking a pipe. As I approached, the man turned and looked up at me. “Auntie, he says, we was expecting you.”

Again, I was stunned at the unaccustomed familiarity. Taking from me a mug of grog with his left hand, he held out his right hand, which was as big as a dinner plate, and said, “Captain Charles Johnson at your service. Set ye down here,” as he motioned to a chair. “Perhaps you have questions.”

I laughed, somewhat nervously, and asked, “Is this some type of reenactment group party?”

“Taint no reenactment, Auntie,” says he. “This be the real thing. For one thing, Billy named you right. ‘Auntie.’ Never take anything at face value. That be you.”

Before I could reply, he said, “What are you doing with John Paul’s sword there?”

“That’s not John Paul’s sword,” I said, correcting him. “Major Perks gave that to Bill Gilkerson.

At that the Captain burst out laughing. “Them’s just cover-up names,” he said. “Perks, he be Black Dog and Gilkerson’s real name is Billy Bones. Both of them sailed along with Admiral Diamond. Him a pirate too. Came out of Tibet with a Mauser machine-gun pistol stuck in his sash and a Tibetan dagger at his side. And that sword in your hand be the sword of John Paul Jones, another cover-up name, because Billy Bones, he were literally the flesh and bones of John Paul Jones.

I was too amazed at all of this to even offer a reply. He looked at me with his piercing eyes locked on mine.

“Do you get it now, Granty,” he asks?

I took a long swig of the hot grog. It was slightly burning my mouth but easing my mind. “Where’s Bill,” about to say Gilkerson, but caught myself and changed it to, “Where’s Billy Bones now?”

“Well I’ll be meetin’ him quite soon. He’s provisioning our ship, the Merry Adventure down at the government wharf. We be sailing on the tide, going to the land where corals lie. You know the song, don’t you, Auntie?” he said?

Before I could answer he sang in a soft voice:

The deeps have music soft and low

When winds awake the airy spry,

When winds awake the airy spry,

It lures me, lures me on to go

And see the land where corals lie.

And see the land where corals lie.

At this point I decided that I must be dreaming and that the car had slid off the road and I had banged my head on the dashboard. I raised the grog and drained the mug and fell into a swoon right there in the chair as the crowd broke out singing, My father was the keeper of the Eddystone Light. He married a mermaid one fine night . . .

The next thing I remember is waking in bright sunlight, sitting in my car, by the side of the road. There was not a sign of any snow at all. And certainly no sign of the Inn or Owl’s Crossing. There was a tapping on the car door window. I looked up and a seemingly genuine R.C.M.P. officer was standing outside.

I rolled down the window and he asked, with some concern, “Are you alright sir?” We passed your car several times and you seemed to be sleeping.

Struggling to make a sentence, I replied, “Yes, I think I’m fine. Thank you, officer.”

I made the journey to Halifax contemplating these many astounding events and turned on the radio, where a soprano sang:

The deeps have music soft and low

When winds awake at the airy spry,

It lures me, lures me on to go

And see the land where corals lie.

By mount and steed, by lawn and rill,

When night is deep, and moon is high,

That music seeks and finds me still,

And tells me where the corals lie.

Yes, press my eyelids close, ’tis well,

But far the rapid fancies fly

To rolling worlds of wave and shell,

And all the lands where corals lie.

Thy lips are like a sunset glow,

Thy smile is like a morning sky,

Yet leave me, leave me, let me go

and see the land where corals lie.

Tears welled up in my eyes and ran down my cheeks.

Getting home, I picked up the sword laying on the back seat and noticed next to it a small brown paper parcel wrapped in tarred marlin string with the name, “Auntie Granty,” written on it. In my study I opened the package and there was an ancient cracked yellow cow-horn beaker, with scrimshaw of ships, sailors, and mermaids and the words, “Billy Bones, His Cup, 1690.” With it was a small note on parchment paper that read, “Welcome to the brotherhood, Auntie. When you gave Billy Bones the kiss, that was your initiation. Now that you have fallen through into another reality, cheerfully enjoy!” P.S. This is just to inform you that Billy Bones learned his craft as a balloonist. Ha ha ha ha. That be true.”

It was signed Captain Charles Johnson.

___________________________________

***

Please send tributes, recollections, and photos of Bill to ]]>.