Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche on Gene Smith

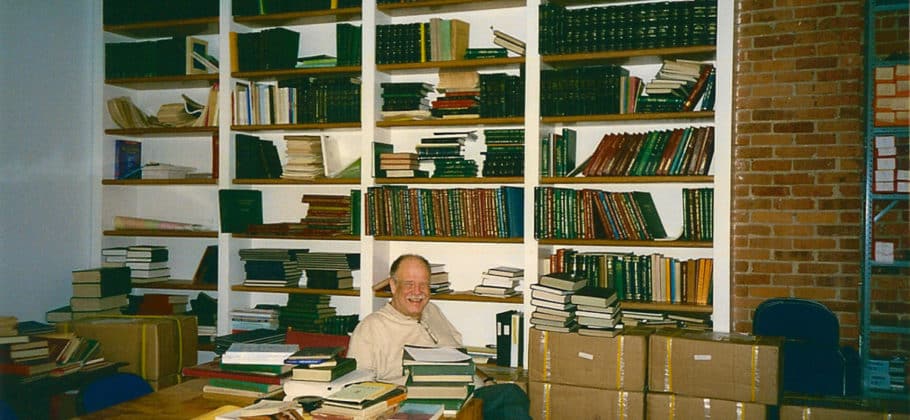

Smith did most of his seminal work of collecting, classifying and disseminating Tibetan books while serving as field director in India and later, Malaysia and Egypt — for the Library of Congress. He was, indeed, the peerless librarian, gatherer, savior and preserver, of Tibetan literature.

At the memorial, the scholars spoke, friends spoke and family spoke, remembering Gene’s immense generosity and geniality. The house in Delhi where he based his Tibetan literature work was a central gathering place for two generations of Tibetan translators, whom he would help in any way he could, always. A friend there who worked in his house recalled the parties Gene would casually assign him to prepare: a dinner for a few friends, mentioned casually early in the week, would in fact mean 500 guests were due to arrive within days.

Smith wasted no time in his life. He pursued his passion of Tibetan literature, with single-minded energy. He was up at 3 every morning, answering letters from scholars with questions for him and he was the go-to person for any scholar with an interest in Tibetan Buddhism. In Words of My Perfect Teacher, there is a story about Patrul Rinpoche’s boredom with ordinary conversation and alert interest whenever the dharma was discussed. Gene Smith was not like that he talked with animation about plenty of regular, worldly subjects. But when he was with a fellow scholar, talking about the provenance and content and lore of Tibetan books, he seemed fully and profoundly engaged and utterly authoritative though no layperson could possibly hold onto the gist of the conversation.

His extraordinary intellect was evident when he was a child, said his sister. As a small boy during World War II, he followed the movements of the Allied Forces by putting pins in a map on his bedroom wall. He went to the University of Washington to study East Asian languages, where he met Dezhung Rinpoche, probably the first Tibetan lama to teach in the U.S., a man of brilliant intellect and, as Gene said later, the most rational person he’d ever met. In the early 1960’s, when Gene was studying, there were, at most, a scant handful of Tibetan texts in the West. Eventually, Smith went to India to search for some, where he encountered the first waves of Tibetan refugees who fleeing the invading Chinese, escaping into India. Tibetans treasure their literature. In fact, as one speaker said, they have produced more writings, more books per capita, than any other civilization in history. Many had crossed the Himalayas with whatever books they could carry, carting them in water-logged packs or on the backs of yaks. Fortuitously for the dharma to put it mildly Congress had recently passed a law permitting India to repay some funds owed to the U.S. with books. Through the law, Smith, who was by then working for the Library of Congress, was able to pay the owners of Tibetan books, copy them, return the originals and distribute the copies to universities in the U.S. These books formed the first collections of Tibetan literature ever in the West, enabling students and scholars to begin the serious study of Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan history, autobiography, medicine, art and culture. In the process, Smith became a human library of their contents, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the teachings, lineages, biographies, categories, and provenances a subject as intricate and profound as any that has ever existed.

Smith loved good food. He loved spending time with friends. He loved having dinner with friends and usually insisted on paying. He was intensely modest. He was a brilliant linguist and scholar who was fully focused on helping scholars, translators and lamas carry on the work of studying, teaching and spreading the dharma for now and for countless future generations. As many of the speakers said, one after another, Gene Smith was irreplaceable. He was a giant and his work will certainly continue to resound for centuries, for millennia.

Barbara Stewart on the memorial service

St. John the Divine, a gothic cathedral on New York’s Upper West Side, has a sweep and grandeur that suited the memorial of E. Gene Smith precisely. Gene Smith, who died on December 16, had a humble grandeur, too, and the sweep of his life’s work with Tibetan Buddhist books could far outlast even the most solid stone cathedral.

On Saturday afternoon, Feb. 12, St. John’s was filled with Gene Smith’s friends, admirers, and fellow Tibetan scholars, translators and practitioners, sitting elbow-to-elbow on folding chairs, encased in heavy coats against the raw cold that penetrated the soaring but barely heated space. Some had come from Europe and Canada and India to honor the man who had rescued, copied and distributed tens of thousands of Tibetan books, creating the foundation of Tibetan Buddhist Studies in the West. Smith’s final years were taken up with the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, a project with offices in downtown New York that is currently in the process of digitizing his enormous collection of books well over 12,000, most consisting of many hundreds of pages. To date, 7 million pages of pecha oblong loose-leaf Tibetan books—often hundreds of years old—have been scanned. Scanning the books onto a computer hard drive and making them freely available ensures that the books —the heart, the treasure, of more than two millennia of Tibetan Buddhist teachings and Tibetan history, literature, medicine and biography—will be forever safe and forever open to all.

Links

Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center

E. Gene Smith Blog

New York Times

The Economist