This is Talk Six from Chogyam Trungpa’s Sadhana of Mahamudra seminar, November 30, 1975. This talk can be found in the Sadhana of Mahamudra Sourcebook. © 2002 by Diana J. Mukpo. Used here by arrangement with Lady Diana and the Shambhala Office of Media and Communications.

In 1975, Rinpoche presented two seminars on the Sadhana of Mahamudra. These talks are available in DEVOTION AND CRAZY WISDOM from Kalapa Media.

SEEMINGLY THIS is the last day of our seminar. The subject that we have gone through is connected with our general attitude to the sadhana principle. We have stayed somewhat on the safe side: the sadhana can be discussed at a much deeper level, but I feel hesitation to get into unnecessary problems. If people don’t have enough understanding of these.

This sadhana has been written in a traditional style. Sadhanas are traditionally written in a certain environment by someone who has a feeling about the subject. To make a long story short, there was tremendous corruption, confusion, lack of faith, and lack of practice in Tibet. Many teachers and spiritual leaders worked very hard to try to rectify that problem. But most of their efforts led only to failure, except for a few dedicated students who could relate with some real sense of practice. The degeneration of Buddhism in Tibet was connected with that lack of practice: performing rituals became people’s main occupation. Even if they were doing practice, they thought constantly about protocol. It was like one of us thinking, “Which clothes should I wear today? What shirt should I wear today? What kind of makeup should I wear today? Which tie should I wear today?” Tibetans would think, “What kind of ceremony can I perform today? What would be appropriate?” They never thought about what was actually needed in a given situation.

Jamgön Kongtrül, my root guru, my personal teacher, was constantly talking about that problem. He wasn’t happy about the way things were going. He wasn’t very inspired to work on a larger scale because he felt that unless he could create a nucleus of students who practiced intensely and who could work together, unless he could create such a dynamic situation he couldn’t get his message to the rest of the people. You might think that Tibet was the only place in the world where spirituality was practiced quite freely, but that’s not the case. We had our own difficulties in keeping up properly with tradition. Before the 1950’s, a lot of gorgeous temples were built, a lot of fantastic decorations were done. There was lots of brocade, lots of ceremony, statues, lots of chötens, lots of horses, lots of mules. The cooking was fantastic, but there was not much learning, not much sitting. That became a problem.

The degeneration of Buddhism in Tibet was connected with that lack of practice: performing rituals became people’s main occupation.

Sometimes Jamgön Kongtrül got very pissed off. He would lose his temper without any reason, and we thought that he was mad over our misbehaving. But he was angry over something much greater than that. It was terrible what was going on in our country. Many other teachers besides Jamgön Kongtrül began to talk about that: the whole environment was beginning to flip into a lower level of spirituality. The only thing we needed was for American tourists to come along. [Laughter] Fortunately, thanks to Chairman Mao Tse-tung [laughter], that didn’t happen, which actually saved us.

There are a few readings connected with that situation in the first part of the sadhana, which is about why the sadhana was written.

David Rome Reads:

This is the darkest hour of the dark ages. Disease, famine and warfare are raging like the fierce north wind. The Buddha’s teaching has waned in strength. The various schools of the sangha are fighting amongst themselves with sectarian bitterness; and although the Buddha’s teaching was perfectly expounded and there have been many reliable teachings since then from other great gurus, yet they pursue intellectual speculations. The sacred mantra has strayed into Bön and the yogis of tantra are losing the insight of meditation. They spend their whole time going through villages and performing little ceremonies for material gain.

On the whole, no one acts according to the highest code of discipline, meditation and wisdom. The jewel-like teaching of insight is fading day by day. The Buddha’s teaching is used merely for political purposes and to draw people together socially. As a result, the blessings of spiritual energy are being lost. Even those with great devotion are beginning to lose heart. If the buddhas of the three times and the great teachers were to comment, they would surely express their disappointment. So to enable individuals to ask for their help and to renew spiritual strength, I have written this Sadhana of Mahamudra.

VIDYADHARA: There were a lot of problems, obviously. Tibetan Buddhism was turning out to be a dying culture, a dying discipline, a dying wisdom-except for a few of us, I can quite proudly say, who managed to feed the burning lamp with the few remaining drops of oil. Suddenly there was an invasion from the insect-eater barbarians called the Chinese. They presented their doctrine called Communism, and they tried to use a word similar to “sangha” in order to hold together some kind of communal living situation, in order to raise the morale of the masses. But what they had in mind turned out to be not quite the same as the concept of sangha. So there was no practice, no discipline, and no spirituality. When the Communists finally realized that they couldn’t actually indoctrinate anybody, they decided to use greater pressure. They invaded the monasteries and arrested their spiritual and political leaders. They put those leaders in prison. Asking the Communists to do something about it further intensified their antagonism: rather than letting these political and spiritual leaders come out, they just told the stories of what happened to these prisoners. That created further problems.

I don’t want to make this a political pep talk as such, but you would be very interested to know that in the history of Communism, Tibet was the first place where workers have rebelled against the regime. The Tibetan peasants were not all that aggravated or pissed off by their situation before the Communists; they were well off in their own way. They had lots of space for farming. Maybe they were hard up in terms of comfort and things like that, but our people are very tough. They can handle the hard winters; they appreciate the snow and the rain. They appreciate simple ways of traveling; they don’t need helicopters or motorcars to journey back and forth with. They are very strong and sturdy; they have huge lungs in order to breathe at a high altitude. We’re tough people! The peasants took pride in those things, obviously. Their faith and their security and their pride was based on some kind of trust in the teachings and in the church, which was slightly crumbling but which still remained. So for about nine months new energy was kindled, and the peasants rose up against the Communists. That was the first time in the history of Communism that such a thing took place.

After I was forced to leave my country, people from my monastery sent me a message: “Come back. We would like to establish an underground monastery.” I wrote to them, saying, “Give up. It would be suicidal. I’m going to leave India in order to do my work elsewhere.” So that was that. Hopefully they received my message; hopefully they left my country.

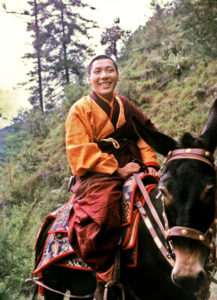

My journey out of Tibet, my walk across the country is described in Born in Tibet. I appreciated enormously the beauty of that country, although we saw only mountain range after mountain range after mountain range. We could not go down to the villages because there might be Communist spies there to capture anybody who was trying to escape. So we saw fantastic mountain ranges in the middle of winter, fantastic lakes on top of plateaus. There was a good deal of snow, and it was biting cold, which was very refreshing-fantastic!

I finally crossed the border into India, and took my first plane trip-in a cargo plane provided for us by the Indian army. I was excited to fly for the first time, and it was a good trip. A lot of my colleagues got sick; a few were very nauseated. But I was very interested in getting to a new world. We arrived in the refugee camp, where I spent about three months. I could talk on and on about that life, which was very interesting to me because I was having a chance to explore what it was like outside of our world.

India was very exciting to me: in Tibet we had read all about India in our books. We studied all about it, particularly about the Brahmins and the cotton cloth that they wrap around themselves. We talked about Brahministic ceremonies, and all kinds of things. It was very interesting that finally history was coming to life for me. It was good to be in India, fantastic to be in India.

Then one day I was invited to go to Europe, and I managed to do so. I traveled by ship, on what is called the Oriental Lines, or something like that. It was interesting to be with people who were mostly Occidentals. They had a fancy dancing party, and they had a race on board. In fact, they had lots of parties; every night there was entertainment of some kind, which was interesting. [Laughter] That was the first time I actually tasted English beer, which is bitter. I thought it was a terrible taste; I couldn’t imagine why people liked the stuff. [Laughter]

When we got to England, there was a certain amount of hassle with customs, but everything turned out to be okay. My stay at Oxford University was also interesting because there was a lot of chance to communicate and work with people from Christendom. They were soaked in Christianity and in Englishness to the marrow of their bones, and they were still wise, which is a very mind-blowing experience. Such dignified people! Very good people there. But at the same time, you can’t ruffle their sharp edges; if you make the wrong move, you’re afraid that they are going to freeze to death or else that they’re going to strike you dead.

At Oxford, I heard lectures on comparative religion, Christian contemplation, philosophy and psychology. I had to struggle to understand those lectures. I had to study the English language: I was constantly going to evening classes organized by the city for foreign students. I was trying to study their language at the same time that I was trying to understand those talks on philosophy, which was very difficult, very challenging. The lectures were highly specialized: they didn’t build from the basic ground of anything, particularly. They presumed that you already knew the basic ground, so they just talked about certain highlights. It was very interesting and very confusing. If I was lucky, I might be able to pick up one or two points at each lecture.

I was continuing with that situation, nevertheless, but I was looking for some way to work with potential students of Buddhism. I made contact with the London Buddhist Society, which is an elderly organization more concerned with its form than with its function as Buddhists. Quite a lovable setup! Then I was invited to visit a group of people who had a community in Scotland. They asked me to teach and to give meditation instruction. It was very nice there, a fantastic place! Rolling hills, somewhat damp and cold, but beautiful. It was acceptable. I spent a long time with them, commuting back and forth between Oxford and Scotland. Finally they asked me to take over the trusteeship of their place, and offered their place as up to me to work with. The whole environment there was completely alien, completely untapped as far as I was concerned. But at the same time, there was some kind of potential for enlightenment in that world. It was very strange, a mixture of sweet and sour.

I stayed there and worked there for several years; I said goodbye to my friends and tutors in Oxford. Great people there! But I was glad to leave Oxford for a while. When I visited Oxford again, it looked much better than it had for the very reason that I didn’t have to live there. The situation in Scotland turned out to be somewhat stagnant and stuffy: there was no room for expansion except for my once-a-month visits to the Buddhist Society, which was filled with old ladies and old gentlemen. They weren’t interested in discussion, and the longest they could sit was twenty minutes. They thought that they were very heroic if they could sit for twenty minutes. We wouldn’t be able to mention anything about nyinthüns to them [laughter]; they’d completely freak out. From their point of view, being good Buddhists was like being good Anglicans-the Church of England. That problem still continues, up to the present.

At some point, I planned to make a visit to India. I thought it would be appropriate to check it out again, so to speak. I also wanted to visit His Holiness Karmapa at Rumtek. I was also invited by the queen of Bhutan, Ashi Kesang, to visit her country. She was very gracious, and also somewhat frustrated that she couldn’t speak proper Tibetan. She was hoping that her English was much better than her Tibetan, so that I could teach her in English about Buddhist practice. I tried to do so, but she was a rather lazy student and didn’t want to sit too long. But she had good intentions. She is now the royal mother of the king of Bhutan.

I took my retreat at Taktsang, which is outside of Paro, the second capital of Bhutan. Taktsang is the place where Padmasambhava meditated and manifested as Dorje Trolö. Being at Taktsang was very ordinary at first. Nothing happened; it looked just like any other mountain range. It was not particularly impressive at all, at the beginning. I didn’t get any sudden feedback, any sudden jerk at all. It was very basic and very ordinary. It was simply another part of Bhutan. Since we were guests of the queen, our needs were provided for by the local people. They brought us eggs and firewood and meat as part of their tax payment; they were very happy to give their tax payment to a holy lama. They liked to fulfill their function that way rather than give it to the administration. They were very kind and very nice, and we were provided with servants and with everything we needed.

The first few days were rather disappointing. “What is this place?” I wondered. “It’s supposed to be great; what’s happening here? Maybe this is the wrong place; maybe there is another Taktsang somewhere else, the real Taktsang.” But as I spent more time in that area-something like a week or ten days-things began to come up. The place had a very powerful nature; you had a feeling of empty-heartedness once you began to click into the atmosphere. It wasn’t a particularly full or confirming experience; you just felt very empty-hearted, as if there was nothing inside your body, as if you didn’t exist. You felt completely vacant, without feeling. As that feeling continued, you began to pick up little sharp points: the blade of the phurba, the rough edges of the vajra. You began to pick all that up. You felt that behind the whole thing there was a huge conspiracy: something was very alive.

The geko and the kunyer, the temple-keeper, asked me every morning, “Did you have a nice dream? Did you have any revelatory dreams? What do you think of this place? Did we do anything terrible to this place?” “Well,” I said, “It seems like everything is okay, thank you.”

The Kagyü tradition and the Nyingma tradition are brought together very powerfully at Taktsang; the influence of the practicing lineage is very strong there. There is a feeling at Taktsang of austerity and pride and some sense of wildness, which goes beyond the practicing lineage alone. When I started to feel that, the sadhana just came through without any problems. I definitely felt the immense presence of Dorje Trolö Karma Pakshi, and I told myself, “You must be joking. Nothing is happening here.” But still, something was coming from behind the whole thing; there was immense energy and power.

The first line of the sadhana came into my head about five days before I wrote the sadhana itself. The taking of refuge at the beginning kept coming back to my mind with a ringing sound: “Earth, water, fire and all the elements…” That passage began to come through. I decided to write it down; it took me altogether about five hours to write the whole thing. During the writing of the sadhana, I didn’t particularly have to think of the next line or what to say about the whole thing; everything just came through very simply and very naturally. I felt as if I had already memorized the whole thing. If you are in such a situation, you can’t manufacture something, but if the inspiration comes to you, you can record it.

That difference between spontaneous creation and something manufactured is connected with a little poem that I composed after the sadhana was already written. The spontaneousness was gone, but I thought that I had to say thank you. Somehow I had to write a poem for the end, so I wrote it deliberately. You can feel the difference between the rhythm and feeling of the sadhana and that of the poem, which was very deliberate. The poem is something of a platitude, but the rest of the sadhana was a spontaneous inspiration that came through me.

David Rome Reads:

In the copper-mountain cave of Taktsang,

The mandala created by the guru,

Padma’s blessing entered in my heart.

I am the happy young man from Tibet!

I see the dawn of mahamudra

And awaken into true devotion:

The guru’s smiling face is ever present.

On the pregnant dakini-tigress

Takes place the crazy-wisdom dance

Of Karma Pakshi Padmakara,

Uttering the sacred sound of HUM.

His flow of thunder-energy is impressive.

The dorje and phurba are the weapons of self-liberation:

With penetrating accuracy they pierce

Through the heart of spiritual pride.

One’s faults are so skillfully exposeda

That no mask can hide the ego

And one can no longer conceal

The antidharma which pretends to be dharma.

Through all my lives may I continue

To be the messenger of dharma

And listen to the song of the king of yanas.

May I lead the life of a bodhisattva.

VIDYADHARA: I feel that this poem has a lot of platitudes because it was just some personal acknowledgement of my own stuff.

I think that in the future people will relate with this sadhana as a source of inspiration as well as a potential way of continuing their journey. Inspiration from that point of view means awakening yourself from the deepest of deepest confusion and chaos and self-punishment; it means being able to get into a higher level and being able to celebrate within that.

Any questions?

QUESTION: Rinpoche, why do we read the sadhana at the full moon and the new moon?

VIDYADHARA: Well, the full moon is regarded as the fruition of a particular cycle in one’s state of mind. It’s like a cosmic docking, like a space ship landing. It is very conveniently worked out: that day is regarded as sacred. Most of the full moon and new moon days are also related with things the Buddha did. So the sadhana is read on that particular day because of our potential openness: we can open ourselves, we can take advantage of the gap that is taking place. It could be a freak gap or a very sane gap.

Q: Do you think that the traditional observances of ceremonies on various days of the month—I don’t mean just the full moon and the new moon, but a whole monthful and a whole yearful and a whole calendar full of liturgies—is an expression of decadence? Or do you think there is something to it?

V: Well, originally it was not an expression of decadence. Of course, it could become decadent, just like the Christian notion of Sunday, which has become just a day off. But at this point, I don’t think it’s possible. The sadhana is simply an expression of tradition, and it should be conducted properly; it depends on how you take part in it. You have two choices. For instance, you could regard the day that you get married as a sacred day or as just a social formality. It’s up to you.

Q: I guess I’m bothered by the relationship between tradition and impermanence. It seems to me that institutions and rigid traditions are the public analogies of ego clinging at an individual level. It seems like they provide the illusion of security, the same disastrous consequences within the long run that we find at the level of the individual, at the level of ego.

V: Well, that’s an interesting question. From the point of view of revolutionaries . . . socialists-

Q: Anarchists?

V: Anarchists, yes. I think one of the problems with that approach is that if there isn’t any format; there’s no freedom. Freedom has to come from structure, not necessarily in order to avoid freedom: freedom itself exists in structure. And the practices that we do in our own discipline are very light-handed practices. They have nothing to do with a particular dogma. We’re not particularly making a monument of our practice; we’re simply doing it. If we have too much freedom, that is neurotic: we could freak out much more easily. We could get confused much more easily because we have every freedom to do what we want. After that, there’s nothing left.

Q: Might that freakout be crazy wisdom?

V: Absolutely not! That’s just crazy. [Laughter]

Q: Would you talk about the mahakali principle in the sadhana?

V: The mahakali principle is simply an expression of the charnel ground: if you don’t relate with reality properly, there are going to be messages coming back to you, very simply.

Q: So the mahakali principle is just that innate energy we have all the time, which gives us messages?

V: Yes.

Q: You said that there are certain people who can write sadhanas, and I was wondering what you meant by that.

V: Well, not just anybody-not just any old hat-can write a sadhana for his girlfriend or for his boyfriend or for his teacher or for his Mercedes or for his Rolls Royce. You have to have some feeling of connection with the lineage-simply that.

Q: But there are no more specific criteria than that?

V: Well, that’s criterion enough. You have to be trained in the vajrayana discipline already; you have to have some understanding of jnanasattva and samayasattva working together. You have to understand devotion.

Q: What does it mean that Padmasambhava manifested as Dorje Trolö at Taktsang?

V: Well, you could say that you manifest as a mother when you become pregnant or when you bear a child. You have a different kind of role to play.

Q: I’ve been wanting to ask you about the topic of business mentality that keeps popping up. First of all, do you see a problem with it in the business world per se?

V: No see problem.

Q: No see problem? [Laughter]

V: The whole point is to have a vision of the totality. Then there’s no problem. If you don’t have a vision of the totality, obviously you will have problems.

Q: Usually when you talk about business mentality, it seems to be in opposition to a spirit of givingness or openness. Does that create a problem if you’re involved with businesses in the outside world?

V: I don’t think so. That’s simply part of the adornment. You have to relate with your parents and your background and your culture in any case, which is all outside of the Buddhist tradition. Doing that is very new to most of you. So you have to relate with those situations in any case. I don’t see any particular problems; those things are regarded as reference points, as the stuff we have to work with.

Q: I wonder if you think that in terms of this community and the businesses happening within it, if there might be a need for a more straightforward approach to business?

V: Sure-on the basis of the same logic that we are involved in already.

Well, friends, I think it’s time to end at this point. This seminar has been an unusual one: it is the first time that we have tried to study the sadhana. I’m very glad that nobody just came here from hearing an announcement on the radio. Everything has happened by word of mouth, on a personal basis. That gives me a lot of encouragement that we could do this more in the future. We don’t have to simply present what we are doing as newspaper announcements. An actual student-teacher relationship can take place here, which is great, fantastic.

But I don’t think you have sat enough during this seminar. I must say I’m rather disappointed in your participation in the sitting practice. However, we should try to do better next time. Last but not least, I’m glad you had a chance to learn more about the sadhana, and I hope you will be able to work on those things. We have seen that there are different levels of development within the sadhana: the charnel ground principle, devotion, generosity. All those subjects are very compact and very definite, so hopefully you will be able to work on those things. Whether you go back to your hometowns or whether you live here, please try to sit and practice. That’s the only way to understand the sadhana better.

For our closing reading I would like to read the section at the end of the sadhana, which is dedicated to all of you.

David Rome Reads:

The wisdom flame sends out a brilliant light—

May the goodness of Dorje Trolö be present!

Karma Pakshi, lord of mantra, king of insight—

May his goodness, too, be present!

Tüsum Khyenpa, the primeval buddha

Beyond all partiality-may his goodness be present!

Mikyo Dorje, lord of boundless speech—

May his goodness be present here!

Rangjung Dorje, faultless single eye of wisdom—

May his goodness be present here!

The Kagyü guru, the light of whose wisdom is a torch

For all beings-may his goodness be present!

The ocean of wish-fulfilling yidams who accomplish all actions—

May their goodness be present!

The protectors who plant firm the victorious banner