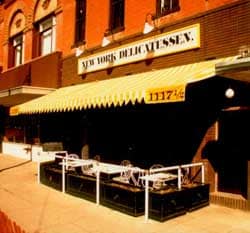

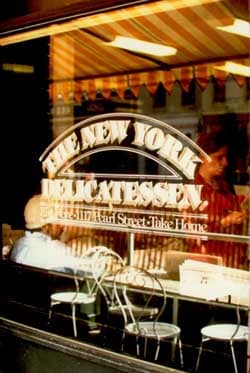

I first met the Vidyadhara and became a student when I was 20. Within a few brief years, I had lived at Tail of the Tiger (Karmê Chöling), the first live-in Maitri community, married, attended seminary, and moved to Boulder. Faced with trying to earn living expenses in a town where student-dominated minimum wage jobs ruled the economy, my wife and I decided to start a small business “so we could work part time and devote ourselves to practice”. Honestly, that is what we thought. In 1975, we came up with the brilliant idea of starting a genuine “New York-style” delicatessen – just 2,000 miles from its sources of supply.

We took a partner, and began all the necessary steps, which included hosting parties for our friends where we served the foods that our planned shop would offer. On the “grand opening day”, there were lines around the block, and many comical disasters occurred. But outwardly, our little business gave all appearances of being a smash hit. The inner story was another matter, however.

The unvarnished truth was that, as of opening day, none of the three of us had ever worked a single day in a restaurant. And that is indeed what the New York Delicatessen — on Boulder’s Pearl Street – was. Despite its tiny size, and in contrast to most true New York delis, nearly all our customers wanted to sit at our handful of tables and be served their meals by wait staff. Located right downstairs from the original Karma Dzong, we were insanely busy from morning to night every single day.

With all the chaos of trying to run the place, one area that was totally neglected was the back-office function. We had hired a fatherly “business consultant” who told us to just put all the papers floating through the tiny rear storeroom into a shoe box, and he would take care of it all. He even brought the shoebox. This included timecards, receipts for delivery of bulk food, shipping notices, restaurant guest checks, deposit slips, tax receipt forms, “petty cash” slips, and who knows what else. Relieved to not have to handle the burden of this morass of details on top of the demands of keeping the hordes of customers happy, we eagerly did what he said. His advice was “just keep the customers marching through the place, and everything is going to be just fine.”

The problem was that everything wasn’t fine. True, we had no shortage of customers, but as the first few days turned to weeks, we experienced a mystifying but intensifying shortage of money. With each week, there seemed to be less and less. The bills were falling behind, and we seemed to have to rush the day’s receipts to the bank to make payroll or cover the checks that had been written the day before. The illusion of our success stood in marked contrast to our private experience, which was that of being in a tightening noose. Our consultant’s advice was to just “stay the course”.

With discomfort rapidly unfolding into full-blown crisis, it was time to seek the advice of the Vidyadhara. Of course, by then, our minds had been swallowed by ambition, the endless work demands, and sheer terror. Our intention to devote ourselves to practice had been thoroughly annihilated. Nevertheless, he was very kind.

We poured out our dilemma: while the streams of customers day and night were our masters, we were drowning financially. Having put large sums of our families’ money at extreme risk, we were in panic, completely exhausted and strung out, and thoroughly trapped.

He listened patiently. When we had fully poured out our tale of woe, he paused, breathed, cleared his throat and in a quiet voice offered us some advice.

As best as I can recall, this is what he said:

“When you take a leap into the phenomenal world, you may think it is a very bold and heroic thing to do. However, you might awake, as if from a dream, and find yourself in the mouth of a crocodile.”

The accuracy of this description took my breath away. He had described in stark precision exactly what we had done and were experiencing, and reflected appalling contrast between our projections and reality.

“Yes, that’s exactly it, that’s right . . . but what do we do now?” was the obvious question.

“When you are in the crocodile’s mouth, you have to carefully examine every tooth.”

This was indescribably disheartening while at the same moment, totally penetrating. There was to be no rescue, no “magic bullet”, no hero charging in on a white horse. Yet, his advice was utterly on target, beyond speculation, debate or second thought.

I knew what I had to do, which was to go right into the heart of the cesspool of confusion we had been trying to avoid. I asked my partners if they would cover my shifts at the shop for the upcoming weekend. This was an outrageous demand because it was so busy and the hours were brutal. But while they did, I got every piece of paper back from our “consultant” — he had not yet prepared a single financial statement – and emptied the shoebox.

I took them home, spread them out on the living room floor, and spent the next three days and nights processing every bit of information they contained. I occasionally called the restaurant with instructions such as “order one pastrami sandwich from each of our countermen, take it in the back, take it apart and weigh the pastrami.”

When that weekend was done, I had a rather complete financial model of our business. There hadn’t been any theft or major loss. We were suffering the death of a thousand slices – we were going broke a nickel at a time.

Every time four and three-quarter ounces of pastrami (instead of four) went out between the slices of bread, every time a glass was dropped and broken, every time a server worked an hour when there was slack time, every time we sent someone to the supermarket because some ingredient ran out, another tiny sum of money flowed out rather than in. We needed to learn exactly how many useable slices of bread we could get out of a loaf – the ends didn’t count. And of course, driven by the urge to ingratiate ourselves to our customers, our prices were just a little too low.

So we adjusted all those things as best we could and fired the business consultant. Gradually the business finances stopped leaking, and the ship began to float rather than sink. But we realized that our physical layout was horribly inefficient for the sit-down restaurant that our customers wanted. So instead of beginning to pay back our huge family debt, we felt we had no choice but to go even deeper into debt, to totally rebuild our business or it would never flourish.

In 1977, Boulder built the Pearl Street Mall, and there would be a two-week gap when our block was closed for heavy construction. We made the near suicidal decision to close for 17 days, and in that time totally rebuild our business. At the edge of financial ruin, we somehow found angel designers and contractors who believed in us enough to go along with the plan.

When it was done and reopened, we had untied the worst of our logistical knots, and our business began to flourish. That year we hosted His Holiness the XVIth Karmapa and his entourage for bowls of our signature matzoh ball soup. We managed to go forward to experience a rich weave of success and failure over the following years.

Looking back over thirty years, the single moment in which the Vidyadhara described where we were and what to do stands out as the pivot point of the whole thing. In how I approached business and livelihood, that advice has lit the way again and again.

***

FRIDAY, JUNE 22, 2007

It’s 4:00 Am and I find Mother’s Milk an engaging topic for discussion.

The first dream I ever had about the Vidyadhara was about Mother’s Milk. In this vivid dream circa early 1980’s while I was still a student at Naropa, I had a dream that I was at a fancy party with many people milling about in a Great Room. I was in the kitchen looking into this room of elegantly dressed people but feeling somewhat intimidated, out of place and impoverished. Then, the Vidyadhara entered the kitchen where I was standing alone only he was young, very young like a schoolboy in shorts. He went right to the refrigerator where he grabbed a bottle of milk drinking from it directly. When he finished, he turned to me and handed me the bottle of milk saying, “Here, this is for you.”

That was really my experience of the mandala at that time in my life–one of Mother’s milk–very nurturing, generous and kind. Later when I worked at Naropa for years with very little pay, it didn’t really matter because there was so much richness. To be introduced to a culture where wealth is a kind of transcendent state of mind is remarkable. It transformed my life. I greatly admired Trungpa Rinpoche’s organizational acumen and his insistence on elbow grease as the basis for true wealth–the idea that green was not only money itself but the effort one brought to projects. To me there was some kind of magic in making things happen out of nothing. To this day, everything I do administratively is infused with his inspiration.

Jacqueline Gens Brattleboro, VT

***

CTR on money

On the whole, we should regard money as mother’s milk: it nourishes us and it nourishes others. That should be our attitude to money. It’s not just a bank coupon that we have in our wallet. Each dollar contains a lot of past; many people worked for that particular one dollar, one cent. They worked so hard, with their sweat and tears. So it’s like mother’s milk. But at the same time, mother’s milk can be given away and we can produce more mother’s milk. So I wouldn’t hang on to it too tightly. -CTR, 19 June 1981.

Excerpted from a talk to the Ratna Society. (c)2007 by Diana J. Mukpo. Used here with her permission.

ALAN SCHWARTZ